| Citation: | Wenjing Ding, Youchuan Li, Lan Lei, Li Li, Shuchun Yang, Yongcai Yang, Dujie Hou. Biomarkers reveal the terrigenous organic matter enrichment in the late Oligocene−early Miocene marine shales in the Ying-Qiong Basin, South China Sea[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(3): 31-53. doi: 10.1007/s13131-022-2081-6 |

There was a gradual warming since about 25.5 Ma on the earth which caused the melting of the permanent ice sheets in Antarctica and the Northern Hemisphere, as mainly evidenced by the negative excursion of marine benthic foraminiferal δ18O records (Zachos et al., 2001). The period during late Oligocene−early Miocene in the South China Sea witnessed an increase of the East Asian monsoon intensity which caused the warming and more humid climate (Wan et al., 2007, 2010; Ding et al., 2021). Hence, the East Asian climate has been characterized as having a distinctive difference of desertification in Asian interior predominately influenced by the East Asian winter monsoon, and the humid monsoonal region under the influence of abundant annual precipitation brought by the East Asian summer monsoon in southern China and the southern China Sea (Fig. 1b) (Guo et al., 2002; Sun and Wang, 2005; Qiao et al., 2006; Spicer et al., 2014; Clift et al., 2015; Song et al., 2018).

Higher plant-derived biomarkers including some sesquiterpenoids, diterpenoids, and triterpenoids, and their derivatives are biologically informative molecules that can be used to indicate certain types of plants. For example, diterpenoids and related aromatic compounds originate from gymnosperms (Otto et al., 1997; Hautevelle et al., 2006). Triterpenes with oleanane-, ursane- and lupane-type skeletons, and their derivatives in aliphatic and aromatic fractions, are derived from various precursors including β-amyrin that can be synthesised by almost all angiosperms (Grantham et al., 1983; Ten Haven and Rullkötter, 1988; Murray et al., 1997). Bicadinanes are derived from polycadinene, a resinous polymer produced by tropical/sub-tropical angiosperms such as the Dipterocarpaceae (Van Aarssen et al., 1992; Murray et al., 1997; Nytoft et al., 2010). Variations of relative abundance variations of these higher plant-derived compounds and climate variations over geological time are particularly relevant in those areas where the flux of terrigenous organic matter to the marine environment is high (Hinrichs and Rullkötter, 1997b; Edwards et al., 2004; Cesar and Grice, 2019). For example, the oleanane index (oleanane/C30 αβ hopane) and the angiosperm/gymnosperm index (AGI)1) were measured in aliphatic hydrocarbon fractions (Killops et al., 1995; Nakamura et al., 2010), and were used to characterize the variation of angiosperm plants and gymnosperms in floral composition, and then to infer coeval the regional or even the global climate change during geological periods.

Terrigenous organic matter enrichment in high-quality marine source rocks is mainly influenced by the large influx of terrigenously-dominated organic matter due to a dominance of higher plant materials provided by large rivers and deltas, in many sedimentary basins, including the Amazon fan (Boot et al., 2006; Van Soelen et al., 2017), the Niger Delta (Samuel et al., 2009; Akinlua and Torto, 2011), the Gulf of Mexico (Goñi et al., 1997; Waterson and Canuel, 2008), the northern and northwestern South China Sea (Zhang et al., 2014, 2019; Liu et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2021, 2022a; Wang et al., 2021b), the East China Sea Basin (Wang et al., 2021a), and some parts in the deep-sea sediments (Holtvoeth et al., 2001; Mignard et al., 2017). In addition, sea level changes, redox conditions, terrigenous supply mainly influenced by the regional tectonic uplift and strengthened physical erosion of the source area likely exert a control on the terrigenous organic matter enrichment in the marine environment (Li et al., 2006; Huang and Tian, 2012; Mignard et al., 2017; Van Soelen et al., 2017; Jiwarungrueangkul et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Previous study in Liu et al. (2016) suggested that the formation of fluvial sediments in surrounding drainage systems in the South China Sea was controlled principally by the East Asian monsoonal climate with warm temperature with high precipitation and subordinately by tectonic activity and specific lithological characteristics. Specifically, the East Asian monsoonal climate which was dominated by the summer monsoon in the South China Sea brought extra annual precipitation, which intensified the physical erosion of the drainage source area in the warm and humid condition (Wang et al., 1999; Clift et al., 2002, 2014; Wan et al., 2007, 2010; Hu et al., 2012). This process also results in larger flux of terrigenous organic matter along with the fluvial clastic debris mainly through the river-delta system to the lower continental slope in the South China Sea (Huang et al., 2016b; Jiwarungrueangkul et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b). For the influx of the terrigenous organic matter, there are mainly two main process of terrigenous organic matter transportation from the continent to the ocean: river discharge and eolian dust export (Dahl et al., 2005; Mignard et al., 2017; Jiwarungrueangkul et al., 2019), in which most of the terrigenous organic matter at low latitudes like the South China Sea were mainly transported to the oceans through the river discharge (Zhao et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021b). However, the enrichment of the terrigenously-dominated organic matter during the warmer and humid early Miocene and the middle Miocene in the South China Sea were not deeply investigated. Additionally, the controlling factors of terrigenous organic matter in the marginal marine environment of the northwestern South China Sea and the influence of the East Asian monsoonal climate on the terrigenous organic matter enrichment remains obscure.

In this study, in addition to the bulk organic geochemistry study on the large quantity of the late Oligocene−early Miocene shales in the Ying-Qiong Basin, more specific plant biomarkers than in previous studies were tentatively analyzed to trace the variation of the plant types in flora and climate change during the corresponding geological interval. Correlations between the organic matter enrichment in shales and sedimentary environments of organic matter, variations of plants in flora, climate and regional tectonic movements were conducted to analyze the controlling factors of terrigenous organic matter enrichment in the northestern South China Sea. This work will be beneficial for understanding the development of high-quality terrigenously-dominated marine source rocks in the northern South China Sea.

The Ying-Qiong Basin includes the Yinggehai Basin and the Qiongdongnan Basin, which is located in the northeastern continental shelf of the South China Sea (Figs 1a and b). Sedimentary strata of the Ying-Qiong Basin consist of the Eocene Lingtou Formation, the Oligocene Yacheng and Lingshui formations, the Miocene Sanya, Meishan and the Huangliu formations, and the Pliocene Yinggehai Formation. For a detailed description of the stratigraphy and structural movements of the study area, refer to Ding et al. (2021).

Source rocks in the Qiongdongnan Basin are mainly terrigenously-dominated shales in the Oligocene Yacheng and Lingshui formations, with their vitrinite reflectance (Ro)>0.6% (Huang et al., 2003; Ding et al., 2018, 2021; Wu et al., 2018; Zhang and Feng, 2021). The Eocene lacustrine Lingtou Formation, to our knowledge, was only drilled in one new well in the Songtao low uplift during the year 2022. Coal-bearing source rocks with high terrigenous organic matter content were mainly found the Yacheng Formation in the Ya’nan and Yabei sags (Huang et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2003; Xiao et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2021). Shales in the shallower upper Yacheng-Lingshui-Sanya-Meishan formations were mainly deposited in littoral to neritic faces in the Qiongdongnan Basin (Ding et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2021). In the neighboring Yinggehai Basin, source rocks characterized by a dominance of Type III-II2 organic matter in hydrocarbon generation window include shales in the Sanya and Meishan formations (Huang et al., 2003, 2005; Zhang et al., 2021), which were mainly deposited in littoral to neritic environment (Ding et al., 2021, 2022b; Fan et al., 2021). Shales in the deeper buried Oligocene Yacheng-Lingshui formations were not drilled in the Yinggehai Basin, which were thought as not the major source rocks due to that they were not well-developed in this basin (Huang et al., 2005, 2009).

The age controls of the sedimentary rocks were confirmed using the nannofossil biostratigraphy, including the records of calcareous nannofossils and planktonic foraminifers, which were obtained from samples in many wells drilled by the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) in the Ying-Qiong Basin. The detailed ages of each formation refer to the age-depth model of the late Oligocene-Miocene sedimentary rocks in the Ying-Qiong Basin in Ding et al. (2021). Specifically, the formation interfaces and their ages in the Ying-Qiong Basin are: T80−T70 (36.0−28.4 Ma, the Yacheng Formation), T70−T62 (28.4−25.5 Ma, the lower Lingshui Formation), T62−T61 (25.5−23.8 Ma, the middle Lingshui Formation), T61−T60 (23.8−23.0 Ma, the upper Lingshui Formation), T60−T51 (23.0−18.3 Ma, the lower Sanya Formation), T51−T50 (18.3−16.0 Ma, the upper Sanya Formation), T50−T41 (16.0−13.4 Ma, the lower Meishan Formation), T41−T40 (13.4−10.5 Ma, the upper Meishan Formation), T40−T31 (10.5−8.2 Ma, the lower Huangliu Formation), T31−T30 (8.2−5.3 Ma, the upper Huangliu Formation).

In the late Oligocene−middle Miocene strata of the Qiongdongnan Basin, Rock-Eval pyrolysis and TOC measurement were conducted in 103 shales samples in Well Y7-4 (the Ya’nan Sag), 86 shale samples in Well L2-1 (the Lingshui Sag), 49 shales in Well S36-1 and 44 shales in Well S24-1 (the Songnan Sag), 53 shales in Well B19-2 and 61 shale samples in Well B20-1 (the Baodao Sag). In the Yinggehai Basin, 28 cuttings from Well H29-1 were collected for total organic carbon analyses. Two sidewall cores and 8 cutting samples from Well H29-1 in the Yinggehai Basin, 19 cutting samples from Well B19-2 and 9 cutting samples from Well S29-1 in the Qiongdongnan Basin were collected for aliphatic biomarker analyses. The location of each well was shown in Fig. 1c.

