| Citation: | Shengyi Mao, Guodong Jia, Xiaowei Zhu, Nengyou Wu, Daidai Wu, Hongxiang Guan, Lihua Liu. Last glacial terrestrial vegetation record of leaf wax n-alkanols in the northern South China Sea: Contrast to scenarios from long-chain n-alkanes[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2022, 41(8): 22-30. doi: 10.1007/s13131-021-1917-9 |

Long-chain (>C24) n-alkyl compound classes, i.e., C27–31 odd carbon-numbered n-alkanes and C28–32 even carbon-numbered n-alkanols and n-fatty acids (FAs), are major components of epicuticular waxes of vascular higher plant leaves (Eglinton and Hamilton, 1967). Different photosynthetic plant types generally possess diverse chain length distributions and contain variable carbon isotopes (δ13C) in long-chain n-alkyl lipids (e.g., Diefendorf and Freimuth, 2017, and references therein). Therefore, chain length-dependent proxies such as carbon preference index (CPI) and average chain length (ACL), together with δ13C compositions have been widely applied to the terrestrial, atmospheric and aquatic environments for terrestrial vegetation reconstruction (e.g., Diefendorf and Freimuth, 2017, and references therein). However, few studies were reported for the application of long-chain n-alkanols and/or n-FAs. This is surprising since these three n-alkyl lipid classes are produced from a common precursor (Cheesbrough and Kolattukudy, 1984; Post-Beittenmiller, 1996). It could be, at least in part, attributed to that long-chain n-alkanols and n-FAs containing functional groups (i.e., hydroxyl and carboxyl, respectively) are more vulnerable to diagenetic degradation (Cranwell, 1981; Meyers and Eadie, 1993; Meyers and Ishiwatari, 1993; Hoefs et al., 2002; Damsté et al., 2002; van Dongen et al., 2008), thereby obscuring their fidelity to original vegetation signals in certain environments. Previous sediment measurements (Hoefs et al., 2002; Damsté et al., 2002) have demonstrated variable degradation rates and rate constants among long-chain n-alkyl compound classes with n-alkanes more resistance to aerobic degradation than n-FAs and n-alkanols, implying certain alternation on sedimentary n-FA and n-alkanol records under oxic conditions. This occurrence may in turn complicate the applicability of long-chain n-alkanes to trace original vegetation signals, as decarboxylation and dehydration of functionalized n-FAs and n-alkanols has been found to occur rapidly in sediments (Cranwell, 1981; Sun and Wakeham, 1994; Sun et al., 1997; Hoefs et al., 2002), thus likely resulting in diagenesis-induced enhancement of their respective n-alkanes counterparts (i.e., carbon number minus one). Nonetheless, the aerobic degradation may also lead to significant and even complete remineralization loss of labile n-FAs and n-alkanols (e.g., Wakeham et al., 2007, and references therein), implying the reliability of long-chain n-alkanes to reflect original terrestrial signals due to minimal diagenetic contribution of corresponding n-FAs and n-alkanols.

As one of the largest marginal seas in the western Pacific, the South China Sea (SCS) has received extensive attention on long-chain n-alkanes, especially chain length proxies for terrestrial vegetation reconstruction and related climate change (Hu et al., 2003; Pelejero, 2003; He et al., 2008, 2017; Shintani et al., 2011; Huang and Tian, 2012; Zhou et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013, 2015; Xu et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018b; Liu et al., 2019). Although some studies have demonstrated the application of long-chain n-alkanols and/or n-FAs (Hu et al., 2009; Shintani et al., 2011; Strong et al., 2012, 2013; Zhu et al., 2014, 2016; He et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2019), these studies mostly focus on the Zhujiang River Estuary (ZRE). To our best knowledge, two case studies have presented detailed data of chain length distributions and δ13C compositions of long-chain n-FAs, one from the ZRE (Strong et al., 2013) and another from the open northern SCS (Zhu et al., 2014). The molecular distributions of long-chain n-alkanols were also reported in suspended particulate material (SPM) and/or surface sediments from the ZRE (Hu et al., 2009; Strong et al., 2012, 2013; Guo et al., 2019), while δ13C records of long-chain n-alkanols were only presented in sediment cores from the open northern SCS (Zhu et al., 2016; He et al., 2017). Consequently, it is still ambiguous in terms of the application of molecular distributions and δ13C compositions of long-chain n-alkanols into the terrestrial vegetation reconstruction in the SCS. In this study, sedimentary records of long-chain n-alkanols in a core from the northern SCS were investigated to revisit this issue. Long-chain n-alkanes were also analyzed for a parallel comparison with long-chain n-alcohol records to avoid problems and limitations using a single n-alkyl compound class.

The vegetation on the mainland adjacent to the northern SCS is mainly composed of subtropical coniferous forest, subtropical/tropical evergreen broadleaf forest and deciduous shrub, and their distributions are largely controlled by latitude and altitude variations (China Vegetation Editorial Committee, 1980). Natural subtropical evergreen broadleaf forest is mostly common in low hills (i.e., 600–1 500 m elevation) in southern China, i.e., Jiangxi and Fujian. In contrast, tropical evergreen broadleaf forest is generally predominant in the lowlands (i.e., <600 m elevation) of Hainan and Taiwan Islands (China Vegetation Editorial Committee, 1980). Temperate deciduous broadleaf forest and cold-temperate coniferous forest (i.e., Abies and Picea) are substantially dominant in higher mountains, i.e., the Yushan Mountains in central Taiwan Island, the highest range (3 925 m elevation) in the region (China Vegetation Editorial Committee, 1980). The local evergreen broadleaf forest, especially along the coastal plain, has been mostly destroyed by anthropogenic activities since the 1960s and is rapidly colonized by cultivated vegetation, i.e., subtropical coniferous forest (i.e., Pinus massoniana) and tropical/subtropical grassland (China Vegetation Editorial Committee, 1980).

