| Citation: | Lingfang Fan, Min Chen, Zifei Yang, Minfang Zheng, Yusheng Qiu. Alleviated photoinhibition on nitrification in the Indian Sector of the Southern Ocean[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2024, 43(7): 52-69. doi: 10.1007/s13131-024-2379-7 |

The Southern Ocean plays a crucial role in global carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation through the primary production of phytoplankton (DeVries, 2014; Gruber et al., 2023). However, nitrification releases N2O, a potent greenhouse gas that counteracts the carbon sink effect in the ocean (Law and Ling, 2001). In classical nitrification, ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) convert ammonium into nitrite, which is subsequently oxidized to nitrate by nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB). Their activity in the euphotic zone directly influences the composition of inorganic nitrogen and the production of regenerative nitrate for phytoplankton assimilation, thereby affecting the strength of marine biological pumps. Elucidating the magnitude and environmental regulation of nitrification rates is critical to understanding carbon and nitrogen cycles in the Southern Ocean fully.

Studies on nitrification in the Southern Ocean are limited (summarized in Table S1) and focus on areas north of 60°S (Olson, 1981; Bianchi et al., 1997; Mdutyana et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Raes et al., 2020), in the Antarctic coastal waters (Tolar et al., 2016b; Alcamán-Arias et al., 2022), and in naturally iron-fertilized areas (Cavagna et al., 2015; Fripiat et al., 2015), which are not representative of the open Southern Ocean. Owing to diverse research objectives and early technical constraints, studies have mainly focused on the different steps of nitrification, such as the total nitrification rate (NR, oxidation of

The debate on light inhibition of nitrification continues. The consistent finding of higher nitrification rates at the base of the euphotic zone has led to a growing acceptance that light suppression is responsible for the reduced nitrification in the epipelagic zone (Shiozaki et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2020), although whether this photoinhibition to nitrifiers is direct (Qin et al., 2014) or indirect via photochemical production of H2O2 (Kim et al., 2016) remains to be resolved (Hollibaugh, 2017). The notion of photoinhibition is further supported by the potential competition of phytoplankton for

Nitrification is typically modeled as a linear function of the ambient ammonium (

As important areas in East Antarctica, the Cosmonaut and Cooperation seas are located south of the Polar Front [PF, the center of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)] and serve as natural laboratories for nitrification. The region is characterized by the upwelling of Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW), which is an important source of nutrients, specifically iron, from the deep ocean to the surface (Tagliabue et al., 2012). Moreover, the Southern Boundary of the upper CDW (SB front) in the Cosmonaut and Cooperation seas is closest to the Antarctic shore. High nitrification rates of up to 400 nmol/(L·d) (in terms of N) have been observed in well-known upwelling zones of low-latitude oligotrophic seas (Rees et al., 2006; Fernández et al., 2009; Beman et al., 2012; Fernández and Farías, 2012). These high rates are often attributed to enhanced primary production spurred by nutrients provided by upwelling. However, for the

To uncover the biogeochemical mechanisms driving nitrification and their role in the dynamic Southern Ocean, we conducted nitrification and substrate kinetic experiments in both light and dark incubations using the 15N tracer method in the Cosmonaut and Cooperation seas south of 60°S. Our study aimed to (1) assess the extent and trend of light inhibition on summer nitrification; (2) examine the response of substrate kinetics and the interaction between light inhibition and substrate supply to substrate affinity (α); and (3) explore the regulatory role and distinct mechanism of CDW upwelling in nitrification. We propose that in the Southern Ocean during summer, nitrification rates are enhanced by alleviated photoinhibition through the coupling of ammonium availability and upwelling events.