A summary of parameters including the data ranges, average values and sample amounts of the measured total organic carbons (TOC), vitrinite reflectance (Ro) and pyrolysis data are concluded in Table 1. All the original data of the shale samples from these 7 wells are included in Supplementary Table S1.

| Formation | TOC/% | Ro/% | Tmax/°C | S1 rock/(mg·g−1) | S2 rock/(mg·g−1) | S1+S2 rock/(mg·g−1) | HI TOC/(mg·g−1) |

| Upper Meishan | 0.32−0.78 | 0.42−0.63 | 412−427 | 0.01−0.56 | 0.16−3.21 | 0.17−3.37 | 55−428 |

| 0.44 (20) | 0.52 (6) | 422 (22) | 0.09 (22) | 1.01 (22) | 1.10 (22) | 177 (22) | |

| Lower Meishan | 0.07−0.33 | 0.35−0.65 | 406−432 | 0−0.29 | 0.02−4.17 | 0.02−4.33 | 8−479 |

| 0.33 (50) | 0.53 (11) | 416 (39) | 0.04 (49) | 0.37 (49) | 0.40 (49) | 81 (49) | |

| Upper Sanya | 0.08−1.09 | 0.37−0.67 | 412−435 | 0−0.32 | 0.04−3.37 | 0.04−3.60 | 10−396 |

| 0.46 (77) | 0.58 (22) | 425 (76) | 0.07 (77) | 1.33 (77) | 1.42 (77) | 180 (62) | |

| Lower Sanya | 0.18−2.9 | 0.39−0.95 | 403−447 | 0−0.65 | 0.07−6.41 | 0.07−7.01 | 18−434 |

| 0.72 (81) | 0.62 (27) | 430 (74) | 0.15 (75) | 1.41 (75) | 1.55 (75) | 132 (37) | |

| Upper Lingshui | 0.14−2.40 | 0.61−0.74 | 407−450 | 0.01−0.67 | 0.02−5.10 | 0.06−5.77 | 11−226 |

| 0.67 (38) | 0.66 (8) | 427 (32) | 0.15 (38) | 0.94 (38) | 1.10 (38) | 97 (38) | |

| Middle Lingshui | 0.11−1.37 | 0.63−0.86 | 420−441 | 0−1.13 | 0.02−2.64 | 0.03−2.89 | 10−313 |

| 0.51 (72) | 0.72 (16) | 428 (33) | 0.16 (62) | 0.68 (62) | 0.84 (62) | 102 (62) | |

| Lower Lingshui | 0.16−2.02 | 0.72−0.88 | 425−445 | 0.01−0.41 | 0.09−2.42 | 0.10−2.67 | 9−310 |

| 0.51 (45) | 0.77 (10) | 432 (29) | 0.12 (41) | 0.77 (41) | 0.89 (41) | 138 (41) | |

| Upper Yacheng | 0.28−0.78 | 0.84−1.05 | 422−453 | 0−0.12 | 0.21−0.69 | 0.25−0.81 | 58−100 |

| 0.46 (19) | 0.95 (7) | 439 (8) | 0.07 (8) | 0.39 (8) | 0.46 (8) | 74 (8) | |

| Note: In a−b, a and b are minimum and maximum values, respectively; in c ( d ), c is the average value, and d is the sample numbers. All the original data of the shale samples from these seven wells are shown in Supplementary Table S1. | |||||||

After rinsing with deionized water and menthol to remove the possible surficial contamination, the angular-shaped cuttings and sidewall cores were powdered into 200 mesh for Rock-Eval pyrolysis and TOC analysis. Rock-Eval pyrolysis was conducted on a Rock-Eval VI to measure the amounts of free hydrocarbons (S1), potential hydrocarbons (S2) and the temperature of maximum generation (Tmax). The TOC was measured on a Leco CS344 analyser, after the samples were preprocessed with 5% dilute hydrochloric acid for 12 hours to remove the carbonate minerals and then were rinsed with deionised water more than 50 times to completely remove residual hydrochloric acid.

Samples were crushed and added with 10% hydrochloric acid to eliminate carbonates and 40% hydrofluoric acid to eliminate silicates. The extracted kerogen were embedded in liquid epoxy resin, polished to a smooth surface, and desiccated for 12 h. Ro was measured using a Leica MPV-SP microphotometer under an oil-immersion objective lens that was calibrated using a double calibration method using two Ro standards. The samples were re-measured if the measurement deviation of the standard samples was greater than ±0.02%. The statistic median value among 35−50 countered data was recorded for each sample, with the average Ro reported in Supplementary Table S1.

The rinsed and powdered shale samples were solvent extracted using dichloromethane in a Soxhlet apparatus for 72 h. Asphaltenes in the extractable organic matter were precipitated using excess n-hexane to leave the soluble maltenes. The maltenes were separated by column chromatography into aliphatic hydrocarbons (elution with n-hexane) and aromatic hydrocarbons (eluted with n-hexane: dichloromethane, 1:2, v:v). The aliphatic hydrocarbons were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) on an Agilent 6890 GC interfaced to an Agilent 5973 mass selective detector (ionisation source operated at an electron impact energy of 70 eV). An HP-5MS fused silica capillary column was used (30 m×0.25 mm, film thicknesses 0.25 μm). The oven temperature was programmed to start at 20℃ (hold for 1 min), increased to 100℃ at 20℃/min, and from 100℃ to 310℃ at 3℃/min, with a final hold of 18 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The aromatic hydrocarbons were not analyzed by GC-MS due to the contamination of some shale samples.

In the Qiongdongnan Basin, the deeper buried shales in the upper Yacheng Formation mostly have higher Tmax (422−453℃; average 439℃) and lower hydrocarbons index (HI; 58−100 mg/g TOC; average 74 mg/g TOC) than other formations (Table 1). Shales in the lower Lingshui Formation have Tmax ranging from 425−445℃ (average 432℃), S1+S2 in the range of 0.10−2.67 mg/g rock (average 0.89 mg/g rock), and HI of 9−310 mg/g TOC (average 138 mg/g TOC). The middle Lingshui Formation shales have very close ranges of Tmax (420−441℃; average 428℃), S1+S2 (0.10−2.67; average 0.89 mg/g rock) and HI (10−313 mg/g TOC; average 102 mg/g TOC) with the lower Lingshui Formation shales. Pyrolysis data of shales in the upper Lingshui Formation are characterized by S1+S2 in the range of 0.06−5.77 mg/g rock (average 1.10 mg/g rock) and HI of 11−226 mg/g TOC (average 97 mg/g TOC). It is noticeable that there are higher average values of S2 in shales of the upper and lower Sanya formations than other formations (0.37−1.01 mg/g rock), in which the lower Sanya Formation shales have average S2 of 1.41 mg/g rock and the upper Sanya Formation shales have average S2 of 1.33 mg/g rock. The lower Meishan Formation shales have slightly lower average values of the above pyrolysis parameters, with average Tmax of 416℃, average S1+S2 of 0.40 mg/g rock, average HI of 81 mg/g TOC, compared to the upper Meishan Formation. The upper Meishan Formation has Tmax values in the range of 412−427℃ (average 422℃), S1+S2 ranging from 0.17−3.37 mg/g rock (average 1.10 mg/g rock) and HI in the range of 55−428 mg/g TOC (average 177 mg/g TOC).

The vitrinite reflectance (Ro) of shales in the Meishan Formation ranges from 0.35%−0.65% (average 0.53%; Table 1), indicating that the Meishan Formation shales are mostly under low maturity stage. Most shales in the lower Sanya Formation are buried deeper than the oil window, due to their generally higher Ro (0.39%−0.95%; average 0.62%) than the upper Sanya Formation (0.37%−0.67%; average 0.58%). Shales in the deeper buried strata which are the upper Yacheng-Lingshui formations have higher thermal maturity than the shallower Sanya-Meishan formations, with Ro in the range of 0.61%−1.05%.

Shales in the upper Yacheng Formation and some shale samples in the Lingshui-Sanya-Meishan formations are in poor to fair quality (Fig. 2), which is almost consistent with previous study in Ding et al. (2021). However, a dominance of shales from middle Lingshui-Sanya formations was plotted in good-excellent source rock quality area. In the seven wells in various sags of the Qiongdongnan Basin, it is concluded that shales in the middle Lingshui Formation and upper Lingshui-Sanya formations have better source rock quality than in other formations (Figs 2c-h). For example, some shales in the middle to upper Lingshui formations and lower Sanya Formation have excellent quality in the Songtao low uplift (Figs 2b, c). Some shales in the above formations are characterized by good to excellent quality in Well B19-2 of the Baodao Sag (Fig. 2g) and in Well Y7-4 of the Ya’nan Sag (Fig. 2h). Organic matter of the shales are mainly Type III−II2, and only some shale samples in the Lingshui-Sanya-Meishan formations are interpreted to contain Type II1 kerogen (Fig. 2b).

n-Alkanes detected in the samples are mostly in the range of nC15 to nC38, due to partial evaporative loss of low molecular weight n-alkanes (carbon number<15) during speration (Ahmed and George, 2004). There are varying distribution patterns of n-alkanes in shales in different formations (Fig. 3). For example, in Well B19-2 of the Qiongdongnan Basin, shales in the lower-middle Lingshui Formation have a unimodal profile of n-alkanes with maxima at nC20. The representative samples in the upper Lingshui Formation sample (3 460 m) and lower Sanya Formation (3 100 m) have the unimodal n-alkane distribution with maximum at nC27 and nC29, respectively. In contrast, the shallower upper Sanya Formation shale sample (2 748 m) has a bimodal n-alkane distribution with odd-over-even predominance, maximized at nC19 and nC29 (Fig. 3). In Well H29-1 of the Yinggehai Basin, n-alkanes of shales in the lower part of the Sanya Formation (3 578 m and 3 562 m) are characterized by a bimodal distribution with a maximum at nC19/nC20 or nC29/nC31, while shales in the upper part of the Sanya Formation (3 528 m) and the lower Meishan Formation have a similar unimodal distribution with a maximum at nC19 or nC20. In addition, two fine sandstone samples in the lower part of the Sanya Formation have a dominance of high molecular weight n-alkanes (the maximumed peak at nC29 or nC31) in n-alkane distributions, which indicates the possible origin of the deeper buried source rocks in lower Sanya Formation and/or older strata which have high abundance of terrigenous organic matter.