The different vegetation communities on the mainland directly result in remarkable spatial variations of modern pollen distributions in proximate marine surface sediments. For example, Pinus is the major pollen taxa with extremely high contents in the coastal area as a consequence of extensively planting along the coastal region (Dai et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2017). In contrast, high-altitude conifers, such as Picea and Abies, are almost exclusively present in southwest of Taiwan Island (Dai et al., 2014) as higher mountains in the region can favor their massive development. Moreover, relatively higher pollen contents are found around the ZRE than in other inshore areas (Dai et al., 2014). The result suggests that the key influence on modern pollen distribution in the northern SCS is related to the Zhujiang River, with this catchment providing the main fluvial transport of pollen to the northern SCS (Dai et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2017). Therefore, it shows a generally decreased trend in pollen contents along the gradient from coastal to open regions (Dai et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2017).

In this study, one sediment core (Site 4B) from the continental slope of the northern SCS (20.14°N, 116.52°E; Fig. 1) was studied. The core Site 4B was located adjacent to several other cores (Fig. 1), which have been well studied for fossil pollen (Sun and Li, 1999; Sun et al., 2000, 2003; Chang et al., 2013; Dai et al., 2015, 2018; Dai and Weng, 2015; Yu et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019) and/or terrestrial n-alkyl lipid biomarkers (He et al., 2008, 2017; Shintani et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019). These published data can provide a general frame of dynamics on paleovegetation and paleoclimate in this region, and thus can be utilized for a general comparison with our sedimentary records of long-chain n-alkanols and n-alkanes as a clue to evaluate their implications in the northern SCS. The Site 4B of the core has been reported for molecular distributions and/or δ13C compositions of alkane and alcohol fractions in our previous studies (Zhu et al., 2016, 2018, 2019), in which detailed information of core collection, separation, preservation and age dating, and experiments of lipid extraction and separation for different fractions, as well as instrumental analysis, identification and quantitation of alkane and alcohol compounds can be found.

Briefly, the freeze-dried and powdered samples were extracted with dichloromethane (DCM)/MeOH (9:1, v/v) for 72 h in a Soxhlet apparatus, followed by saponification with KOH/MeOH (1 mol/L) and extraction with hexane. The neutral lipids were purified using silica gel chromatography to isolate alkane, aromatic and alcohol fractions by elution with n-hexane, benzene and MeOH, respectively. The alcohol fraction was converted to trimethylsilyl derivatives with bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) prior to gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and gas chromatography-isotope ratio-mass spectrometry (GC-IR-MS) analyses at the State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The alkane fraction was performed only for GC-MS analysis, thereby leading to a lack of a parallel comparison between δ13C records of long-chain n-alkanols and n-alkanes. Nevertheless, the applicability of long-chain n-alkane records, i.e., CPI and ACL in the study core could be roughly assesed by comparing with published data in nearby cores (He et al., 2008; Shintani et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019). Therefore, the long-chain n-alkanes without δ13C records were still useful for an effective comparison with long-chain n-alkanols to evaluate their relationships and implications. Seven sedimentary intervals were chosen for accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C measurements based on Globigerinoides ruber and/or Globigerinoides sacculifer at the State Key Laboratory of Isotope Geochemistry, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences. After correction and conversion into calendar ages, the topmost measured sample has an age of 1.954 ka, and the bottommost sample has an age of 41.596 ka (Zhu et al., 2019). The age-depth relationship based on the seven age control point is near linear, and the age of each sample was determined through linear interpolation between age control points (Zhu et al., 2019).

The CPI and ACL proxies contents of long-chain n-alkanes were calculated by following equations (Bray and Evans, 1961):

| $$\begin{split} {\rm{CPI}}_{25-33}= &0.5\times[\Sigma {\rm{Odd}}({\rm{C}}_{25}-{\rm{C}}_{33})/\Sigma {\rm{Even}}({\rm{C}}_{24}-{\rm{C}}_{32})+\\ &\Sigma {\rm{Odd}}({\rm{C}}_{25}- {\rm{C}}_{33})/\Sigma {\rm{Even}}({\rm{C}}_{26}-{\rm{C}}_{33})],\end{split}$$ | (1) |

| $$\begin{split} {\rm{ACL}_{25-33}}= &({\rm{C}_{25}}\times 25+{\rm{C}_{27}}\times 27+{\rm{C}_{29}}\times 29+{\rm{C}}_{31}\times 31+\\ &{\rm{C}_{33}}\times 33)/ [\Sigma {\rm{Odd}}({\rm{C}_{25}}-{\rm{C}_{33}})].\end{split}$$ | (2) |

The even carbon-numbered long-chain n-alkanols are generally biosynthesized correspondingly to (–1) odd carbon-numbered n-alkanes from the common precursor (Cheesbrough and Kolattukudy, 1984; Post-Beittenmiller, 1996). Accordingly, CPI and ACL proxies contents of long-chain n-alkanols were calculated by following equations:

| $$\begin{split} {\rm{CPI}}_{26-34}= &0.5\times[\Sigma {\rm{Even}}({\rm{C}}_{26}-{\rm{C}}_{34})/\Sigma {\rm{Odd}}({\rm{C}}_{25}-{\rm{C}}_{33})+\\ &\Sigma {\rm{Odd}}({\rm{C}}_{26}- {\rm{C}}_{34})/\Sigma {\rm{Odd}}({\rm{C}}_{27}-{\rm{C}}_{35})],\end{split}$$ | (3) |

| $$\begin{split} {\rm{ACL}_{26-34}}= &({\rm{C}_{26}}\times 26+{\rm{C}_{28}}\times 28+{\rm{C}_{30}}\times 30+{\rm{C}}_{32}\times 32+\\ &{\rm{C}_{34}}\times 34)/ [\Sigma {\rm{Even}}({\rm{C}_{26}}-{\rm{C}_{34}})].\end{split}$$ | (4) |

Previous study showed that the C26, C28 and C30 n-alkanols had a reasonably coherent stratigraphic trend of δ13C variations (Zhu et al., 2016), indicating their common source of higher plants. Hence, we here use the weighted mean average δ13C of C26, C28 and C30 n-alkanols to provide a general view of the δ13C variations of each individual n-alcohol, as the case for long-chain n-alkanes in nearby cores (Zhou et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2019). The weighted mean δ13C of C26–30 n-alkanols was calculated by following equation:

| $$\begin{split} {\delta^{13}}{\rm{C}_{26-30}}=&(\delta^{13}{\rm{C}_{26}}\times{\rm{C}_{26}}+\delta^{13}{\rm{C}}_{28}\times{\rm{C}_{28}}+\\ &\delta^{13}{\rm{C}}_{30}\times{\rm{C}_{30}})/[{\Sigma}{\rm{Even}}({\rm{C}}_{26}-{\rm{C}}_{30})]. \end{split}$$ | (5) |