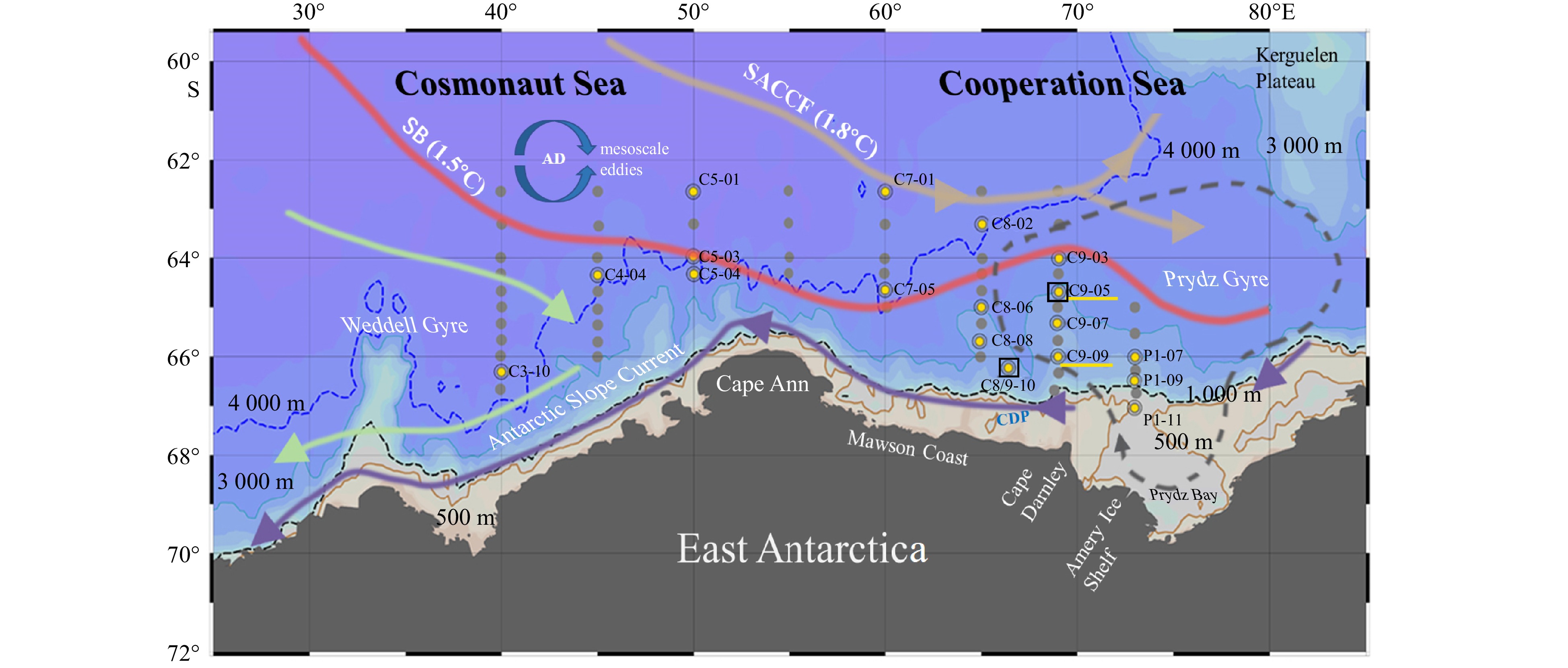

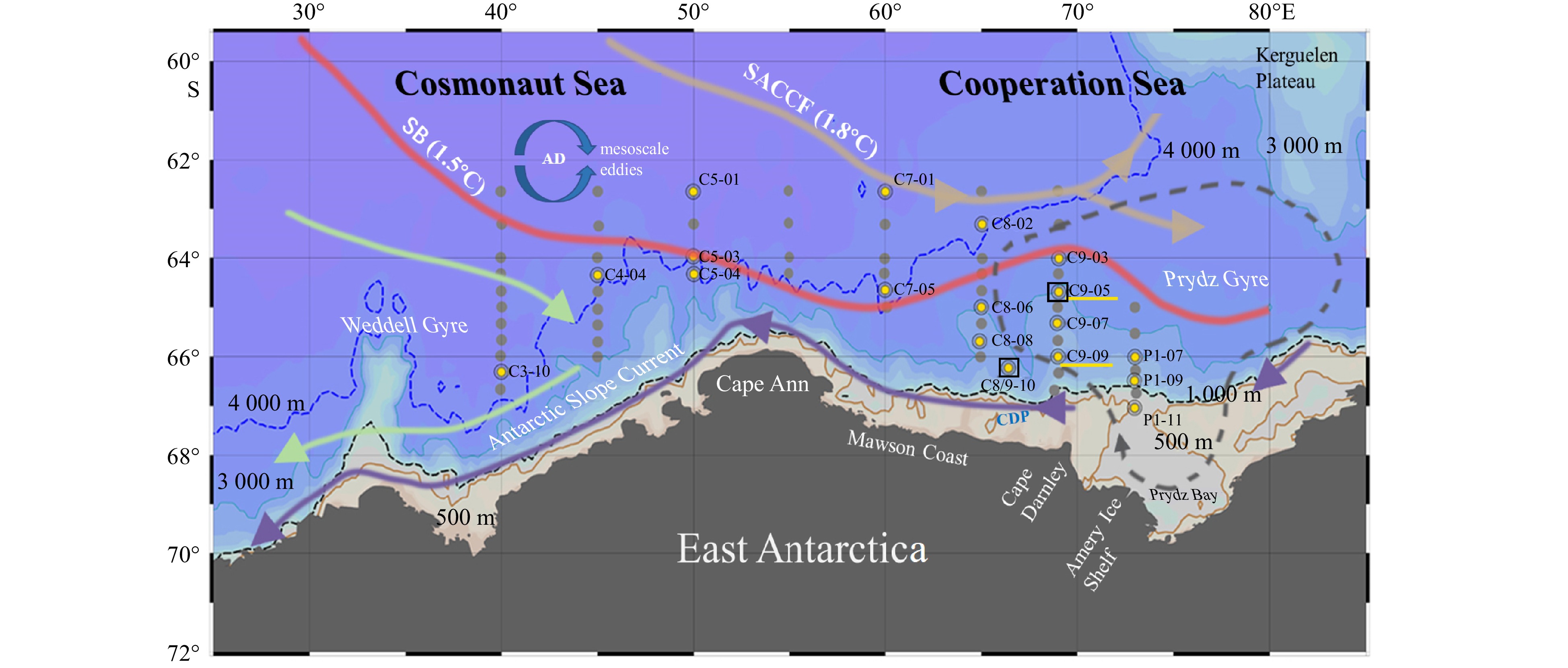

Seawater samples were collected from the Cosmonaut and Cooperation seas in the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean aboard R/V Xuelong 2. The sampling time was from December 4, 2019, to January 7, 2020, during the 36th China Antarctic Research Expedition (Fig. 1). Detailed descriptions of sampling locations, procedures for oceanographic measurements for temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen (DO), dissolved inorganic nitrogen (

The in-situ light NR (denoted as NRin situ) in the water column above 500 m at 18 sites was measured using a 15N-spike incubation under simulated field conditions (yellow dots in Fig. 1). Seawater samples collected from 100%, 50%, 10%, 1%, and 0.1% surface photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) depths and two deep layers in darkness (corresponding to depths of 0 m, ~25 m, ~50 m, ~100 m, ~200 m, 300 m, and 500 m) were pre-filtered through a 200 μm pore size sieve to remove macrozooplankton. The PAR at each depth was determined from the light transmission using a standard Secchi-disc with a diameter of 30 cm, assuming that the light intensity decays exponentially with depth. After transferring the samples to 500 mL acid-washed, sample-rinsed clear polycarbonate bottles, 15N-labeled (NH4)2SO4 tracer (15N abundance > 98% (atomic percent), Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to obtain a final 15