The terrestrial/aquatic ratio (TAR) from Bourbonniere and Meyers (1996) in shales of the Sanya Formation ranges from 0.93−8.15 (average 3.00), which are mostly higher than in other formations (0.59−3.84; average 1.73). Similarly, the average chain length of long-chain n-alkanes (ACL), which was defined as (25×nC25+27×nC27+29×nC29+31×nC31+33×nC33)/(nC25+nC27+nC29+nC31+nC33) (Baas et al., 2000; Nott et al., 2000), has the range of 27.78−28.90 (average 28.42), and is mostly highly than the deeper buried Linghui Formation (26.86−28.21; average 27.51; Table 2). The shallower Meishan Formation shales have ACL ranging from 27.5−28.94 with an average of 28.24. The Paq index was defined as (nC23+nC25)/(nC23+nC25+nC29+nC31) (Ficken et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2005; Nichols et al., 2014), and it ranges from 0.35 to 0.78 (average 0.58). The carbon preference index (CPI22-32) is mostly higher than 1.0 (0.86−1.71; average 1.15).

| Well name | Depth/m | Formation | Lithology | Sample type | TAR | ACL | Paq | (nC31/(nC27+ nC29+nC31) | CPI | Pr/Ph | Pr/nC17 | Ph/nC18 | C19 TT/(C19 TT+C23 TT) | des-A-oleanane/C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | */C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | X/C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | Y/C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | Z/C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane |

| H29-1 | 3 038−3 040 | lower Meishan | shale | cuttings | 0.76 | 28.01 | 0.65 | 0.26 | 1.14 | 2.33 | 2.25 | 0.72 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| H29-1 | 3 088−3 094 | lower Meishan | shale | cuttings | 0.69 | 27.85 | 0.66 | 0.24 | 1.22 | 2.28 | 2.37 | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| H29-1 | 3 528 | Sanya | shale | cuttings | 0.93 | 27.78 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 2.69 | 1.48 | 0.48 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| H29-1 | 3 562 | Sanya | shale | cuttings | 1.57 | 28.53 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 1.06 | 2.40 | 1.38 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| H29-1 | 3 578 | Sanya | shale | cuttings | 1.25 | 28.19 | 0.56 | 0.32 | 1.03 | 2.17 | 1.38 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| H29-1 | 3 580−3 582 | Sanya | shale | cuttings | 1.12 | 28.14 | 0.58 | 0.28 | 1.10 | 2.48 | 1.43 | 0.53 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| H29-1 | 3 586 | Sanya | shale | cuttings | 0.92 | 28.23 | 0.57 | 0.29 | 1.02 | 2.38 | 1.09 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| H29-1 | 3 588−3 590 | Sanya | shale | cuttings | 1.24 | 28.20 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 1.08 | 2.44 | 1.44 | 0.48 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| H29-1 | 3 593 | Sanya | fine sandstone | sidewall core | 6.01 | 28.60 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 1.06 | 1.64 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| H29-1 | 3 595 | Sanya | fine sandstone | sidewall core | 6.86 | 29.08 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 1.07 | 2.18 | 0.72 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| B19-2 | 2 350 | lower Meishan | shale | cuttings | 1.02 | 27.50 | 0.61 | 0.18 | 0.86 | 1.69 | 3.69 | 1.33 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| B19-2 | 2 748 | upper Sanya | shale | cuttings | 2.16 | 28.74 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 2.92 | 4.05 | 1.11 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| B19-2 | 2 880 | lower Sanya | shale | cuttings | 5.71 | 28.87 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.94 | 4.64 | 6.98 | 1.22 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| B19-2 | 3 100 | lower Sanya | shale | cuttings | 8.15 | 28.69 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.97 | 4.79 | 7.36 | 1.31 | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| B19-2 | 3 238 | lower Sanya | shale | cuttings | 4.52 | 28.30 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 1.09 | 4.04 | 6.59 | 1.22 | 0.62 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| B19-2 | 3 300 | lower Sanya | shale | cuttings | 4.14 | 28.34 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 1.10 | 4.37 | 5.33 | 1.01 | 0.65 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| B19-2 | 3 380 | lower Sanya | shale | cuttings | 2.87 | 28.19 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 1.10 | 3.67 | 3.49 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| B19-2 | 3 460 | upper Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 3.84 | 28.21 | 0.50 | 0.26 | 1.13 | 3.97 | 4.61 | 0.91 | 0.57 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| B19-2 | 3 878 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.89 | 27.74 | 0.62 | 0.21 | 1.25 | 4.54 | 1.94 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| B19-2 | 3 980 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 2.14 | 27.89 | 0.61 | 0.22 | 1.12 | 2.53 | 1.07 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| B19-2 | 4 020 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 2.44 | 27.88 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 1.19 | 3.49 | 3.27 | 0.66 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| B19-2 | 4 092 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.11 | 27.40 | 0.71 | 0.18 | 1.22 | 3.34 | 0.95 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| B19-2 | 4 182 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.25 | 27.40 | 0.71 | 0.19 | 1.32 | 2.35 | 1.61 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| B19-2 | 4 220 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.74 | 27.25 | 0.71 | 0.17 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| B19-2 | 4 330 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.77 | 26.91 | 0.76 | 0.07 | 1.71 | 1.47 | 2.70 | 0.63 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| B19-2 | 4 394 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.41 | 27.65 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 1.08 | 0.56 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| B19-2 | 4 510 | lower Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 0.71 | 26.93 | 0.74 | 0.06 | 1.13 | 1.26 | 1.25 | 0.64 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| B19-2 | 4 718 | lower Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 0.59 | 26.87 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 1.09 | 0.99 | 1.45 | 0.79 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| B19-2 | 4 810 | lower Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 0.72 | 26.86 | 0.76 | 0.07 | 1.67 | 1.85 | 2.06 | 0.96 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| S29-2 | 2 215 | upper Meishan | shale | cuttings | 2.25 | 28.94 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 1.28 | 2.00 | 2.63 | 0.96 | 0.11 | 0.04 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 2 535−3 555 | lower Meishan | shale | cuttings | 2.25 | 28.75 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 1.23 | 2.01 | 2.54 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 0.07 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 2 658−2 662 | upper Sanya | shale | cuttings | 1.26 | 28.55 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 1.32 | 2.16 | 2.59 | 0.92 | 0.20 | 0.02 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 2 934−2 936 | upper Sanya | shale | cuttings | 3.06 | 28.90 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 1.41 | 3.29 | 3.68 | 0.94 | 0.25 | 0.08 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 3 286−3 288 | lower Sanya | shale | cuttings | 3.75 | 28.48 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 1.20 | 3.69 | 3.78 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.11 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 3 336−3 338 | lower Sanya | shale | cuttings | 5.34 | 28.54 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 1.22 | 3.66 | 4.20 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.10 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 3 832−3 834 | upper Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.17 | 27.82 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 1.12 | 4.44 | 1.90 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.16 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 3 942−3 944 | upper Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.25 | 27.60 | 0.66 | 0.20 | 1.07 | 4.31 | 1.38 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.11 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 4 020−4 022 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 1.80 | 27.83 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 1.11 | 3.97 | 1.30 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.16 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 4 050 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 3.21 | 27.61 | 0.65 | 0.21 | 1.11 | 1.98 | 1.65 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.02 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| S29-2 | 4 158 | middle Lingshui | shale | cuttings | 3.34 | 27.81 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 1.14 | 1.83 | 1.43 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.01 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Well name | Z1/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | Ts/ (Ts+Tm) | C31 $\alpha \beta $ hopane 20S/ (20S+20R) | oleanane/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | 19$\alpha $(H)- taraxastane/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | I/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | II/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | III/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | (III+II+ I)/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | W/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | T/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | T1/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ opane | R/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ opane | (W+T+T1+R)/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | (des-A-oleanane+ *+X+Y+Z+Z1+I+ II+III+W+T+T1+R)/ C30 $\alpha \beta $ hopane | C27/C29 $\alpha \alpha \alpha $ 20R steranes | C29/C27 $\alpha \alpha \alpha $ 20R steranes | C29 20S/(20S+20R) steranes |

| H29-1 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 1.39 | 0.35 |

| H29-1 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.86 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 1.48 | 0.39 |

| H29-1 | 0.06 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.77 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 1.71 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 0.49 |

| H29-1 | 0.08 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 1.59 | 0.20 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1.98 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 3.26 | 4.04 | 0.96 | 1.04 | 0.45 |

| H29-1 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 1.03 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 1.27 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 2.11 | 2.71 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 0.44 |

| H29-1 | 0.04 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.76 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 1.25 | 1.56 | 0.49 | 2.03 | 0.50 |

| H29-1 | 0.05 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 1.12 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.60 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 1.09 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 1.80 | 2.47 | 1.13 | 0.88 | 0.48 |

| H29-1 | 0.05 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 1.05 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 1.14 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 1.91 | 2.39 | 0.63 | 1.59 | 0.42 |

| H29-1 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 3.05 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.71 | 1.53 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 3.27 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 5.23 | 6.44 | 0.50 | 1.99 | 0.51 |

| H29-1 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 2.43 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.73 | 1.36 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 2.72 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 4.29 | 5.15 | 0.66 | 1.53 | 0.49 |

| B19-2 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 1.27 | 0.12 |

| B19-2 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 1.43 | 0.34 |

| B19-2 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 2.38 | 0.29 |

| B19-2 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.10 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.41 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 2.08 | 0.35 |

| B19-2 | 0.07 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.65 | 1.19 | 0.47 | 2.13 | 0.38 |

| B19-2 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 1.11 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 1.78 | 2.32 | 0.45 | 2.22 | 0.39 |

| B19-2 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 1.23 | 0.38 |

| B19-2 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.91 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 1.50 | 2.09 | 0.67 | 1.49 | 0.44 |

| B19-2 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 3.89 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 6.45 | 6.88 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.46 |