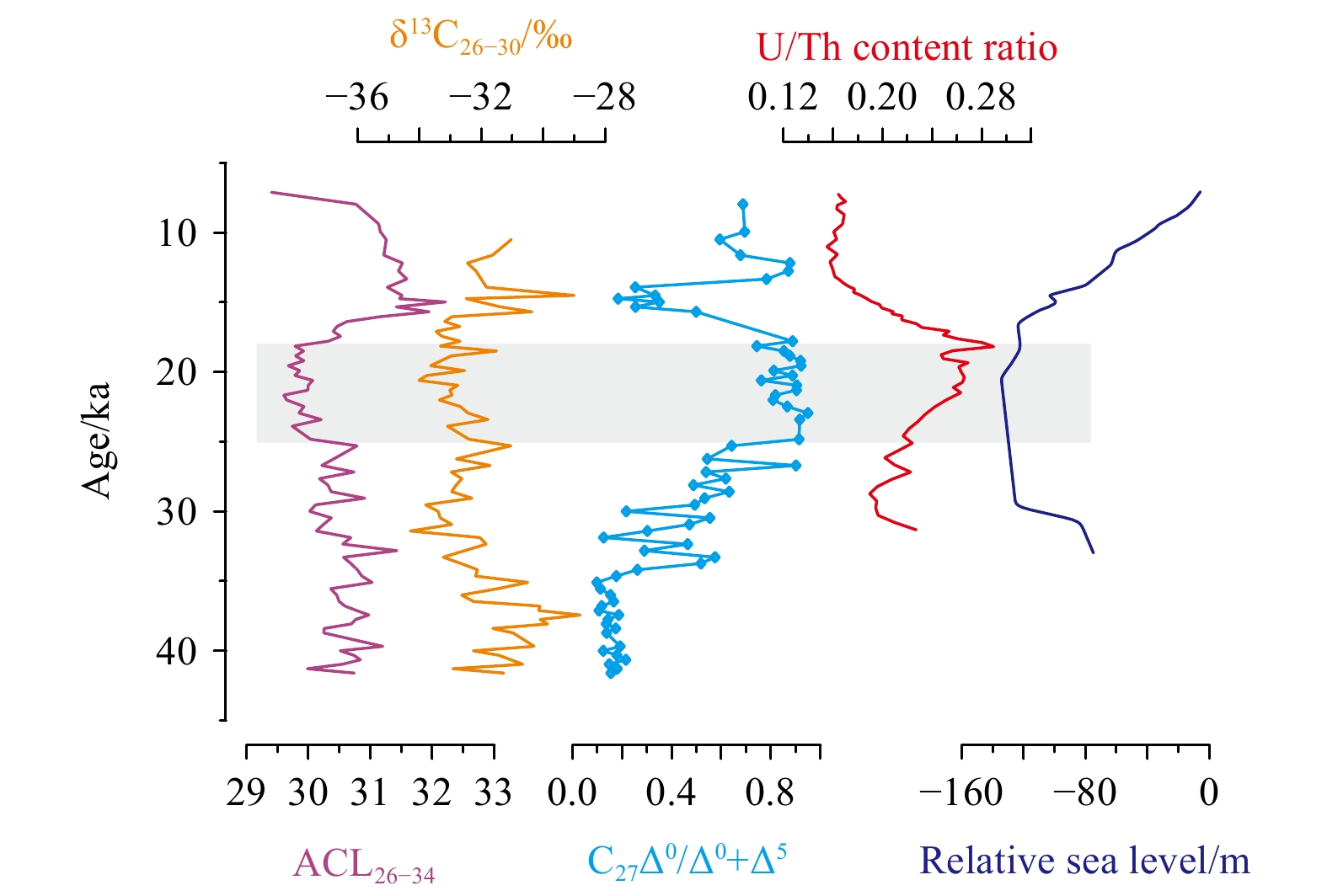

The upper six samples (0–30 cm intervals) were not suitable for lipid measurements due to contamination during sample treatment in the laboratory. Therefore, long-chain n-alkanols and n-alkanes in sediments at 30–300 cm intervals were analyzed, covering a time period of ~42–7 ka. Overall, long-chain n-alkanes showed an odd-over-even predominance with CPI25–33 values from 1.5 to 3.8 (average 2.7), whereas long-chain n-alkanols exhibited an even-over-odd predominance with CPI26–34 values from 8.2 to 18.9 (average 12.9) (Fig. 2). The distributions of long-chain n-alkanes and n-alkanols strongly suggested a predominant input of terrestrial higher plants. However, changes on degradation or preservation of long-chain n-alkanols and n-alkanes might be reflected by the two CPI records, which changed almost in parallel down core sediments (Fig. 2). Moreover, the ACL26–34 values (29.4–32.2 in range and 30.6 on average) changed synchronously with δ13C26–30 records, which ranged from –34.3‰ to –28.8‰ (average –32.2‰) (Fig. 2). The substantially low values of ACL26–34 and δ13C26–30 strongly indicated a dominance of C3 plant input during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (Conte et al., 2003; Chikaraishi et al., 2004; Rommerskirchen et al., 2006; Chikaraishi and Naraoka, 2007; Vogts et al., 2009; Diefendorf et al., 2011, 2015; Mortazavi et al., 2012; Diefendorf and Freimuth, 2017). However, the long-chain n-alcohol records displayed inconsistent trends with ACL25–33 variations (28.1–29.7 in range and 29.2 on average), which likely suggested a more contribution of C4 plants during the LGM (Fig. 2).