The NRs of the samples in darkness between 0 m and 200 m were also determined (denoted as NRdark). After the samples were transferred to bottles and the same amount of 15N tracer was added, the bottles were covered with a completely opaque black cloth and incubated under simulated field conditions. The incubation of NRin situ at depths of 300 m and 500 m was identical to that of NRdark. No significant correlation was observed between NRdark and

Time-series experiments in situ and under dark conditions were performed at Sites C9-05 and C8/09-10 to verify the linear increase in δ15

δ15N in

The NR was calculated using the following equation (Tolar et al., 2016b):

| $$ {\mathrm{NR}}=\frac{{C}_{\mathrm{t}}\cdot {n}_{\mathrm{t}}-{C}_{0}\cdot {n}_{0}}{T\cdot {f}^{15}}, $$ | (1) |

where NR represents the total nitrification rate [nmol/(L·d), in terms of N]; Ct and C0 are the

PI was used to evaluate the effect of light intensity on the NR and was defined as follows:

| $$ \mathrm{P}\mathrm{I}=\frac{{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{k}}}{{\mathrm{N}\mathrm{R}}_{in\;situ}}. $$ | (2) |

PI values greater and less than 1 represent negative and positive light effects, respectively. The greater the deviation of the PI value from 1, the higher the photosensitivity of the nitrifying microorganisms.

The Michaelis-Menten (M-M) equation (MacIsaac and Dugdale, 1969) was used to establish the relationship between the PI and PAR (%), from which the maximum photosensitivity index (PImax) and half-saturation constant of light intensity (KL) were estimated as follows:

| $$ \mathrm{PI}=\frac{{\mathrm{PI}}_{\mathrm{max}}\cdot \mathrm{PAR}}{{K}_{\mathrm{L}}+\mathrm{PAR}}. $$ | (3) |

The estimated PImax and KL values were used to reflect the light tolerance and photosensitivity of the nitrifiers. Furthermore, the light threshold can be derived from the M-M curve at PI = 1.

The following equation was used to quantify the photoinhibition effect at each depth:

| $$ {\mathrm{Light}}\;{\mathrm{inhibition}}=\frac{({{\mathrm{NR}}}_{{\mathrm{dark}}}-{{\mathrm{NR}}}_{in\; situ})}{{{\mathrm{NR}}}_{{\mathrm{dark}}}}\times 100\%. $$ | (4) |

The profile of light inhibition (%) reflects the variation in the extent of photoinhibition on nitrification.

The M-M equation (MacIsaac and Dugdale, 1969) was used to estimate the substrate kinetic parameters from the data obtained in situ and the dark in

| $$ \mathrm{N}\mathrm{R}=\frac{{V}_{\mathrm{m}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{x}}\cdot S}{{K}_{\mathrm{m}}+S} ,$$ | (5) |

where NR represents the measured nitrification rate [nmol/(L·d), in terms of N], Vmax is the maximum rate at the substrate saturation concentration [nmol/(L·d), in terms of N], Km is the half-saturation constant of the substrate at (1/2) × Vmax (nmol/L), and S is the total

The substrate affinity coefficient (α) is a good indicator of competitiveness for the substrate and can be estimated from the initial slope of the M-M curve at low substrate concentrations (Healey, 1980; Martens-Habbena et al., 2009):

| $$ \mathrm{\alpha }=\frac{{V}_{\mathrm{m}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{x}}\cdot 24}{{K}_{\mathrm{m}}}, $$ | (6) |

where α (d−1) is substrate affinity coefficient (×10−3 h−1), and Vmax and Km are derived from Eq. (5). This method was used to calculate α values for nitrification in the global ocean, as detailed in the Dataset S1.

Here, we assumed that nitrification occurs at different rates during a 12 h light and dark cycle, and the nitrification-driven

| $$\begin{split} T=&\frac{S}{12\cdot {V}_{{\mathrm{L}}}+12\cdot {V}_{{\mathrm{D}}}}=\frac{S}{12\cdot \left({\alpha }_{{\mathrm{L}}}\cdot S\right)+12\cdot ({\alpha }_{\mathrm{D}}\cdot S)}=\\ &\frac{1}{12\cdot ({{\alpha }}_{{\mathrm{L}}}+{{\alpha }}_{\mathrm{D}})}, \end{split}$$ | (7) |

where S represents the substrate concentration (nmol/L), and the subscripts L and D represent Vmax [nmol/(L·d), in terms of N] or α (h−1) under light and dark conditions, respectively. This method incorporated the influence of light on substrate turnover, better than previous approaches that relied solely on dividing the

To assess the relationship between upwelling and NRs, we employed several indicators reflecting upwelling strength, including potential temperature (θ), salinity, and nitrate anomalies. These indicators were derived by identifying the positive anomalies for each parameter referenced to the mean value at 100 m for the open ocean sites on each meridional transect (Williams et al., 2010). A more pronounced positive anomaly indicated stronger upwelling, whereas a negative anomaly indicated no upwelling.