| B19-2 | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.81 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 1.38 | 1.48 | 0.81 | 1.23 | 0.41 |

| B19-2 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 2.25 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 3.66 | 4.11 | 0.96 | 1.04 | 0.44 |

| B19-2 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 1.08 | 0.93 | 0.33 |

| B19-2 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.51 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.19 | 0.38 |

| B19-2 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 1.37 | 0.39 |

| B19-2 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 0.40 |

| B19-2 | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 1.18 | 0.40 |

| B19-2 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.75 | 1.33 | 0.56 |

| B19-2 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 0.82 | 1.22 | 0.37 |

| B19-2 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.57 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.83 | 1.20 | 0.38 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.10 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | nd | 0.85 | 1.17 | 0.16 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.59 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.39 | nd | 0.80 | 1.26 | 0.16 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.49 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.34 | nd | 0.88 | 1.13 | 0.21 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.62 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.17 | nd | 0.53 | 1.87 | 0.35 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.42 | 0.61 | 0.58 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.10 | 0.55 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.65 | nd | 0.36 | 2.79 | 0.45 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.54 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.40 | nd | 0.33 | 2.99 | 0.45 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.39 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.71 | 2.50 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 3.21 | nd | 0.49 | 2.05 | 0.42 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.38 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.89 | 2.30 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 3.19 | nd | 0.66 | 1.53 | 0.42 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.35 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.29 | 0.90 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 1.19 | nd | 0.62 | 1.61 | 0.42 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.10 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.18 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.99 | nd | 0.55 | 1.81 | 0.43 |

| S29-2 | nd | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.08 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.10 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.45 | nd | 0.55 | 1.83 | 0.41 |

| Note: TAR=terrestrial/aquatic ratio=(nC27+nC29+nC31)/(nC15+nC17+nC19); ACL=(25×nC25+27×nC27+29×nC29+31×nC31+33×nC33)/(nC25+nC27+nC29+nC31+nC33); Paq=(nC23+nC25)/(nC23+nC25+nC29+nC31); CPI22-32=Carbon preference index, = 2×(nC23+nC25+nC27+nC29+nC31)/(nC22+nC24+nC26+nC28+nC30+nC32); Pr/Ph=pristane/phytane; C19 TT=C19 tricyclic terpane; C23TT=C23 tricyclic terpane; Compounds *, X, Y, Z, Z1 are tricyclic/tetracyclic terpanes; I, II, III are arranged oleananes; W=cis-cis-trans-bicadinane, T=trans-trans-trans-bicadinane. | ||||||||||||||||||

Isoprenoids including the pristane and phytane are abundant compounds in the analyzed samples (Fig. 3). Pristane/phytane (Pr/Ph) has relatively higher ratios in the upper Lingshui-Sanya formations (2.16−4.79; average 3.40) compared to other formations (0.99−2.35; average 1.74), except four samples in the upper part of the middle Lingshui Formation in Well B19-2 (3 878−4 092 m; 2.53−4.54; average 3.47) and one sample in the middle Lingshui Formation in Well S29-2 (4 020−4 022 m; 3.97). Pr/nC17 ranges from 0.95−7.36 (average 2.64) and Ph/nC18 has a range of 0.21−1.33 (average 0.68). The cross-plot Ph/nC18 versus Ph/nC17 (after Shanmugam (1985)) of most of the shales suggests the dominant Type Ⅲ organic matter in the oxidising environment (Fig. 4a), in which shales in the Sanya Formation, the upper and middle Lingshui formations have more contribution from the Type Ⅲ organic matter than other formations. Most of shales in the upper Lingshui-Sanya formations were formed in the terrigenously-dominated environment. Some Sanya Formation samples of Well H29-1 and some shales in middle and lower Lingshui formations of Well B19-2 are more marine-influenced source rocks that were deposited in a less oxic environment with greater algal input (Fig. 4b).

The main tricyclic terpanes (TTs; Appendix Fig. A1) and tetracyclic terpanes detected of all the shale samples are C19−C26 tricyclic terpanes, C24 tetracyclic terpane, des-A-oleanane (II) and other tricyclic terpanes tetracyclic compounds including X, Y, Z, Z1 (Fig. 5). C19 TT and C20 TT relative to C23 TT vary among different samples (Fig. 5). C19 TT/(C19 TT+C23 TT) has the range of 0.16−1.00 in the upper Lingshui-lower Sanya formations (average 0.48), and are mostly higher than in other formations (0.10−0.40; average 0.22).

In addition, 10β(H)-des-A-oleanane (des-A-oleanane; II), compounds X, *, Y, Z, Z1 were identified based on their mass spectra and their relative retention time in m/z 191 mass chromatograms (Fig. 5). Lupane and des-A-lupane were not detected in the studied samples. Des-A-oleanane elutes after C24 TT and it has a mass spectrum characterized by a base peak at m/z 191, a molecular weight of 330.3 Da, fragment ion at m/z 177.1 and m/z 315.3. The tricyclic terpanes X (III), Y (IV), and Z1 (VI) were first detected and reported in a Niger Delta oil sample by Samuel et al. (2010). X is C21 tricyclic terpane characterized by a key ion at m/z 275.2 with a molecular ion at m/z 290.2, and compound * was thought as the possible steroisomer of compound X (Samuel et al., 2010). Compound Y (V) has a C26 tricyclic structure with methylpentane substituents at C8 (Samuel et al., 2010), and it has a base peak of m/z 346.2 and fragment ion at m/z 331.3 and m/z 261.2. Des-A-oleanane and compound Z were previously reported by Woodhouse et al. (1992), in which compound Z was identified as C24 10β(H)-des-A-ursane. Compound Z in this study was tentatively identified as 10β(H)-des-A-ursane, due to the fragment ion at m/z 315.2, 245.2, a molecular ion at 330.0 Da and a base peak at m/z 191.1 in its mass spectrum (Appendix Fig. A2). However, this identification is questioned by the very lower abundance of m/z 245.2 than in previous study in Woodhouse et al. (1992). Spectrum of C27 tetracyclic terpane Z1 in this study was characterized by a molecular weight of 372.3 Da, the fragment triplet at m/z 219.1, 329.3, 357.3, which is consistent with spectrum reported by Samuel et al. (2010). The structures and mass spectra of the compounds X, Y, Z, Z1 and des-A-oleanane were shown in Appendix Fig. A1 and Appendix Fig. A2, respectively.

There are very low abundance of des-A-oleanane, *, X, Y, Z, Z1 relative to C30 αβ hopane, with des-A-oleanane/C30 αβ hopane in the range of 0.01−0.17 (average 0.08), */C30 αβ hopane of 0−0.07 (average 0.02), X/C30 αβ hopane of 0−0.10 (average 0.03), Y/C30 αβ hopane of 0−0.05 (average 0.01), Z/C30 αβ hopane of 0.01−0.06 (average 0.02), Z1/C30 αβ hopane of 0.01−0.11 (average 0.05) (Table 2).

Hopanes (VII) are derived from hopanoids that are membrane lipids in prokaryotic organisms, or diagenetic products of these lipids (Volkman, 2005). The distributions of hopanes in the studied samples are dominated by C27−C35 hopanes, in which C27−C31 hopanes are the major compounds, and homohopanes decrease steadily from C31 to C35 (Fig. 5). Ts/(Ts+Tm) ratio is widely used as a maturity indicator, but is also influenced by variable types of organic matter and depositional environmental differences (Seifert et al., 1978). In Well H29-1 in the Yinggehai Basin, shales in the Sanya Formation has Ts/(Ts+Tm) in the range of 0.55−0.64 (average 0.60), mostly higher than in the other formations (0.23−0.59; average 0.41). This is consistent with generally higher thermal maturity of shales in the Sanya Formation in the Yinggehai Basin than most of the late Oliogcene−Miocene shales in the Qiongdongnan Bain (Huang et al., 2003; Ding et al., 2021). In contrast, there is no obvious difference of another thermal maturity indicator C31 αβ hopane 22S/(22S+22R) among samples, with C31 αβ hopane 22S/(22S+22R) ranging from 0.44−0.60 (average 0.56). In addition, moderate to high abundances of C30−C34 2α-methylhopanes were detected in all the Lingshui-Meishan formation shales (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In the shale samples, compound oleanane (VIII) elutes before C30 αβ hopane, with 18α(H)-oleanane and 3β-methyl-24-nor-18β(H)-oleanane as a doublet in m/z 191 and m/z 402 mass chromatograms (Fig. 5), and they were also reported in transition 412→191 in the Niger Delta oil sample (Nytoft et al., 2014). The relatively unstable 3β-methyl-24-nor-18α(H)-oleanane was not detected possibly due to that it is generated during the quite early diagenesis (Petersen et al., 2004). In addition, a doublet of taraxastane (IX) including 19α(H)-taraxastane and a possible 3β-methyl-24-nor-18β(H)-taraxastane before C31 αβ hopane 22R were detected. There is varying abundance of oleanane and taraxastane in the late Oligocene−Miocene shale samples. In the three wells listed in Table 2, the oleanane index (oleanane/C30 αβ hopane) has higher ratios in shale samples in the upper Lingshui-Sanya formations (0.36−1.59; average 0.64), which is mostly higher than in the deeper buried lower Lingshui and middle Lingshui formations. There is lower abundance of taraxastane compared to oleanane, with taraxastane/C30 αβ hopane ranging from 0.02−0.43 (average 0.12). Beside of the regular oleanane and taraxastane, three rearranged oleananes including I (X in Appendix Fig. A1), II (XI in Appendix Fig. A1) and III (XII in Appendix Fig. A1) were tentatively identified mainly based on their mass spectra and relative retention time. All of the rearranged oleananes I, II and III elute between Ts and C29 αβ hopane (Fig. 5) when analyzed by a 30 m HP-5MS column, withthe same molecular weight of 412.3 Da and a base peak at m/z 191.1 (Appendix Fig. A2). The spectrum of compound I is characterised by a fragment triplet at m/z 369.3, 259.2 and 231.2, in which the fragment m/z 369.3 has higher abundance, but is lower than the fragment of m/z 397.3. This tentative identification of compound I is questioned by the lower abundance of the m/z 397.3 fragment compared to the m/z 412.3, which is not completely consistent with the spectrum published by Nytoft et al. (2010). Compound II elutes between I and III, and has very low abundance of fragment including m/z 219.1, 231.2, 259.2 compared to the fragment of m/z 397.2 and 412.3. Compound III partly co-elutes with C29 αβ hopane when analyzed by a 30 m HP-5MS column and it has pronounced fragment of m/z 342.3, m/z 302.3, m/z 231.2 and m/z 205.1 in its mass spectra (Nytoft et al., 2010) (Appendix Fig. A2). The rearranged oleananes I, II and III were integrated in m/z 412 mass chromatogram to eliminate the interference of possible co-elution of lower molecular weight hopanes and oleanane type compounds (<C30). I/C30 αβ hopane has the range of 0.02−0.59 (average 0.24). II/C30 αβ hopane ranges from 0.02−0.73 with an average of 0.25. III/C30 αβ hopane is in the range of 0.02−1.53 (average 0.38).