The occurrence of different terrestrial vegetation evolution derived from long-chain n-alkanes and n-alkanols suggested that factors controlling their distributions during bio- and diagenetic processes were more complicated than expected. In the present study, the ACL25–33 records of long-chain n-alkanes matched well with published data in adjacent cores (He et al., 2008; Shintani et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019), hence largely ruling out the possibility of systematic analytic differences and estimation accuracies on long-chain n-alkanes from different studies. The analytic difference between the two n-alkyl lipid classes was also less possible because the two CPI records shared a similar trend down the core (Fig. 2). Moreover, the conspicuous discrepancy between the two n-alkyl lipid classes was observed in the same core, thus negating the issue of site-to-site correlation. Although mechanisms for this discrepancy remained unclear, the reasonable interpretations could be (1) diagenetic degradation on functionalized long-chain n-alkanols (Cranwell, 1981; Meyers and Eadie, 1993; Meyers and Ishiwatari, 1993; Hoefs et al., 2002; Damsté et al., 2002; van Dongen et al., 2008) that likely obscured their response to vegetation variation; (2) diverse responses of functionalized and non-functional n-alkyl lipid classes to vegetation signals in different source area (Galy et al., 2011; Ponton et al., 2014; Hemingway et al., 2016); and (3) large variations among different species of C3/C4 plants that produce variable compositions of n-alkyl lipid classes (Diefendorf and Freimuth, 2017), leading to a bias in sedimentary records of long-chain n-alkanols and n-alkanes towards different vegetation signals.

Due to lacks of functional groups, long-chain n-alkanes are more resistant to degradation than functionalized n-FAs and n-alkanols (Cranwell, 1981; Meyers and Eadie, 1993; Meyers and Ishiwatari, 1993; Hoefs et al., 2002; Damsté et al., 2002; van Dongen et al., 2008). However, to date, almost no detailed studies of diagenetic degradation on long-chain n-alkanols were reported, and thus the influence of degradation on their chain length and δ13C variations remained ambiguous. However, a total increase in ACL26–32 values from surface SPM samples to underlying surface sediments was observed at sampling sites in the ZRE (Fig. 3), likely suggesting the preferential loss of shorter chain homologues due to degradation of terrestrial-derived long-chain n-alkanols. The distribution of ACL26−32 values (average 28.3; Fig. 3) in surface SPM samples was roughly consistent with modern vegetation ecosystem in the Zhujiang River Basin, showing a dominance of C3 plants, as this flora generally shows a peak in C28 or C30 n-alcohol (Vogts et al., 2009). Although CPI26−34 is also a good indicator to assess chain length variations of n-alkanols between SPM samples and surface sediments, it is impossible here to perform this comparison due to insufficient CPI26−34 records in SPM samples, which were mainly induced by extremely low contents of long-chain odd carbon-numbered n-alkanols in most SPM samples (Guo, 2015). The diagenetic alteration and preservation of bulk organic matter and lipid biomarkers are largely determined by oxygen exposure time (Müller and Suess, 1979; Hartnett et al., 1998), which integrates the bottom water oxygen content and the residence time at the sediment-water interface. Therefore, the parallel comparison of ACL26–32 values in SPM samples with those in surface sediments (Fig. 3) likely suggested the occurrence of aerobic degradation of long-chain n-alkanols at the sediment-water interface at sampling sites, where bottom waters are oxygen rich (Guo, 2015; Guo et al., 2015). The results also demonstrated that the seasonal or temperature variations were less significant in modulating ACL26–32 distributions, as evidenced by very similar values in seasonal SPM samples (Fig. 3).

The contemporary study in the ZRE showing that aerobic degradation on long-chain n-alkanols could result in an increase in ACL26–32 values (Fig. 3) matched reasonably with our core-study showing a substantially negative correlation between ACL26–34 and CPI26–34 indicative of diagenetic alternation (Fig. 4). However, a positive correlation was observed between ACL25–33 and CPI25–33 (Fig. 4), which was also documented in previous studies in nearby cores (He et al., 2008, 2017; Shintani et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2017), likely suggesting that ACL25–33 variations were not mainly influenced by the diagenetic degradation. The contrast scenario between ACL26–34 and ACL25–33 observed here is consistent with general findings showing that long-chain n-alkanes are more resistance to aerobic degradation than functionalized n-alkanols (Cranwell, 1981; Meyers and Eadie, 1993; Meyers and Ishiwatari, 1993; Hoefs et al., 2002; Damsté et al., 2002; van Dongen et al., 2008). Moreover, the positive relationship between ACL25–33 and CPI25–33 (Fig. 4) could further indicate the absence of aerobic conversion of long-chain n-alkanols to corresponding n-alkanes likely due to significant loss of n-alkanols during aerobic remineralization (e.g., Wakeham et al., 2007 and references therein). Summarily, given that ACL25–33 in the northern SCS is an effective indicator to trace vegetation change in the source area (He et al., 2008, 2017; Shintani et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2017; this study), the contrast between long-chain n-alkane and n-alkanol records in the study area could be attributed to aerobic degradation on relatively labile n-alkanols. This is further supported by a rough comparison between sedimentary records of long-chain n-alkanols and redox proxies, as shown below.