The comprehensive characteristics of water masses are depicted in Fig. 2a and explained in the Text S1. In water masses above 500 m, Winter Residual Water (WW) and Thermocline Water (TCW) contributed to the highest NRin situ, each averaging approximately 30 nmol/(L·d) (in terms of N) with substantial variability (Fig. 2b). In contrast, the mean NRin situ in Antarctic Surface Water (AASW) situated above the WW was reduced by a factor of 8.8, despite the generally high

Regionally, the maximum NR along each meridional section in the open areas appeared near the SB front. The distribution of NR in Section SB (Fig. S2a) showed that the sites with higher NRs correspond to the rising of deep nitrate, such as Sites C8-06 and C9-03 in the Cooperation Sea and Site C4-04 in the Cosmonaut Sea. The maximum NRin situ at these sites ranged between 83.3 nmol/(L·d) and 118.7 nmol/(L·d) (in terms of N), corresponding to NRdark between 101.8 nmol/(L·d) and 217.8 nmol/(L·d) (in terms of N) (Figs S2e−g). The lowest NR occurred at Section C7 northeast of Cape Ann, where

We investigated the effect of substrate concentration on NRs in situ and under dark conditions by adding different amounts of isotope-labeled substrates to samples at different depths at two sites (C9-09 and C9-05). In each case, both NRin situ and NRdark increased with the total ammonium (15N tracer plus

Nitrification was photoinhibited at our study sites. The spatial distribution of the average NRin situ and NRdark at each site is shown in Fig. 5a. Site P1 values, obtained by comparing site average-NR in darkness and in situ light [Eq. (2)], ranged from 1.1 to 2.3, with an average of 1.6 ± 0.4. Culture experiments have suggested that photoinhibition results from light-induced damage to electron transport systems and ammonia monooxygenase (AMO) in nitrifying microorganisms such as AOB, while this physiological mechanism in AOA remains unclear (Lu et al., 2020). Moreover, AOA is susceptible to indirect photoinhibition in surface water (Kim et al., 2016; Tolar et al., 2016a) with H2O2 toxicity threshold ranging from 10 nmol/L to 300 nmol/L (Tolar et al., 2016a; Horak et al., 2018). We cannot differentiate the relative contributions of direct and indirect photoinhibition on nitrification, where AOA dominates in the Southern Ocean (Kalanetra et al., 2009; Sow et al., 2022). However, reported H2O2 concentrations in upper waters near our study area are low at 5−32 nmol/L (Sarthou et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2022). Nitrification may experience a more fundamental inhibition directly from light irradiation rather than H2O2 toxicity in open ocean regimes (Horak et al., 2018), which needs to be confirmed. In our study, significant differences in light and dark NR were observed at light intensities above 1% PAR (p =

The photoinhibition of nitrification follows an exponential decay pattern with depth. The percentage of nitrification inhibited by light at each depth [Eq. (4)] is shown in Fig. 5b as blue horizontal bars. The strongest photoinhibition (ca. 72%) occurred at 0−25 m (100%−50% PAR); however, most NRin situ in this depth interval remained above the detection limit with a mean value of (2.6 ± 3.1) nmol/(L·d) (in terms of N). For NRdark in the 0−25 m depth interval, most NRdark did not increase significantly [mean (5.2 ± 4.9) nmol/(L·d), in terms of N] compared with that of NRin situ, despite having the highest [

NR and light inhibition followed a predictable pattern, and the impact of diurnal phytoplankton competition for

However, the light threshold for nitrification remains poorly understood, with the reported threshold at about 0.22%−0.54% PAR in the Arctic shelf (Shiozaki et al., 2019) and between 0.2% and 2% PAR in coastal Southern California (Olson, 1981). Most studies have only described the PAR values at which the nitrification peaks, with early studies at 5%−10% PAR (Ward, 2011a) and recent reports at approximately 1% PAR (Peng et al., 2018; Clark et al., 2022). We treated the PAR as a variable and calculated the average PI (PIavg) for each PAR group. The relationship between PIavg and PAR followed an M-M curve with a maximum PI (PImax) of 3.4 ± 0.6 and a light saturation constant (KL) of 1.3% ± 1.4% PAR [Eq. (3), Fig. S4, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.54]. The PImax value exceeds the slope of the linear fit between NRin situ and NRdark by 1.22. These results may indicate two things. (1) The effects of photoinhibition on nitrification, in the context of global climate warming and reduced sea ice, follow a first-order reaction, as observed in the Arctic (Shiozaki et al., 2019); and (2) the photosensitivity of nitrification may be saturated in the more distant future. Nitrifying AOAs are diverse (Francis et al., 2005; Santoro et al., 2019), and some members may have significant physiological diversity, including light tolerance (Kalanetra et al., 2009; Martens-Habbena et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2014b) and unique genetic traits associated with reduced photodamage (Luo et al., 2014). Specifically, a high abundance of ammonia-oxidizing organisms in the epipelagic zone accounts for 45%−100% of the prokaryotes in the Southern Ocean (Alonso-Sáez et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2014; Raes et al., 2018, 2020; Sow et al., 2022), with high transcription levels of AOA, AOB, and extremely high NRin situ [68.3 nmol/(L·d), in terms of N] observed in Antarctic coastal surface waters in summer, possibly due to metabolic light adaptation of nitrifying microorganisms (Alcamán-Arias et al., 2022).

The light threshold for nitrification in our study area obtained from the M-M curve (when PI = 1) was 0.53% PAR, which falls within the reported range of 0.2% to 2% PAR (Olson, 1981; Shiozaki et al., 2019). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify light-sensitive parameters of summer nitrification in the Southern Ocean, including PImax, KL, and light threshold, based on field measurements. As surface light intensity and its attenuation with depth vary seasonally and regionally, future studies will benefit from the relationship between PI and PAR (or absolute light intensity) established by paired light-dark NR experiments. This approach allows for a more intuitive comparison of the spatiotemporal variability in light inhibition and provides insights into future trends in photoinhibition tolerance.