Bicadinanes and some of their derivatives in aliphatic hydrocarbons were detected and they have varying abundance among samples. Cis-cis-trans-bicadinane (W; XIII), trans-trans-trans-bicadinane (T; XIII) and bicadinanes T1 and R are 5-ring triterpanes that were first found by Grantham et al. (1983) in South Asia oils. The four bicadinanes including W, T, T1, R were reported in worldwide Tertiary and late Cretaceous oil samples (Armanios et al., 1994; Nytoft et al., 2010; Mathur, 2014; Zhu et al., 2018). The bicadinanes W, T, T1 and R have a pronounced fragment of m/z 369.3 and m/z 412.4 in their mass spectra (Appendix Fig. A1). Compound W has a dominant m/z 397.3 and other various fragment. The spectrum of bicadinane T is characterized by higher abundance of m/z 412.3 and m/z 369.3 than fragment m/z 379.4. T1 shares a similar mass spectrum with T but compound T1 has lower abundance of m/z 379.4 than T. Bicadinane R has a dominant fragment triplet at m/z 412.4, 369.4 and 313.3, which is inconsistent with other bicadinane compounds (Appendix Fig. A1). Additionally, some derivatives of bicadinanes in aliphatic hydrocarbon fractions including C31 methyl cis-cis-trans-bicadinane (C31 MeW), C31 methyl trans-trans-trans-bicadinane (C31 MeT) and C31 methyl T1 (C31 MeT1) were detected in m/z 383 mass chromatogram (Fig. 6). C30 bicadinane and two C30 sec-bicadinane are also detected in m/z 151 and 207 mass chromatograms (Fig. 6) but in much lower abundance than W and T. Identifications of these bicadinane compounds were mainly based on the relative retention time and mass spectra published by Armanios et al. (1994) and Zhu et al. (2018). The bicadinane parameter W/C30 αβ hopane has the range of 0.01−1.00 with an average of 0.20, mostly lower than T/C30 αβ hopane (0.05−3.89; average 0.85). T1/C30 αβ hopane ranges from 0.01−0.79 (average 0.18) and R/C30 αβ hopane is in the range of 0.01−0.78 (average 0.17) (Table 2).

Regular steranes (XV) are cycloalkanes derived from the sterols in ancient organisms including eukaryotic photosynthetic algae and higher plants. C27−C29 regular steranes and some diasteranes were detected in the studied shale samples (Fig. 5). Distribution of regular steranes is characterized by higher abundance of C29 ααα 20R sterane relative to its C28 and C27 isomers in most samples, with C29/C27 ααα 20R sterane in the range of 0.88−2.99 (average 1.53). This indicates a terrigenously-dominated organic matter in the shale samples, which is mostly consistent with the interpretation of the dominant terrigenous contribution to the organic matter from the cross-plot of C27/C29 ααα 20R sterane versus Pr/Ph (Fig. 6). Isomerisation ratios of the C29 steranes can be used for assessment of the thermal maturity of crude oils and shales (Seifert and Moldowan, 1978). In Well H29-1, the 20S/(20S+20R) ratio in of C29 regular sterane isomers ranges from 0.35 to 0.51 (average 0.45), which is close to its equilibrium point of 0.60. This ratio in shales of Well B19-2 is in the range of 0.12−0.56 with an average of 0.38. In shale samples of Well S29-2, C29 20S/(20S+20R) sterane ratio is in the range of 0.16−0.45 (0.35).

The TOC was measured in a total of 431 shale samples, including 76 shales in Well L2-1, 67 shales in Well S36-1, 53 shales in Well B19-2, 61 shales in Well B20-1, 44 shales in Well S24-1, 102 shales in Well Y7-4 in the Qiongdongnan Basin, and 28 shales in Well H29-1 in the Yinggehai Basin. Average TOC values of shale samples in the upper Lingshui Formation (0.67%) and the lower Sanya Formation (0.72%) are relatively higher than other formations (0.33%−0.51%) (Table 1). Specifically, TOC in the lower Sanya Formation ranges from 0.18%−2.9%, and it has the range of 0.14−2.40 in the upper Lingshui Formation. The upper Sanya Formation shales have TOC values ranging from 0.08−1.09 (average 0.46). Shales in the upper Yacheng Formation to the middle Lingshui Formation have TOC values in the range of 0.11−2.02 (average TOC ranging from 0.46−0.51). The shallower Meishan Formation shales have relatively lower average TOC values than other formations, with an average values of 0.33% in the lower Meishan Formation and of 0.44% in the upper Meishan Formation. In Well H29-1 of the Yinggehai Basin, shales in the Sanya Formation have TOC values in 0.35−0.45 (average 0.40), mostly higher than that in the lower Meishan Formation (0.22−0.44; average 0.33).

In the depth plots of TOC in the above seven wells, TOC variations with depth in Wells Y7-1, L2-1, S36-1, S24-1, B20-1, B19-2 share the similar higher TOC values in the lower Sanya Formation than in other formations, although TOC values of the lower Sanya Formation shales vary in different wells (Fig. 7). Additionally, there is a trend of progressively higher TOC with decrease in depth from the upper part of the middle Lingshui Formation to the lower Sanya Formation, except in the Well S36-1 due to lack of samples in the middle and upper Lingshui formations (Fig. 7). Similarly, there is generally higher values of TOC in the Sanya Formation than in shallower formations in Well H29-1 of the Yinggehai Basin, although the lower Sanya Formation TOC data were not available due to the lack of samples. The detailed TOC values of all the shale samples in each well were shown in supplementary tables.

Vitrinite reflectance has been widely thought as a reliable tool to measure the thermal maturity of the organic matter in shales. In the Qiongdongnan Basin, shales in the Lingshui-Yacheng formations have Ro>0.6%, indicating that they are buried deeper than the hydrocarbon generation window. In contrast, most of the shallower buried upper Sanya-Meishan formation shales are in immature to low maturity stage, with their Ro<0.6% (Table 1). In addition, the lower Sanya Fomation shales in Wells S36-1, B19-2, B20-1, and Y7-4 are in mature stage, with Ro>0.6% (Supplementary Tables). The thermal maturity parameter of C29 20S/(20S+20R) steranes suggests that shales in the Sanya Formation in Well H29-1 in the Yinggehai Formation mostly have higher thermal maturity than the Lingshui-Sanya formations in Wells B19-2 and S29-2 in the Qiongdongnan Basin.

The relative abundance of pristane (Pr) and phytane (Ph) has been used to assess the depositional environments of organic matter (Didyk et al., 1978), although thermal maturation is also a control on the Pr/Ph ratio (Albrecht et al., 1976; Vuković et al., 2016). Generally, high Pr/Ph ratios (>3) indicate a major terrigenous input in an oxic environment, while low Pr/Ph ratios (<0.8) suggest an anoxic sedimentary environment. Most shales in the upper Lingshui Formation and the lower Sanya Formation have Pr/Ph>3, suggesting an oxic environment. The cross-plot of Ph/nC18 versus Pr/nC17 shows predominantly plant-derived Type III organic matter deposited in an oxidising environment of all the samples (Shanmugam, 1985). This is consistent with the dominant contribution from higher plants to the Oligocene−early Miocene shales in the Ying-Qiong Basin in previous studies (Huang et al., 2003, 2012, 2016a; Ding et al., 2021, 2022a).

The odd-numbered long-chain n-alkanes (>nC25) are diagenetic products of long-chain carboxylic acids that are mostly derived from the leaf wax components of higher plants, whereas shorter chain n-alkanes are typically derived from algae or other aquatic organisms (Cranwell, 1973; Bourbonniere and Meyers, 1996). Terrestrial signatures can be inferred from various n-alkane biomarker parameters, because vascular land plants and emergent macrophytes contain large proportions of nC27, nC29, and nC31 n-alkanes (Eglinton and Hamilton, 1967; Cranwell et al., 1987; Ficken et al., 2000). TAR has been used to distinguish the relative contribution from higher plants and lower aquatic organisms to organic matter (Bourbonniere and Meyers, 1996), although this parameter is likely influenced by thermal maturity. For example, in shales of Well B19-2, there is an increase of TAR from the upper part of the middle Lingshui Formation to the lower Sanya Formation, but it is lower in the shallower buried upper Sanya and lower Meishan formations (Fig. 8). Hence, the dominant control on TAR from thermal maturity over source input can be excluded. The variation of TAR in shales suggests that there was a larger plant input in deposition periods from the upper part of the middle Lingshui Formation to the lower Sanya Formation.