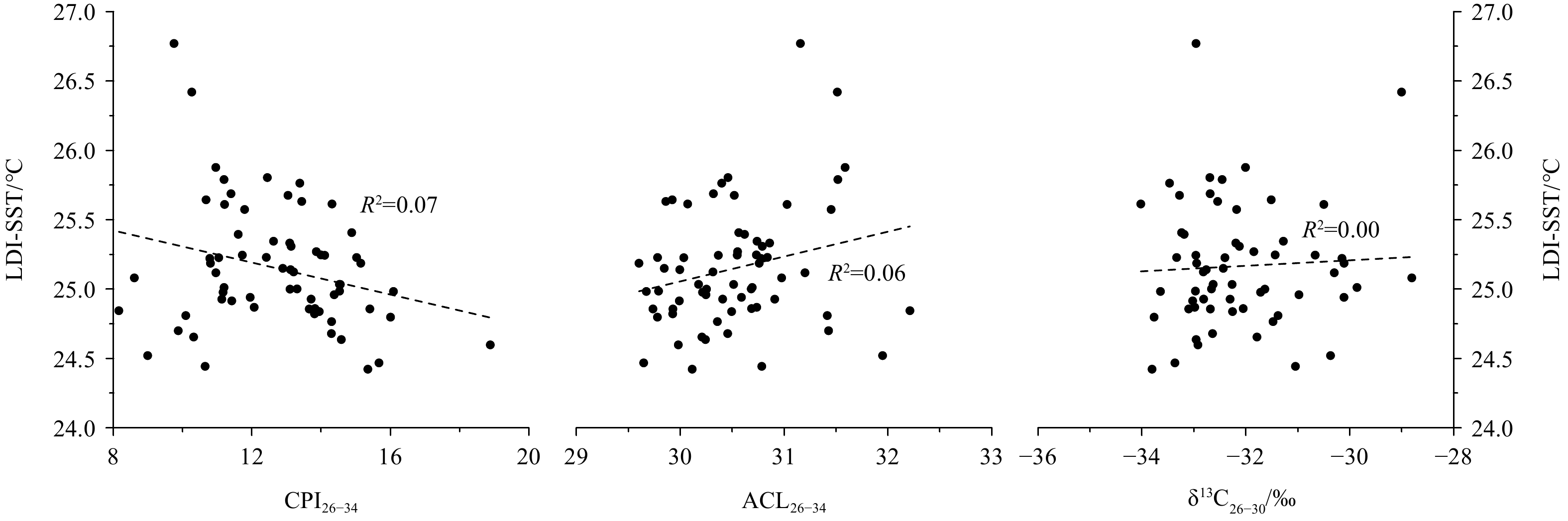

Two redox indices, namely cholestanol/(cholestanol+cholesterol) (C27Δ0/Δ0+Δ5) and U/Th content ratios, based on sterol biomarkers (Wakeham, 1989) and authigenic elements (Li et al., 2018), respectively, changes almost in parallel, especially before ~15 ka (Fig. 5). The relatively high values of both redox indices were indicative of lower redox potential at sediment-water interface, or in other words, less bottom water oxygenation and vice versa (Wakeham, 1989; Li et al., 2018). Therefore, downcore records of long-chain n-alkanols that changed negatively with two redox indices (Fig. 5) probably suggested the preferential losses of shorter chain homologues and more negative 12C compositions as a consequence of aerobic degradation during the interglacial period. In contrast, the lower redox potential, as well as relatively low sea level and strengthened winter monsoon would promote the source-to-sink transport of terrestrial-plant wax lipid into the study site, followed by a better preservation of terrestrial-original signals of long-chain n-alkanols in sediments during the LGM (Fig. 5). The temperature variability might play an insignificant role in controlling degradation of long-chain n-alkanols because they correlated irregularly with temperature records (Fig. 6), as was the case in the ZRE (Fig. 3).

The aerobic degradation of long-chain n-alkanols that obscured their response to original terrestrial signals might be a potential explanation for inconsistent trends compared to long-chain n-alkanes during the interglacial period. However, the discrepancy still occurred between the two n-alkyl lipid classes in respect to the terrestrial vegetation reconstruction during the LGM, when long-chain n-alkanols should have not experienced strong diagenetic alteration and could be a good preservation of terrestrial-original vegetation signals in sediments. Here, two major possibilities might be responsible for this discrepancy during the LGM.

Numerous palynological records in the northern SCS reveal extremely high pollen contents with a dominance of non-arboreal (dominated by Artemisia) and/or arboreal (dominated by Pinus) pollen representatives during the LGM (Sun and Li, 1999; Sun et al., 2000, 2003; Dai et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2017). The widespread and abundant occurrence of non-arboreal fossil pollen was likely indicative of these taxa growing on the adjacent exposed continental shelf (Sun and Li, 1999; Sun et al., 2000, 2003; Yu et al., 2017), whereas abundant arboreal pollen was likely derived from adjacent coastal area or China mainland (Sun and Li, 1999; Zheng and Li, 2000). As functionalized long-chain n-alkanols bias towards local vegetation signal, and contrastively n-alkanes integrate over a broader source region (Galy et al., 2011; Ponton et al., 2014; Hemingway et al., 2016), this might be a potential interpretation on the discrepancy between the two n-alkyl lipid classes. During the LGM, both leaf wax lipids and pollen of local vegetation likely dominated by C3 Artemisia herbs and/or C3 Pinus trees (Sun and Li, 1999; Sun et al., 2000, 2003; Yu et al., 2017) could be transported easily to the study area. Meanwhile, these local C3 plants-derived leaf wax lipids could be well preserved in sediments under lower redox potential and thus long-chain n-alcohol records could reflect a local signal of C3 plant expansion during the LGM. In contrast, relatively low sea level and strengthened winter monsoon would promote source-to-sink transport of long-chain n-alkanes over long distance from broader source area where C4 plants might expand, as proposed previously by Zhou et al. (2012), and distal C4 plant wax n-alkane signals, i.e., longer chain lengths and more positive δ13C compositions might have exceeded signals of local C3 plants during the LGM. This scenario could lead to sedimentary long-chain n-alkanes indicative of C4 plant expansion, thus producing contradictory history compared to long-chain n-alcohol records in the study area during the LGM.

In addition, large variations on compositions of different n-alkyl lipid classes among different species of C3/C4 plants (Diefendorf and Freimuth, 2017) might also play a part in modulating sedimentary long-chain n-alkanols and n-alkanes towards different vegetation signals. Extant plant wax n-alkyl lipid studies demonstrate that C3 plants on average (406 μg/g, n=163) produce more abundant long-chain n-alkanols than C4 plants (120 μg/g, n=39), whereas C4 plants on average (386 μg/g, n=93) produce almost equivalent long-chain n-alkanes compared to C3 plants (437 μg/g, n=288) (Conte et al., 2003; Chikaraishi et al., 2004; Rommerskirchen et al., 2006; Vogts et al., 2009; Bezabih et al., 2011; Diefendorf et al., 2011, 2015; Garcin et al., 2014; Bush and McInerney, 2015; Badewien et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018a) (Fig. 7). In this setting, extensively developed C3 plants, i.e., Artemisia herbs and/or Pinus trees (average 394 μg/g, n=5) around the northern SCS (Sun and Li, 1999; Sun et al., 2000, 2003; Zheng and Li, 2000; Yu et al., 2017), might produce abundant long-chain n-alkanols, while less developed local C4 plants might produce minor n-alkanols (Fig. 7), hence leading to sedimentary long-chain n-alkanols indicative of local C3 plant expansion during the LGM. In contrast, these local C3 plants, i.e., Artemisia herbs (average 240 μg/g, n=54) and/or Pinus trees (average 1 μg/g, n=5), might produce less long-chain n-alkanes than C4 plants (Fig. 7), thereby resulting in a bias in sedimentary long-chain n-alkanes not towards local C3 plant expansion during the LGM.