Ammonium is a crucial substrate for nitrification and an energy source for nitrifiers. We found no correlation between NR and [

Nitrification is regulated by both the substrate and light; however, light inhibition becomes the primary limiting factor for summer nitrification at local

The primary role of light inhibition was further validated by substrate kinetics experiments. For the 25 m sample (50% PAR) at Site C9-09, NRin situ did not fit the M-M curve, showed minimal rate response and persistent unsaturation (red hollow squares in Fig. 4a) and had the highest PI at low tracer addition (pink solid squares in Fig. 7b). The linear fit indicated a substrate threshold of 305 nmol/L. Notably, Vmax under dark conditions was restored to fit the M-M curve despite being the shallowest of the four depths in the substrate kinetic experiment. Accordingly, we suggest that nitrifier communities need a substrate threshold higher than the survival threshold (10 nmol/L, Martens-Habbena et al., 2009) to cope with intense light-induced stress and perform nitrification under photoinhibition greater than 50% PAR. In contrast, the strong response of NRlight at 60 m from Site C9-05 may have benefited from the reduction in photoinhibition at 10% PAR, thereby allowing a greater proportion of the substrate to be used directly for nitrification.

Changes of photosensitivity parameters and NRs in substrate enrichment experiments suggest enhanced photoinactivation under low-substrate conditions and buffered photodamage under high-substrate conditions, even at the maximum PAR (Dataset S3). Specifically, across a tracer gradient from 34 nmol/L to

Currently, substrate kinetic parameters for nitrification have been obtained primarily from dark incubations in limited marine environments, with most studies focusing on the Northern Hemisphere. More attention was given to comparing the values of Km and/or Vmax with their influencing factors. This comparison is of limited significance because the data are from different depths and lack normalization for nitrifying microbial abundance (Smith et al., 2014a; Mdutyana et al., 2022b). In addition, a smaller Km (generally considered to indicate a higher substrate affinity) does not necessarily correspond to a larger Vmax value, and vice versa (Dataset S1). The reported Vmax values for NR or

The αdark and αlight values at Sites C9-09 and C9-05 ranged from (0.8 × 10−3) h−1 to (9.9 × 10−3) h−1 and (0.2 × 10−3) h−1 to (7.6 × 10−3) h−1, respectively (Fig. 8a). The reported αdark changed between (0.05 × 10−3) h−1 and (50.7 × 10−3) h−1 (Horak et al., 2013; Newell et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2016; Wan et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020; Mdutyana et al., 2022b) and the reported αlight changed between (0.01 × 10−3) h−1 and (1.5 × 10−3) h−1 (Xu et al., 2019). These α values cover differences in

Light is the first factor affecting the substrate kinetics of nitrification. In this study, we found that α values increased with depth (PAR decay) and were higher under dark conditions. The deep αlight and αdark values were 2.2 times to 17.3 times and 1.4 times to 7.0 times than that of the shallower layer at the same site, respectively. In contrast, at the same depth, αdark was 1.3 times to 3.9 times higher than αlight (Fig. 8a). A negative correlation was observed between α value and PAR (slope = −0.12, R2 = 0.66, p =

The second factor affecting the substrate kinetics of nitrification is substrate concentration. We found a negative correlation between α and [

In addition, the αdark value seems to have a latitude effect, decreasing from low to high latitude seas (Fig. 8e), with a larger absolute slope value in the linear fit between αdark and latitude in the Northern Hemisphere (0.89) than the Southern Hemisphere (0.56). This latitude effect may be related to changes in temperature, and the composition of the nitrifying microbial community, which deserves further study.

Light and substrate availability coregulate NR and α values, therefore the estimation of

In summary, we describe patterns of α variation in the global ocean, confirm that αdark is also affected by the residual effects of high PAR inhibition, and reveal the survival strategies of nitrifying microorganisms in response to photoinhibition and substrate limitation. Conducting experiments under light and dark conditions simultaneously is necessary to reveal the substrate kinetics of nitrification more accurately.

Our results showed that at 100 m, the spatial variation of NRin situ and NRdark fits well with the distribution of upwelling indicators such as anomalies of nitrate, potential temperature (θ), and salinity (Figs 9a−e). The linear positive correlation between NRin situ, NRdark, and nitrate anomaly at 100 m (in situ: slope = 5.1, R2 = 0.35, p =

Two main hypotheses have been proposed to explain the enhancement of nitrification via upwelling in oligotrophic seas. First, upwelling or mesoscale eddies provide nutrients and promote the primary production and regeneration of

The CDW is a hotspot for archaeal richness and diversity. In the Amundsen and Ross seas, the relative abundance of Marine Group I (MGI) with ammonia oxidation function in the CDW was 3.2−30.7 times higher than that in the upper waters (Alonso-Sáez et al., 2011). The diversity of Nitrosopumilus (represented by SCMI-AOA) in the Indian Ocean sector (48°−65°S, 71°−99°E), mesopelagic and abyssal in summer was higher than that on the surface (<200 m) (Sow et al., 2022). Second, the transport of CDW allows the dispersal of archaea to Antarctic shelves and other oceans (Murray et al., 1999; Alonso-Sáez et al., 2011; Sintes et al., 2016). The higher NRs measured in this study appeared in Sections C8, C9, and P1, which were areas where CDW rose and mixed with dense shelf water to form Antarctic Bottom Water (Gao et al., 2022), reflecting the promotion effect of rising CDW on nitrification. The highest deep NRdark was 141.7 nmol/(L·d) (in terms of N) at 200 m from slope Site P1-09 (Fig. 3f), which was comparable to the maximum