The average chain length of n-alkanes (ACL) has been used to evaluate the averaged n-alkanes distribution of higher plant waxes (Eglinton and Hamilton, 1967). Three aspects including temperature, aridity degree (moisture) in climatic conditions and vegetation species exert controls on ACL in plant waxes (Diefendorf et al., 2011; Bush and McInerney, 2013). In this study, there are markedly higher ACL values of the shale samples in the Sanya Formation (average 28.42) than the deeper buried lower-middle Lingshui formations (average 27.43) and shallower Meishan Formation (average 28.21) in these three wells in Ying-Qiong Basin (Table 2). This is mostly consistent with the increase of TAR from upper part of the middle Lingshui Formation to the lower Sanya Formation in the depth-plot of ACL in Well B19-2 (Fig. 8). Previous studies suggested that leaves of grasses (mostly C4 plants) produce large proportion of nC31 among n-alkanes, with relative high ACL values (Cranwell, 1973; Rommerskirchen et al., 2006). In addition, mangrove plants like Rhizophora mangle have leaf wax n-alkanes with a dominance of nC28-nC31, with ACL ranging from 27.16 and 31.38 (average in 28.23±1.37) (Kumar et al., 2019). However, these two scenarios were ruled out due to the absence of the dominance of grasses or any mangrove pollen in late Oligocene−early Miocene palynological records in the Ying-Qiong Basin (Ding et al., 2021). It is suggested that ACL values of plant waxes are positively related to the temperature and precipitation during plant growth seasons, because vascular plants tend to synthesize longer n-alkanes as their waxy coating in warm and/or dry conditions (Gagosian and Peltzer, 1986; Tipple and Pagani, 2013) compared to those in a colder climate (Schefuß et al., 2003). Therefore, the most likely explanation of higher ACL values in the Sanya Formation than in other formations is that a warmer climate occurred in the early Miocene than in the late Oligocene period.

Paq proxy was used to indicate the relative contribution of aquatic macrophyte relative to emergent and terrestrial plants in the terrigenously-dominated organic matter (Ficken et al., 2000). The generally lower Paq ratio in the Sanya Formation than in the deeper Lingshui Formation in Wells B19-2 and S29-1 (Fig. 8; Table 2) suggest a dominant terrigenous higher plants contribution relative to aquatic macrophyte. Another n-alkane parameter nC31/(nC27+nC29+nC31) has the similar variation with TAR in depth, showing that the dominance of terrigenous plants (C3 woody plants suggested by Ding et al. (2021)) in flora under the warmest Sanya Formation depositional period.

Oleanane and rearranged oleananes are diagenetic products of functionalized components from oleanene, β-amyrin (XVⅠ), and other 3β-functionalized pentacyclic triterpenoids in angiosperms, but does not have a specific source (Grantham et al., 1983; Ten Haven and Rullkötter, 1988; Simoneit et al., 2020). Des-A-oleanane is the product of A-ring degradation of oleanane-type precursors including β-amyrin (Ten Haven et al., 1992; Samuel et al., 2010). Oleanane abundance relative to C30 αβ hopane known as the oleanane index has been widely used to assess the contribution of angiosperms to the organic matter (Philp and Gilbert, 1986; Mathur, 2014; Rudra et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2002). Terpanes X, Y, Z, Z1 were found to be more abundant in shales with relatively high oleanane index (Table 2; Fig. 6). It is proposed that X, Y and Z1 are formed through the biosynthetic pathway of triterpenoids like β-amyrin, because these compounds have the trans configuration that is similar with β-amyrin and 18α-oleanane (Samuel et al., 2010). Rearranged oleananes including compounds I, II, III were thought to be formed by dehydration and rearrangement of higher plant-derived oleanane-typed triterpenoids functionalized at C-3 (Nytoft et al., 2010). In addition, triterpenoids having different skeletons including taraxerol and lupanoids likely contribute to the precursors of oleanane, rearranged oleananes and degraded oleananes (Rullkötter et al., 1994).

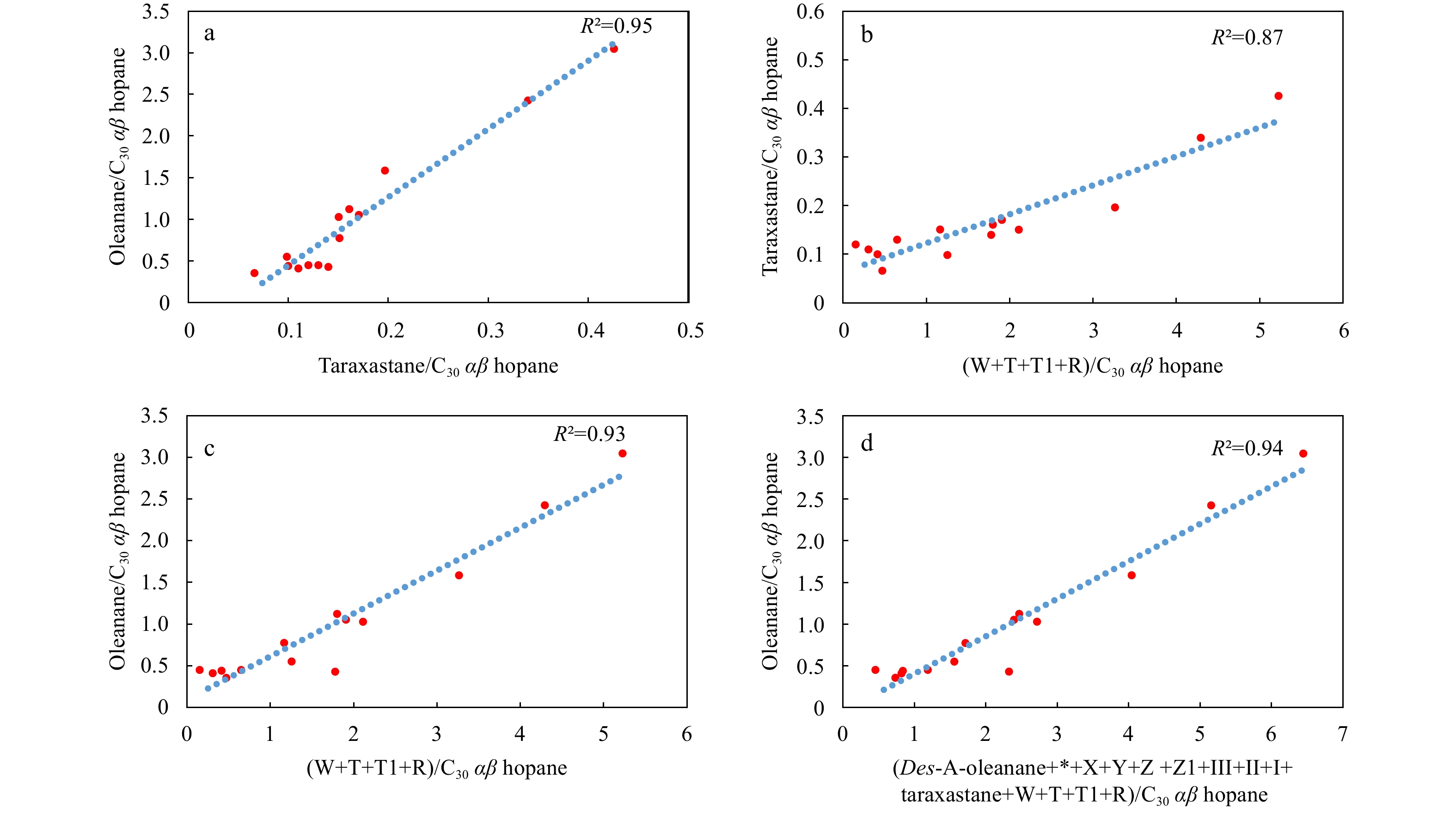

Taraxastane is mainly derived from taraxerol and β-amyrin in angiosperms (Grantham et al., 1983; Ten Haven and Rullkötter, 1988). High abundances of taraxerol relative to β-amyrin were found in the sedimentary organic matter of mangrove forests (Volkman et al., 2007; Koch et al., 2011; Resmi et al., 2016), which are mostly deposited in a terrigenously-dominated marginal marine environment including a deltaic environment under a humid climate (Versteegh et al., 2004; Chu et al., 2020). However, mangrove plants are unlikely the dominant angiosperms in flora, due to that there are much less taraxastane relative to oleanane in the organic matter (Fig. 6; Table 2) and that the relative abundance of taraxastane are positively correlated with oleanane (Fig. 9a; R2=0.95) and bicadinanes (Fig. 9b; R2=0.87) in the Sanya Formation. It This speculation has been partially substantiated by the absence of mangrove pollen in the palynological records in the late Oligocene−early Miocene shales in the Ying-Qiong Basin (Zhang et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2021). However, the possible presence of mangroves cannot be totally excluded due to that the local plant pollen from mangroves are usually transported a much shorter distance relative to pollen from hinterland forests (Urrego et al., 2010), and that oleanane likely originates from precursor compounds in mangrove plants (Resmi et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2019).

Bicadinanes are derived from polycadinene, a resinous polymer produced by tropical/subtropical angiosperms such as the Dipterocarpaceae (Van Aarssen et al., 1992; Murray et al., 1997; Nytoft et al., 2010). Most Dipterocarpaceae is attributed to the tropical/subtropical angiosperms growing in humid conditions, and are mainly distributed in Southeast Asia (Van Aarssen et al., 1992; Paul and Dutta, 2016). Hence, the bicadinane parameter (W+T)/C30 αβ hopane can be used as an indicator of tropical/subtropical plant inputs to the organic matter in source rocks. The increase of the angiosperm-derived oleanane index from the lower part of the middle Lingshui Formation to the lower Sanya Formation (Fig. 10) suggests a large influx of angiosperms in the organic matter. The vertical variation discrepancy between bicadinanes and oleanane relative abundance in Fig. 10 were unexplained.

In the Sanya Formation samples from two wells H29-1 and B19-2 in the Ying-Qiong Basin, there is a positive correlation between the oleanane index and the bicadinane parameter, with R2=0.93 (Fig. 9c). The oleanane index is also positively correlated with sum of other angiosperm-derived compounds (Des-A-oleanane+*+X+Y+Z+Z1+III+II+I+taraxastane+W+T+T1+R) (R2=0.94; Fig. 9d) The pervasive positive correlation between oleanane and bicadinanes and other oleanane-type derivatives was interpreted as that there was a dominant input of topical/subtropical angiosperm plants in the coeval flora, due to that the tropical/subtropical taxa Dipterocarpaceae are the dominant the source of bicadinanes. This explanation was partially corroborated by the dominance of tropical/subtropical taxa including evergreen Quercoidites. Microhenrici in angiosperm pollen in the coeval palynological records in the Ying-Qiong Basin (Ding et al., 2021).