Sedimentary records of long-chain n-alkanols and n-alkanes in core sediments from the northern SCS were synchronously investigated to avoid problems and limitations using a single n-alkyl compound class in terms of terrestrial vegetation reconstruction. Our long-chain n-alkane data suggested that land vegetation in the source area was dominated by C3 plants during the interglacial period and more C4 plants developed during the LGM, which were generally consistent with previous studies in nearby cores. However, a prominent vegetation contrast occurred, if compared with long-chain n-alcohol records, which might be attributed to different factors. The diagenetic degradation of long-chain n-alkanols might be the main reason for the inconsistent trend and contradictory history compared with long-chain n-alkanes during the interglacial period. During the LGM, this discrepancy, however, might be ascribed to different responses of functionalized and non-functional n-alkyl lipid classes to vegetation source area and large variations among different species of C3/C4 plants that produce variable compositions of n-alkyl lipid classes. Further works on source-to-sink transport processes of long-chain n-alkanols are especially needed before these possibilities can be firmly established.

We thank the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey for providing Site 4B core sediment samples. Special thanks go to the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive comments that greatly improved the clarity and quality of the manuscript. We also acknowledge the support of SML311019006/311020006.

| [1] |

Badewien T, Vogts A, Rullkötter J. 2015. n-Alkane distribution and carbon stable isotope composition in leaf waxes of C3 and C4 plants from Angola. Organic Geochemistry, 89–90: 71–79

|

| [2] |

Bezabih M, Pellikaan W F, Tolera A, et al. 2011. Evaluation of n-alkanes and their carbon isotope enrichments (δ13C) as diet composition markers. Animal, 5: 57–66. doi: 10.1017/S1751731110001515

|

| [3] |

Bray E E, Evans E D. 1961. Distribution of n-paraffins as a clue to recognition of source beds. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 22(1): 2–15. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(61)90069-2

|

| [4] |

Bush R T, McInerney F A. 2015. Influence of temperature and C4 abundance on n-alkane chain length distributions across the central USA. Organic Geochemistry, 79: 65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2014.12.003

|

| [5] |

Chang Lin, Luo Yunli, Sun Xiangjun. 2013. Paleoenvironmental change base on a pollen record from deep sea core MD05–2904 from the northern South China Sea during the past 20000 years. Chinese Science Bulletin, 58(30): 3079–3087. doi: 10.1360/972012-786

|

| [6] |

Cheesbrough T M, Kolattukudy P E. 1984. Alkane biosynthesis by decarbonylation of aldehydes catalyzed by a particulate preparation from Pisum sativum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 81(21): 6613–6617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.21.6613

|

| [7] |

Chikaraishi Y, Naraoka H. 2007. δ13C and δD relationships among three n-alkyl compound classes (n-alkanoic acid, n-alkane and n-alkanol) of terrestrial higher plants. Organic Geochemistry, 38(2): 198–215. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.10.003

|

| [8] |

Chikaraishi Y, Naraoka H, Poulson S R. 2004. Carbon and hydrogen isotopic fractionation during lipid biosynthesis in a higher plant (Cryptomeria japonica). Phytochemistry, 65(3): 323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2003.12.003

|

| [9] |

China Vegetation Editorial Committee. 1980. Vegetation of China. Beijing: Science Press, 1–1375

|

| [10] |

Conte M H, Weber J C, Carlson P J, et al. 2003. Molecular and carbon isotopic composition of leaf wax in vegetation and aerosols in a northern prairie ecosystem. Oecologia, 135(1): 67–77. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-1157-4

|

| [11] |

Cranwell P A. 1981. Diagenesis of free and bound lipids in terrestrial detritus deposited in a lacustrine sediment. Organic Geochemistry, 3(3): 79–89. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(81)90002-4

|

| [12] |

Dai Lu, Hao Qinghe, Mao Limi. 2018. Morphological diversity of Quercus fossil pollen in the northern South China Sea during the last glacial maximum and its paleoclimatic implication. PLoS ONE, 13(10): e0205246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205246

|

| [13] |

Dai Lu, Weng Chengyu. 2015. Marine palynological record for tropical climate variations since the late last glacial maximum in the northern South China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 122: 153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.06.011

|

| [14] |

Dai Lu, Weng Chengyu, Lu Jun, et al. 2014. Pollen quantitative distribution in marine and fluvial surface sediments from the northern South China Sea: new insights into pollen transportation and deposition mechanisms. Quaternary International, 325: 136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2013.09.031

|

| [15] |

Dai Lu, Weng Chengyu, Mao Limi. 2015. Patterns of vegetation and climate change in the northern South China Sea during the last glaciation inferred from marine palynological records. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 440: 249–258

|

| [16] |

Damsté J S S, Rijpstra W I C, Reichart G J. 2002. The influence of oxic degradation on the sedimentary biomarker record II. Evidence from Arabian Sea sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 66(15): 2737–2754. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(02)00865-7

|

| [17] |

Diefendorf A F, Freeman K H, Wing S L, et al. 2011. Production of n-alkyl lipids in living plants and implications for the geologic past. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 75(23): 7472–7485. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.09.028

|

| [18] |

Diefendorf A F, Freimuth E J. 2017. Extracting the most from terrestrial plant-derived n-alkyl lipids and their carbon isotopes from the sedimentary record: a review. Organic Geochemistry, 103: 1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2016.10.016

|

| [19] |

Diefendorf A F, Leslie A B, Wing S L. 2015. Leaf wax composition and carbon isotopes vary among major conifer groups. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 170: 145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.08.018

|

| [20] |

Eglinton G, Hamilton R J. 1967. Leaf epicuticular waxes: the waxy outer surfaces of most plants display a wide diversity of fine structure and chemical constituents. Science, 156(3780): 1322–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3780.1322