Higher DFe provided by the CDW upwelling may alleviate the limitation of iron on nitrification in the upper water. The key enzymes in nitrifying microorganisms have high iron requirements (Arp et al., 2002; Lücker et al., 2010; Shafiee et al., 2019). The concentration of DFe in the mixed layer of the Southern Ocean is typically lower than 0.2 nmol/L (Tagliabue et al., 2012), which is much lower than the requirement of AOA. Studies of the surface layer in the Indian Ocean sector of the Southern Ocean have shown that iron is the main factor constraining Vmax in winter (Mdutyana et al., 2022b). In the waters off the Kerguelen Plateau (marked in Fig. 1), bathymetry-induced CDW increased the iron supply, resulting in an NR of up to

The continental shelf is another main source of DFe- and Fe-binding ligands in the Southern Ocean (Herraiz-Borreguero et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2021, 2022), therefore the intrusion of CDW onto the shelf and the offshore transport of Fe-rich shelf waters potentially benefit nitrification. This shelf effect may be reflected at shelf Site P1-11 (bottom depth 505 m, nitrate anomaly 1.1), where the NRin situ at the depth of 50−470 m increased significantly [20.1−60.6 nmol/(L·d), in terms of N], the mean NRdark at the depth of 25−300 m was as high as (81.8 ± 9.2) nmol/(L·d) (in terms of N), indicating that sufficient Fe promoted the recovery of NRdark. The slope Site P1-09 had a higher [

Upwelling-induced iron may alleviate photoinhibition and enhance the NR in the upper water. This was well represented by the difference in NR response to substrate enrichment (Fig. 4b). At Site C9-05, strongly affected by CDW upwelling (nitrate anomaly 3.91), NR at 60 m responded much faster to substrate supply than at Site C9-09 (nitrate anomaly 2.21, and negative values at surrounding sites, Fig. 9a) at 25 m. In the field, both NRin situ and NRdark responded to upwelling and substrate enhancement, their responses may have differed slightly. The alleviation of light inhibition in NRin situ likely depends mainly on the

Upwelling sites:

Non-upwelling sites:

Comparing the two fitting equations, the photoinhibition at the upwelling site decays faster with depth, whereas the photoinhibition at the non-upwelling site is stronger. The profiles of the mean NR values at the upwelling and non-upwelling sites are shown in Fig. 10. The peak values of NRin situ and NRdark at 100 m at the upwelling sites were 3.1 times and 2.9 times higher than those at non-upwelling sites, respectively. NR values in upwelling sites at 75 m were comparable to those at 100 m, in contrast to non-upwelling sites, where NR values at 75 m were reduced by 1.9 times compared to those at 100 m. The difference in the percentage of photoinhibition at each depth between the upwelling and non-upwelling sites reflected the degree of photoinhibition alleviation caused by the CDW upwelling. A simple estimate showed that the alleviation to light inhibition varied from 2.2% ± 2.5% to 45.4% ± 5.3%, with the highest at 75 m (45.4% ± 5.3%), followed by 100 m (36.4% ± 2.6%) (Fig. 10). Therefore, CDW upwelling alleviated photoinhibition in the euphotic zone, thereby improving NR.

Light inhibition is the primary limiting factor for nitrification in the Southern Ocean during summer. However, we reveal a mechanism for alleviating photoinhibition on nitrification. First,

Our study breaks the previous notion that summer epipelagic nitrification in the Southern Ocean is unimportant due to photoinhibition. The euphotic zone in the Southern Ocean is a feeding hotspot for zooplankton and has been identified as a significant source of DON,

|

Alcamán-Arias M E, Cifuentes-Anticevic J, Díez B, et al. 2022. Surface ammonia-oxidizer abundance during the late summer in the west Antarctic coastal system. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13: 821902, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.821902

|

|

Alonso-Sáez L, Andersson A, Heinrich F, et al. 2011. High archaeal diversity in Antarctic circumpolar deep waters. EnvironmentalMicrobiology Reports, 3(6): 689–697, doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00282.x

|

|

Arp D J, Sayavedra-Soto L A, Hommes N G. 2002. Molecular biology and biochemistry of ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas europaea. Archives of Microbiology, 178(4): 250–255, doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0452-0

|

|

Baer S E, Connelly T L, Sipler R E, et al. 2014. Effect of temperature on rates of ammonium uptake and nitrification in the western coastal Arctic during winter, spring, and summer. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 28(12): 1455–1466, doi: 10.1002/2013gb004765

|

|

Beman J M, Popp B N, Alford S E. 2012. Quantification of ammonia oxidation rates and ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria at high resolution in the Gulf of California and eastern tropical North Pacific Ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 57(3): 711–726, doi: 10.4319/lo.2012.57.3.0711

|

|

Bianchi M, Feliatra F, Tréguer P, et al. 1997. Nitrification rates, ammonium and nitrate distribution in upper layers of the water column and in sediments of the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 44(5): 1017–1032, doi: 10.1016/s0967-0645(96)00109-9

|

|

Cavagna A J, Fripiat F, Elskens M, et al. 2015. Production regime and associated N cycling in the vicinity of Kerguelen Island, Southern Ocean. Biogeosciences, 12(21): 6515–6528, doi: 10.5194/bg-12-6515-2015

|

|

Cavan E L, Belcher A, Atkinson A, et al. 2019. The importance of Antarctic krill in biogeochemical cycles. Nature Communications, 10(1): 4742, doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12668-7