TOC value is fundamental index that measures the organic matter enrichment in sediments (Meyers, 2003). It is also indicative for the amount of well-preserved as opposed to degradation of organic matter in the depositional process (Meyers and Ishiwatari, 1993; Meyers and Lallier-Vergés, 1999). For example, terrigenous organic matter in the Amazon Fan sediments is likely diluted by the planktonic algae and photosynthetic bacteria in the marine environment (Boot et al., 2006). Beside of the algal and/or terrestrial input, the preservation condition likely exerts a control on the organic matter accumulation (Ganai et al., 2018; Kong et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020). It is known that the oxidising environment is not beneficial for the preservation of the organic matter. In the terrigenously-dominated shales in the Ying-Qiong Basin, terrigenous source materials in the organic-richer lower Sanya Formation shales were mainly deposited in the sub-oxidising to oxidising environment compared to organic leaner shales in the less oxidising condition (Fig. 5). This means that the redox condition is not the dominant control on the terrigenous organic matter enrichment in the Ying-Qiong Basin.

In the condition of large influx of terrigenous organic matter in the Ying-Qiong Basin during the period of late Oligocene−early Miocene, the amounts of higher plant inputs largely exceed their degradation amounts during the oxidising depositional environment. For example, in those similar areas where the flux of terrigenous organic matter to the marine environment is high, including the Amazon fan (Hinrichs and Rullkötter, 1997; Boot et al., 2006), the Triassic-Jurassic deltas of the northwest shelf of Australia (Edwards et al., 2004; Cesar and Grice, 2019), the Ying-Qiong Basin in the northwestern South China Sea (Ding et al., 2021) and the Baiyun Sag in the northern South China Sea (Sun et al., 2020), the organic enrichment of marine source rocks was strongly impacted by the input of terrigenous organic matter. In the terrigenously-dominated shales in the Ying-Qiong Basin, the increase of TOC in the terrigenous-dominated shales from the upper part of the middle Lingshui Formation to the lower Sanya Formation suggests a larger supply of higher plant debris during the time intervals. The pronounced higher TOC in the lower Sanya Formation (early Miocene) than other formations (Fig. 2) is mostly consistent with the higher abundance of plant biomarkers that are suggestive of the dominant tropical-subtropical angiosperm origin (Figs 8 and 9) in flora. This can be substantiated by the dominance of broad-leaved tropical/subtropical angiosperms including Quercus and Dicolpopollis kockelii relative to the low abundance of temperate gymnosperm taxa Pinus in plant community (Ding et al., 2021). Hence, the amount of the dominant tropical/subtropical angiosperm inputs was thought as the prime control of terrigenously-dominated organic matter enrichment in study area.

In the South China Sea, high amounts of fluvial runoffs transported sediments and terrigenous organic matter to the sedimentary basin (Huang et al., 2016b; Liu et al., 2016). The formation of these fluvial sediments through chemical weathering in surrounding drainage systems is controlled principally by the East Asian monsoon climate with warm temperature and high precipitation, and subordinately by tectonic activity (Liu et al., 2016). The more intensified East Asian summer monsoon relative to its winter monsoon in the South China Sea at the very early Miocene (about 23.0 Ma, corresponding to the interval of the upper Lingshui-lower Sanya formations) is characterised by a warming and more humid climate, with extra annual precipitation (Wei et al., 2006; Clift et al., 2014). In the northern South China Sea, there was a great amount of sediment input during the late Oligocene−early Miocene, which was related to the more intensified physical erosion caused by stronger East Asian monsoon in association with the uplift of the northern Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 11) (Tada et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019).

In the study area, the larger influx of higher plant materials from the upper part of the middle Lingshui Formation to the lower Sanya Formation was interpreted to due to the warming and more humid climate during the late Oligocene to the early Miocene. This can be corroborated by the increase of the tropical/subtropical angiosperms in flora, as suggested by higher ACL, tropical/subtropical angiosperm-derived oleanane and bicadinanes in the early Miocene shales than in the late Oligocene samples (Figs 8 and 10). This warming change since the late Oligocene (about 24.9 Ma) was also substantiated by the decline of temperate species and the increase of tropical/subtropical angiosperms and ferns in the coeval palynological records (Ding et al., 2021). In Asia, the lower Sanya Formation shales deposited in the warmest early Miocene share the similarity of biomarker characteristics with the Oligocene-Miocene shales and oils in the Borneo (Simoneit et al., 2020), the Upper Assam Basin in India (Mathur, 2014) and the Surma Basin in Bangladesh (Pearson and Alam, 1993) in East Asia and Southeast Asia, with high abundance of high molecular weight n-alkanes, tropical/subtropical angiosperm-derived oleanane, taraxastane and bicadinanes. The above areas have been under the influence of the Southeast Asian and the East Asian summer monsoonal climates since the late Oligocene. The Oligocene-Miocene flora in Southeast Asia and the southernmost part of East Asia are characterized by high abundance of tropical angiosperm plants mainly including the broad-leaved Dipterocarpaceae, Palmae, Araucariaceae, Pandanceae and various hydrophilous ferns (Bande and Prakash, 1986; Sun and Wang, 2005; Jacques et al., 2011; Herman et al., 2017). The interpreted starting of the warming climate from about 24.9 Ma in the Ying-Qiong Basin is almost consistent with the initiation of the intensified East Asian summer monsoon since the late Oligocene in the South China Sea (Clift et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2021). In this intensified monsoonal climate, the larger annual precipitation is beneficial for the plant growth and the fluvial transportation process of plant materials through the delta system into the marginal marine environment (An et al., 2001; Reuter et al., 2013).

In the Ying-Qiong Basin, the maximum influx period of terrigenous organic matter during deposition of the lower Sanya Formation (about 23.0−ca.18.3 Ma) is largely consistent with the peak East Asian monsoon intensity at 21–23 Ma in the South China Sea (Clift et al., 2014). That is because that the river borne terrigenous flux can be intensified by stronger annual precipitation and warming climate in the coastally monsoonal zones (Fig. 11) (Khare, 2018; Ding et al., 2021). After the early Miocene, the reduced annual precipitation in the weakened East Asian summer monsooal climate in the South China Sea resulted in less influx of terrigenous matter including the river-borne higher plant debris.

It has been suggested that the colder and drier climatic condition in combination with a lowered sea level would allow rivers to dump their sediment loads closer to the shelf edge, promoting enhanced fluvial inputs into the basin (Hoogakker et al., 2004). The abundant terrigenous n-alkanes input in the South China Sea was thought to be sensitive to changes in river inputs induced by sea-level fluctuations (Pelejero et al., 1999; Kienast et al., 2003; Huang and Tian, 2012). In the Ying-Qiong Basin, there are higher abundance of terrigenous n-alkanes (>nC27) in the early Miocene sedimentary rocks (corresponding to deposition of the lower Sanya Formation) compared to other formations. However, it is less likely that the influence of sea level change outweighs the large influx of the river-borne plant debris on terrigenous organic matter accumulation, due to that there was a relatively stable sea level fluctuation in the early Miocene in the South China Sea (Zhang et al., 2019). Nevertheless, a deeper investigation is needed to study the influence of the high-resolution sea level fluctuation on the organic matter enrichments in shales over geological time.

One way to understand the proposed tectonic-organic matter enrichment interactions is to define the history and timing of major tectonic and climate changes and abundance variation of organic matter in shales in the South China Sea. During the period of 23−15 Ma, the lithostratigraphic records analysed from the ODP Site 1148 suggested a stable spreading to end of spreading in the paleoceanographic evolution of the South China Sea (Li et al., 2006). Decrease in of subsidence rate during the drifting stage (32–17 Ma) also provide evidence of tectonically stable and shallow water environment of the South China Sea (Ding et al., 2014). Hence, it was thought that the spreading of the South China Sea during the late Oligocene−early Miocene has limited influence on the coeval terrigenous organic matter accumulation in the northern South China Sea. Another regional tectonic factor in association with the terrigenous influx and monsoonal climate in the South China Sea is the periodical uplifts of the northern Tibet Plateau during about 25–20 Ma (Clift et al., 2014, 2015; Tada et al., 2016). It is widely acknowledged that the uplift of the northern Tibet Plateau should have further intensified the East Asian summer monsoon and the East Asian winter monsoon during the late Oligocene−early Miocene (Guo et al., 2002; Clift et al., 2008; Molnar et al., 2010; Tada et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2021). The regional tectonic events of uplift of the northern Tibet Plateau in association with the stronger East Asian monsoonal climate likely played an indirect role in the large influx of the terrigenous organic matter in the early Miocene shales.

(1) Vertical variations of a total of 430 TOC and Rock-Eval data and the associated higher plant-derived biomarkers in the late Oligocene−early Miocene marine shale samples were first reported in the Ying-Qiong Basin, South China Sea. This suggests that there is an increase of terrigenous organic matter content in shales from the upper part of the middle Lingshui Formation (late Oligocene) to the lower Sanya Formation (early Miocene) in the Ying-Qiong Basin.

(2) There are more abundant angiosperm-derived biomarkers and their derivatives including higher molecular weight n-alkanes, oleanane and its three-four ring derivatives, rearranged oleananes, four isomers of bicadinanes in shales of the lower Sanya Formation than in the late Oligocene shales. Most of these biomarker characteristics have not been reported elsewhere in the South China Sea. The lower Sanya Formation shales have plant-derived biomarker characteristics that are indicative for tropical/subtropical plants under the warm and humid climate.