|

| [21] |

Galy V, Eglinton T, France-Lanord C, et al. 2011. The provenance of vegetation and environmental signatures encoded in vascular plant biomarkers carried by the Ganges-Brahmaputra Rivers. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 304(1–2): 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpgl.2011.02.003

|

| [22] |

Garcin Y, Schefuß E, Schwab V F, et al. 2014. Reconstructing C3 and C4 vegetation cover using n-alkane carbon isotope ratios in recent lake sediments from Cameroon, Western Central Africa. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 142: 482–500. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.07.004

|

| [23] |

Guo Wei. 2015. Source and biogeochemical properties of oragnic carbon in water column and sediments of Pearl River Estuary (in Chinese)[dissertation]. Beijing: University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1–146

|

| [24] |

Guo Wei, Jia Guodong, Ye Feng, et al. 2019. Lipid biomarkers in suspended particulate matter and surface sediments in the Pearl River Estuary, a subtropical estuary in southern China. Science of the Total Environment, 646: 416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.159

|

| [25] |

Guo Wei, Ye Feng, Xu Shendong, et al. 2015. Seasonal variation in sources and processing of particulate organic carbon in the Pearl River Estuary, South China. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 167: 540–548

|

| [26] |

Hartnett H E, Keil R G, Hedges J I, et al. 1998. Influence of oxygen exposure time on organic carbon preservation in continental margin sediments. Nature, 391(6667): 572–575. doi: 10.1038/35351

|

| [27] |

He Juan, Jia Guodong, Li Li, et al. 2017. Differential timing of C4 plant decline and grassland retreat during the penultimate deglaciation. Global and Planetary Change, 156: 26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2017.08.001

|

| [28] |

He Juan, Zhao Meixun, Li Li, et al. 2008. Sea surface temperature and terrestrial biomarker records of the last 260 ka of core MD05–2904 from the northern South China Sea. Chinese Science Bulletin, 53(15): 2376–2384

|

| [29] |

Hemingway J D, Schefuß E, Dinga B J, et al. 2016. Multiple plant-wax compounds record differential sources and ecosystem structure in large river catchments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 184: 20–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2016.04.003

|

| [30] |

Hoefs M J L, Rijpstra W I C, Damsté J S S. 2002. The influence of oxic degradation on the sedimentary biomarker record I: evidence from Madeira Abyssal Plain turbidites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 66(15): 2719–2735. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(02)00864-5

|

| [31] |

Hu Jianfang, Peng Ping’an, Chivas A R. 2009. Molecular biomarker evidence of origins and transport of organic matter in sediments of the Pearl River Estuary and adjacent South China Sea. Applied Geochemistry, 24(9): 1666–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2009.04.035

|

| [32] |

Hu Jianfang, Peng Ping’an, Fang Dianyong, et al. 2003. No aridity in Sunda Land during the Last Glaciation: evidence from molecular-isotopic stratigraphy of long-chain n-alkanes. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 201(3–4): 269–281

|

| [33] |

Huang Enqing, Tian Jun. 2012. Sea-level rises at Heinrich stadials of early Marine Isotope Stage 3: evidence of terrigenous n-alkane input in the southern South China Sea. Global and Planetary Change, 94–95: 1–12

|

| [34] |

Lambeck K, Rouby H, Purcell A, et al. 2014. Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(43): 15296–15303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411762111

|

| [35] |

Li Li, Li Qianyu, Li Jianru, et al. 2015. A hydroclimate regime shift around 270 ka in the western tropical Pacific inferred from a late Quaternary n-alkane chain-length record. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 427: 79–88

|

| [36] |

Li Li, Li Qianyu, Tian Jun, et al. 2013. Low latitude hydro-climatic changes during the Plio-Pleistocene: evidence from high resolution alkane records in the southern South China Sea. Quaternary Science Reviews, 78: 209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.08.007

|

| [37] |

Li Gang, Rashid H, Zhong Lifeng, et al. 2018. Changes in deep water oxygenation of the South China Sea since the last glacial period. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(17): 9058–9066. doi: 10.1029/2018GL078568

|

| [38] |

Lin Dacheng, Chen Minte, Yamamoto M, et al. 2017. Hydrographic variability in the northern South China Sea over the past 45, 000 years: new insights based on temperature reconstructions by

|

| [39] |

Liu Fang, Chang Xiaohong, Liao Zewen, et al. 2019. n-Alkanes as indicators of climate and vegetation variations since the last glacial period recorded in a sediment core from the northeastern South China Sea (SCS). Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 171: 134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2018.09.018

|

| [40] |

Meyers P A, Eadie B J. 1993. Sources, degradation and recycling of organic matter associated with sinking particles in Lake Michigan. Organic Geochemistry, 20(1): 47–56. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(93)90080-U

|

| [41] |

Meyers P A, Ishiwatari R. 1993. Lacustrine organic geochemistry—an overview of indicators of organic matter sources and diagenesis in lake sediments. Organic Geochemistry, 20(7): 867–900. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(93)90100-P

|

| [42] |

Mortazavi B, Conte M H, Chanton J P, et al. 2012. Variability in the carbon isotopic composition of foliage carbon pools (soluble carbohydrates, waxes) and respiration fluxes in southeastern U. S. pine forests. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 117(G2): G02009

|

| [43] |

Müller P J, Suess E. 1979. Productivity, sedimentation rate, and sedimentary organic matter in the oceans—I. Organic carbon preservation. Deep-Sea Research Part A: Oceanographic Research Papers, 26(12): 1347–1362

|

| [44] |

Pelejero C. 2003. Terrigenous n-alkane input in the South China Sea: high-resolution records and surface sediments. Chemical Geology, 200(1−2): 89–103. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(03)00164-5

|

| [45] |

Ponton C, West A J, Feakins S J, et al. 2014. Leaf wax biomarkers in transit record river catchment composition. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(18): 6420–6427. doi: 10.1002/2014GL061328

|

| [46] |

Post-Beittenmiller D. 1996. Biochemistry and molecular biology of wax production in plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology, 47: 405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.405