|

|

Chen Yangjun, Chen Jinxu, Wang Yi, et al. 2023. Sources and transformations of nitrite in the Amundsen Sea in summer 2019 and 2020 as revealed by nitrogen and oxygen isotopes. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 42(4): 16–24, doi: 10.1007/s13131-022-2111-4

|

|

Clark D R, Rees A P, Ferrera C M, et al. 2022. Nitrite regeneration in the oligotrophic Atlantic Ocean. Biogeosciences, 19(5): 1355–1376, doi: 10.5194/bg-19-1355-2022

|

|

Clark D R, Widdicombe C E, Rees A P, et al. 2016. The significance of nitrogen regeneration for new production within a filament of the Mauritanian upwelling system. Biogeosciences, 13(10): 2873–2888, doi: 10.5194/bg-13-2873-2016

|

|

Damashek J, Pettie K P, Brown Z W, et al. 2017. Regional patterns in ammonia-oxidizing communities throughout Chukchi Sea waters from the Bering Strait to the Beaufort Sea. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 79(3): 273–286, doi: 10.3354/ame01834

|

|

Davidson A T, Scott F J, Nash G V, et al. 2010. Physical and biological control of protistan community composition, distribution and abundance in the seasonal ice zone of the Southern Ocean between 30°E and 80°E. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 57(9–10): 828–848, doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.02.011

|

|

DeVries T. 2014. The oceanic anthropogenic CO2 sink: storage, air-sea fluxes, and transports over the industrial era. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 28(7): 631–647, doi: 10.1002/2013gb004739

|

|

Feng Yubin, Li Dong, Zhao Jun, et al. 2022. Effects of sea ice melt water input on phytoplankton biomass and community structure in the eastern Amundsen Sea. Advances in Polar Science, 33(1): 14–27, doi: 10.13679/j.advps.2021.0017

|

|

Fernández C, Farías L. 2012. Assimilation and regeneration of inorganic nitrogen in a coastal upwelling system: ammonium and nitrate utilization. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 451: 1–14, doi: 10.3354/meps09683

|

|

Fernández C, Farías L, Alcaman M E. 2009. Primary production and nitrogen regeneration processes in surface waters of the Peruvian upwelling system. Progress in Oceanography, 83(1–4): 159–168, doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2009.07.010

|

|

Francis C A, Roberts K J, Beman J M, et al. 2005. Ubiquity and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in water columns and sediments of the ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(41): 14683–14688, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506625102

|

|

Fripiat F, Elskens M, Trull T W, et al. 2015. Significant mixed layer nitrification in a natural iron-fertilized bloom of the Southern Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 29(11): 1929–1943, doi: 10.1002/2014gb005051

|

|

Fukushima T, Wu Y J, Whang L M. 2012. The influence of salinity and ammonium levels on amoA mRNA expression of ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes. Water Science and Technology, 65(12): 2228–2235, doi: 10.2166/wst.2012.142

|

|

Füssel J, Lam P, Lavik G, et al. 2012. Nitrite oxidation in the Namibian oxygen minimum zone. The ISME Journal, 6(6): 1200–1209, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.178

|

|

Gao Libao, Zu Yongcan, Guo Guijun, et al. 2022. Recent changes and distribution of the newly-formed Cape Darnley bottom water, East Antarctica. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 201: 105119, doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2022.105119

|

|

Glibert P M, Wilkerson F P, Dugdale R C, et al. 2016. Pluses and minuses of ammonium and nitrate uptake and assimilation by phytoplankton and implications for productivity and community composition, with emphasis on nitrogen-enriched conditions. Limnology and Oceanography, 61(1): 165–197, doi: 10.1002/lno.10203

|

|

Gruber N, Bakker D C E, DeVries T, et al. 2023. Trends and variability in the ocean carbon sink. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 4(2): 119–134, doi: 10.1038/s43017-022-00381-x

|

|

Guerrero M A, Jones R D. 1996. Photoinhibition of marine nitrifying bacteria. Ⅰ. wavelength-dependent response. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 141: 183–192, doi: 10.3354/meps141183

|

|

Gwak J H, Awala S I, Kim S J, et al. 2023. Transcriptomic insights into archaeal nitrification in the Amundsen Sea Polynya, Antarctica. Journal of Microbiology, 61(11): 967–980, doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2763233/v1

|

|

Healey F P. 1980. Slope of the Monod equation as an indicator of advantage in nutrient competition. Microbial Ecology, 5(4): 281–286, doi: 10.1007/bf02020335

|

|

Herraiz-Borreguero L, Lannuzel D, van der Merwe P, et al. 2016. Large flux of iron from the Amery Ice Shelf marine ice to Prydz Bay, East Antarctica. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121(8): 6009–6020, doi: 10.1002/2016jc011687

|

|

Heywood K J, Sparrow M D, Brown J, et al. 1999. Frontal structure and Antarctic bottom water flow through the Princess Elizabeth Trough, Antarctica. Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅰ: Oceanographic Research Papers, 46(7): 1181–1200, doi: 10.1016/s0967-0637(98)00108-3

|

|

Hollibaugh J T. 2017. Oxygen and the activity and distribution of marine Thaumarchaeota. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 9(3): 186–188, doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12534

|

|

Hooper A B, Terry K R. 1974. Photoinactivation of ammonia oxidation in Nitrosomonas. Journal of Bacteriology, 119(3): 899–906, doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.899-906.1974

|

|

Horak R E A, Qin Wei, Bertagnolli A D, et al. 2018. Relative impacts of light, temperature, and reactive oxygen on thaumarchaeal ammonia oxidation in the North Pacific Ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 63(2): 741–757, doi: 10.1002/lno.10665