(3) The influx of higher plants mainly from tropical/subtropical angiosperms was thought as the prime control of terrigenous organic matter enrichment in the marine source rocks of the Ying-Qiong Basin. Organic redox condition, sea level changes and sea floor spreading of the South China Sea were thought to have a lesser influence on the terrigenous organic matter enrichment compared to the influx of plant materials. The extra annual precipitation brought by the gradually intensified East Asian summer monsoon during the late Oligocene−early Miocene was beneficial for the large influx of the river-borne terrigenous organic matter.

Acknowledgements: The authors appreciate gratefully to the Zhanjiang Branch of the China National Offshore Oil Corporation for samples and data collection. Wenjing Ding thank the China University of Geosciences (Beijing) and Macquarie University for the cotutelle PhD project. Simon C. George and Lian Jiang from Macquarie University are acknowledged for their previous instructions on research work methods, lab work and paper writing. Shanshan Zhou and Wei Li from CNOOC Research Institute Limited, Beijing are thanked for their advice on improving the quality of the manuscript and the figures. Guo Chen from Yangtze University is also thanked for the helpful discussion.|

Ahmed M, George S C. 2004. Changes in the molecular composition of crude oils during their preparation for GC and GC-MS analyses. Organic Geochemistry 35(2): 137–155

|

|

Akinlua A, Torto N. 2011. Geochemical evaluation of Niger Delta sedimentary organic rocks: a new insight. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 100(6): 1401–1411. doi: 10.1007/s00531-010-0544-z

|

|

Albrecht P, Vandenbroucke M, Mandengué M. 1976. Geochemical studies on the organic matter from the Douala Basin (Cameroon)—I. Evolution of the extractable organic matter and the formation of petroleum. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 40(7): 791–799. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(76)90031-4

|

|

An Zhisheng, Kutzbach J E, Prell W L, et al. 2001. Evolution of Asian monsoons and phased uplift of the Himalaya-Tibetan plateau since Late Miocene times. Nature, 411(6833): 62–66. doi: 10.1038/35075035

|

|

Armanios C, Alexander R, Kagi R I, et al. 1994. Fractionation of sedimentary higher-plant derived pentacyclic triterpanes using molecular sieves. Organic Geochemistry, 21(5): 531–543. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(94)90104-X

|

|

Baas M, Pancost R, Van Geel B, et al. 2000. A comparative study of lipids in Sphagnum species. Organic Geochemistry, 31(6): 535–541. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00037-1

|

|

Bande M B, Prakash U. 1986. The tertiary flora of Southeast Asia with remarks on its palaeoenvironment and phytogeography of the Indo-Malayan region. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 49(3–4): 203–233

|

|

Boot C S, Ettwein V J, Maslin M A, et al. 2006. A 35, 000 year record of terrigenous and marine lipids in Amazon Fan sediments. Organic Geochemistry, 37(2): 208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2005.09.002

|

|

Bourbonniere R A, Meyers P A. 1996. Sedimentary geolipid records of historical changes in the watersheds and productivities of Lakes Ontario and Erie. Limnology and Oceanography, 41(2): 352–359. doi: 10.4319/lo.1996.41.2.0352

|

|

Bush R T, McInerney F A. 2013. Leaf wax n-alkane distributions in and across modern plants: Implications for paleoecology and chemotaxonomy. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 117: 161–179. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2013.04.016

|

|

Cesar J, Grice K. 2019. Molecular fingerprint from plant biomarkers in Triassic-Jurassic petroleum source rocks from the Dampier Sub-Basin, Northwest Shelf of Australia. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 110: 189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.07.024

|

|

Chu Mengfan, Sachs J P, Zhang Hailong, et al. 2020. Spatiotemporal variations of organic matter sources in two mangrove-fringed estuaries in Hainan, China. Organic Geochemistry, 147: 104066. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2020.104066

|

|

Clift P D, Brune S, Quinteros J. 2015. Climate changes control offshore crustal structure at South China Sea continental margin. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 420: 66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpgl.2015.03.032

|

|

Clift P D, Hodges K V, Heslop D, et al. 2008. Correlation of Himalayan exhumation rates and Asian monsoon intensity. Nature Geoscience, 1(12): 875–880. doi: 10.1038/ngeo351

|

|

Clift P, Lee J I, Clark M K, et al. 2002. Erosional response of South China to arc rifting and monsoonal strengthening; a record from the South China Sea. Marine Geology, 184(3/4): 207–226

|

|

Clift P D, Wan Shiming, Blusztajn J. 2014. Reconstructing chemical weathering, physical erosion and monsoon intensity since 25 Ma in the northern South China Sea: A review of competing proxies. Earth-Science Reviews, 130: 86–102. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.01.002

|

|

Cranwell P A. 1973. Chain-length distribution of n-alkanes from lake sediments in relation to post-glacial environmental change. Freshwater Biology, 3(3): 259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1973.tb00921.x

|

|

Cranwell P A, Eglinton G, Robinson N. 1987. Lipids of aquatic organisms as potential contributors to lacustrine sediments-II. Organic Geochemistry, 11(6): 513–527. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(87)90007-6

|

|

Dahl K A, Oppo D W, Eglinton T I, et al. 2005. Terrigenous plant wax inputs to the Arabian Sea: Implications for the reconstruction of winds associated with the Indian Monsoon. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 69(10): 2547–2558. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2005.01.001

|

|

Didyk B M, Simoneit B R T, Brassell S C, et al. 1978. Organic geochemical indicators of palaeoenvironmental conditions of sedimentation. Nature, 272(5650): 216–222. doi: 10.1038/272216a0

|

|

Diefendorf A F, Freeman K H, Wing S L, et al. 2011. Production of n-alkyl lipids in living plants and implications for the geologic past. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 75(23): 7472–7485. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.09.028

|

|

Ding Wenjing, Hou Dujie, Gan Jun, et al. 2021. Palaeovegetation variation in response to the late Oligocene-early Miocene East Asian summer monsoon in the Ying-Qiong Basin, South China Sea. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 567: 110205

|

|

Ding Wenjing, Hou Dujie, Gan Jun, et al. 2022a. Sedimentary geochemical records of late Miocene-early Pliocene palaeovegetation and palaeoclimate evolution in the Ying-Qiong Basin, South China Sea. Marine Geology, 445: 106750. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2022.106750

|

|

Ding Wenjing, Hou Dujie, Gan Jun, et al. 2022b. Aromatic hydrocarbon signatures of the late Miocene-early Pliocene in the Yinggehai Basin, South China Sea: Implications for climate variations. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 142: 105733. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.105733

|

|

Ding Wenjing, Hou Dujie, Zhang Weiwei, et al. 2018. A new genetic type of natural gases and origin analysis in Northern Songnan-Baodao Sag, Qiongdongnan Basin, South China Sea. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 50: 384–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2017.12.003

|

|

Ding Weiwei, Li Jiabiao, Dong Congzhi, et al. 2014. Oligocene–Miocene carbonates in the Reed Bank area, South China Sea, and their tectono-sedimentary evolution. Marine Geophysical Research, 36(2): 149–165

|

|

Edwards D, Preston J, Kennard J, et al. 2004. Geochemical characteristics of hydrocarbons from the Vulcan Sub-basin, western Bonaparte Basin, Australia. In: Ellis G K, Baillie P W, Munson T J, eds. Proceedings of the Timor Sea Symposium, Special Publication. Darwin, Australian: Northern Territory Geological Survey, 169–201

|

|

Eglinton G, Hamilton R J. 1967. Leaf epicuticular waxes: The waxy outer surfaces of most plants display a wide diversity of fine structure and chemical constituents. Science, 156(3780): 1322–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3780.1322

|

|

Fan Caiwei, Xu Changgui, Xu Jie. 2021. Genesis and characteristics of Miocene deep-water clastic rocks in Yinggehai and Qiongdongnan Basins, northern South China Sea. Acta Geologica Sinica-English Edition, 95(S1): 153–166

|

|

Feng Yangwei, Ren Yan, Lyu Chengfu, et al. 2021. Seismic recognition and origin of Miocene Meishan Formation contourite deposits in the southern Qiongdongnan Basin, northern South China Sea. Acta Geologica Sinica-English Edition, 95(1): 131–141. doi: 10.1111/1755-6724.14626

|

|

Ficken K J, Li B, Swain D L, et al. 2000. An n-alkane proxy for the sedimentary input of submerged/floating freshwater aquatic macrophytes. Organic Geochemistry, 31(7–8): 745–749

|

|

Gagosian R B, Peltzer E T. 1986. The importance of atmospheric input of terrestrial organic material to deep sea sediments. Organic Geochemistry, 10(4–6): 661–669

|

|

Ganai J A, Rashid S A, Romshoo S A. 2018. Evaluation of terrigenous input, diagenetic alteration and depositional conditions of Lower Carboniferous carbonates of Tethys Himalaya, India. Solid Earth Sciences, 3(2): 33–49. doi: 10.1016/j.sesci.2018.03.002

|

|

Golonka J, Krobicki M, Pająk J, et al. 2006. Global Plate Tectonics and Paleogeography of Southeast Asia. Kraków, Poland: Faculty of Geology, Geophysics and Environmental Protection, AGH University of Science and Technology, 122, http://www-odp.tamu.edu/publications/155_SR/CHAP_34.PDF [1998-05-01]/[2022-01-01]

|

|

Goñi M A, Ruttenberg K C, Eglinton T I. 1997. Sources and contribution of terrigenous organic carbon to surface sediments in the Gulf of Mexico. Nature, 389(6648): 275–278

|

|

Grantham P J, Pesthwma J, Baak A. 1983. Triterpanes in a number of Far-Eastern crude oils. In: Bjoroy M, Albrecht C, eds. Advances in Organic Geochemistry 1981. New York: Wiley, 675–683

|

|

Guo Zhengtang, Ruddiman W F, Hao Qingzhen, et al. 2002. Onset of Asian desertification by 22 Myr ago inferred from loess deposits in China. Nature, 416(6877): 159–163

|

|

Hautevelle Y, Michels R, Malartre F, et al. 2006. Vascular plant biomarkers as proxies for palaeoflora and palaeoclimatic changes at the Dogger/Malm transition of the Paris Basin (France). Organic Geochemistry, 37(5): 610–625

|

|