|

| [47] |

Rommerskirchen F, Plader A, Eglinton G, et al. 2006. Chemotaxonomic significance of distribution and stable carbon isotopic composition of long-chain alkanes and alkan-1-ols in C4 grass waxes. Organic Geochemistry, 37(10): 1303–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2005.12.013

|

| [48] |

Shintani T, Yamamoto M, Chen Minte. 2011. Paleoenvironmental changes in the northern South China Sea over the past 28, 000 years: a study of TEX86-derived sea surface temperatures and terrestrial biomarkers. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 40(6): 1221–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2010.09.013

|

| [49] |

Strong D J, Flecker R, Valdes P J, et al. 2012. Organic matter distribution in the modern sediments of the Pearl River Estuary. Organic Geochemistry, 49: 68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2012.04.011

|

| [50] |

Strong D, Flecker R, Valdes P J, et al. 2013. A new regional, mid-Holocene palaeoprecipitation signal of the Asian Summer Monsoon. Quaternary Science Reviews, 78: 65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.07.034

|

| [51] |

Sun Xiangjun, Li Xun. 1999. A pollen record of the last 37 ka in deep sea core 17940 from the northern slope of the South China Sea. Marine Geology, 156(1–4): 227–244. doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00181-9

|

| [52] |

Sun Xiangjun, Li Xu, Luo Yunli, et al. 2000. The vegetation and climate at the last glaciation on the emerged continental shelf of the South China Sea. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 160(3–4): 301–316

|

| [53] |

Sun Xiangjun, Luo Yunli, Huang Fei, et al. 2003. Deep-sea pollen from the South China Sea: pleistocene indicators of East Asian monsoon. Marine Geology, 201(1–3): 97–118. doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(03)00211-1

|

| [54] |

Sun Mingyi, Wakeham S G. 1994. Molecular evidence for degradation and preservation of organic matter in the anoxic Black Sea Basin. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 58(16): 3395–3406. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(94)90094-9

|

| [55] |

Sun Mingyi, Wakeham S G, Lee C. 1997. Rates and mechanisms of fatty acid degradation in oxic and anoxic coastal marine sediments of Long Island Sound, New York, USA. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 61(2): 341–355. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(96)00315-8

|

| [56] |

van Dongen B E, Zencak Z, Gustafsson Ö. 2008. Differential transport and degradation of bulk organic carbon and specific terrestrial biomarkers in the surface waters of a sub-Arctic brackish bay mixing zone. Marine Chemistry, 112(3–4): 203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2008.08.002

|

| [57] |

Vogts A, Moossen H, Rommerskirchen F, et al. 2009. Distribution patterns and stable carbon isotopic composition of alkanes and alkan-1-ols from plant waxes of African rain forest and savanna C3 species. Organic Geochemistry, 40(10): 1037–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2009.07.011

|

| [58] |

Wakeham S G. 1989. Reduction of stenols to stanols in particulate matter at oxic–anoxic boundaries in sea water. Nature, 342(6251): 787–790. doi: 10.1038/342787a0

|

| [59] |

Wakeham S G, Amann R, Freeman K H, et al. 2007. Microbial ecology of the stratified water column of the Black Sea as revealed by a comprehensive biomarker study. Organic Geochemistry, 38(12): 2070–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2007.08.003

|

| [60] |

Wang Jia, Xu Yunping, Zhou Liping, et al. 2018a. Disentangling temperature effects on leaf wax n-alkane traits and carbon isotopic composition from phylogeny and precipitation. Organic Geochemistry, 126: 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.10.008

|

| [61] |

Wang Mengyuan, Zheng Zhuo, Gao Quanzhou, et al. 2018b. The environmental conditions of MIS5 in the northern South China Sea, revealed by n-alkanes indices and alkenones from a 39 m-long sediment sequence. Quaternary International, 479: 70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.08.026

|

| [62] |

Xu Shendong, Zhang Jie, Wang Xianxu, et al. 2016. Catchment environmental change over the 20th Century recorded by sedimentary leaf wax n-alkane δ13C off the Pearl River Estuary. Science China: Earth Sciences, 59(5): 975–980. doi: 10.1007/s11430-015-5206-3

|

| [63] |

Yu Shaohua, Zheng Zhuo, Chen Fang, et al. 2017. A last glacial and deglacial pollen record from the northern South China Sea: new insight into coastal-shelf paleoenvironment. Quaternary Science Reviews, 157: 114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.12.012

|

| [64] |

Zheng Zhuo, Li Qianyu. 2000. Vegetation, climate, and sea level in the past 55, 000 years, Hanjiang Delta, southeastern China. Quaternary Research, 5(3): 330–340

|

| [65] |

Zhou Bin, Zheng Hongbo, Yang Wenguang, et al. 2012. Climate and vegetation variations since the LGM recorded by biomarkers from a sediment core in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Quaternary Science, 27(9): 948–955. doi: 10.1002/jqs.2588

|

| [66] |

Zhu Xiaowei, Mao Shengyi, Sun Yongge, et al. 2018. Organic molecular evidence of seafloor hydrocarbon seepage in sedimentary intervals down a core in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 168: 155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2018.11.009

|

| [67] |

Zhu Xiaowei, Mao Shengyi, Sun Yongge, et al. 2019. Long chain diol index (LDI) as a potential measure to estimate annual mean sea surface temperature in the northern South China Sea. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 221: 1–7

|

| [68] |

Zhu Xiaowei, Mao Shengyi, Wu Nengyou, et al. 2014. Molecular and stable carbon isotopic compositions of saturated fatty acids within one sedimentary profile in the Shenhu, northern South China Sea: source implications. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 92: 262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2013.12.011

|

| [69] |

Zhu Xiaowei, Mao Shengyi, Wu Nengyou, et al. 2016. Detection and indication of 1, 3, 4-C27–29 triol in the sediment of northern South China Sea. Science China: Earth Sciences, 59(6): 1187–1194. doi: 10.1007/s11430-016-5270-3

|

| 1. | Xiangle Jiang, Wenjin Zhu, Yang Zhang, et al. Changes and factors of thermal discharge from 2013 to 2023: A case study of the Tianwan nuclear power plant. Ecological Indicators, 2025, 170: 112986. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112986 |