|

|

Horak R E A, Qin Wei, Schauer A J, et al. 2013. Ammonia oxidation kinetics and temperature sensitivity of a natural marine community dominated by Archaea. The ISME Journal, 7(10): 2023–2033, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.75

|

|

Hubot N D, Giering S L C, Füssel J, et al. 2021. Evidence of nitrification associated with globally distributed pelagic jellyfish. Limnology and Oceanography, 66(6): 2159–2173, doi: 10.1002/lno.11736

|

|

Kalanetra K M, Bano N, Hollibaugh J T. 2009. Ammonia-oxidizing Archaea in the Arctic Ocean and Antarctic coastal waters. Environmental Microbiology, 11(9): 2434–2445, doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01974.x

|

|

Kemeny P C, Weigand M A, Zhang Run, et al. 2016. Enzyme-level interconversion of nitrate and nitrite in the fall mixed layer of the Antarctic Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 30(7): 1069–1085, doi: 10.1002/2015gb005350

|

|

Kim J G, Park S J, Quan Zhexue, et al. 2014. Unveiling abundance and distribution of planktonic Bacteria and Archaea in a polynya in Amundsen Sea, Antarctica. Environmental Microbiology, 16(6): 1566–1578, doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12287

|

|

Kim J G, Park S J, Sinninghe Damsté J S, et al. 2016. Hydrogen peroxide detoxification is a key mechanism for growth of ammonia-oxidizing archaea. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(28): 7888–7893, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605501113

|

|

Law C S, Ling R D. 2001. Nitrous oxide flux and response to increased iron availability in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 48(11–12): 2509–2527, doi: 10.1016/s0967-0645(01)00006-6

|

|

Liu Li, Chen Mingming, Wan Xianhui, et al. 2023. Reduced nitrite accumulation at the primary nitrite maximum in the cyclonic eddies in the western North Pacific subtropical gyre. Science Advances, 9(33): eade2078, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ade2078

|

|

Liu Hao, Zhou Peng, Cheung Shunyan, et al. 2022. Distribution and oxidation rates of Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea influenced by the coastal upwelling off eastern Hainan Island. Microorganisms, 10(5): 952, doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10050952

|

|

Lomas M W, Glibert P M. 2000. Comparisons of nitrate uptake, storage, and reduction in marine diatoms and flagellates. Journal of Phycology, 36(5): 903–913, doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2000.99029.x

|

|

Lu Shimin, Liu Xingguo, Liu Chong, et al. 2020. Influence of photoinhibition on nitrification by ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in aquatic ecosystems. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 19(3): 531–542, doi: 10.1007/s11157-020-09540-2

|

|

Lücker S, Wagner M, Maixner F, et al. 2010. A Nitrospira metagenome illuminates the physiology and evolution of globally important nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(30): 13479–13484, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003860107

|

|

Luo Haiwei, Tolar B B, Swan B K, et al. 2014. Single-cell genomics shedding light on marine Thaumarchaeota diversification. The ISME Journal, 8(3): 732–736, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.202

|

|

MacIsaac J J, Dugdale R C. 1969. The kinetics of nitrate and ammonia uptake by natural populations of marine phytoplankton. Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts, 16(1): 45–57, doi: 10.1016/0011-7471(69)90049-7

|

|

Martens-Habbena W, Berube P M, Urakawa H, et al. 2009. Ammonia oxidation kinetics determine niche separation of nitrifying Archaea and Bacteria. Nature, 461(7266): 976–979, doi: 10.1038/nature08465

|

|

Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai Panmao, Pirani A, et al. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi: 10.1017/9781009157896

|

|

Mdutyana M, Marshall T, Sun Xin, et al. 2022a. Controls on nitrite oxidation in the upper Southern Ocean: insights from winter kinetics experiments in the Indian sector. Biogeosciences, 19(14): 3425–3444, doi: 10.5194/bg-19-3425-2022

|

|

Mdutyana M, Sun Xin, Burger J M, et al. 2022b. The kinetics of ammonium uptake and oxidation across the Southern Ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 67(4): 973–991, doi: 10.1002/lno.12050

|

|

Mdutyana M, Thomalla S J, Philibert R, et al. 2020. The seasonal cycle of nitrogen uptake and nitrification in the Atlantic Sector of the Southern Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 34(7): e2019GB006363, doi: 10.1029/2019GB006363

|

|

Merbt S N, Stahl D A, Casamayor E O, et al. 2012. Differential photoinhibition of bacterial and archaeal ammonia oxidation. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 327(1): 41–46, doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02457.x

|

|

Morris J J, Rose A L, Lu Zhiying. 2022. Reactive oxygen species in the world ocean and their impacts on marine ecosystems. Redox Biology, 52: 102285, doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102285

|

|

Murray A E, Wu Keying, Moyer C L, et al. 1999. Evidence for circumpolar distribution of planktonic Archaea in the Southern Ocean. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 18(3): 263–273, doi: 10.3354/ame018263

|

|

Newell S E, Fawcett S E, Ward B B. 2013. Depth distribution of ammonia oxidation rates and ammonia-oxidizer community composition in the Sargasso Sea. Limnology and Oceanography, 58(4): 1491–1500, doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.4.1491

|

|

Olson R J. 1981. 15N tracer studies of the primary nitrite maximum. Journal of Marine Research, 39(2): 203–226

|

|

Orsi A H, Whitworth T, Nowlin W D. 1995. On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅰ: Oceanographic Research Papers, 42(5): 641–673, doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(95)00021-w

|

|

Painter S C. 2011. On the significance of nitrification within the euphotic zone of the subpolar North Atlantic (Iceland basin) during summer 2007. Journal of Marine Systems, 88(2): 332–335, doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2011.05.001

|

|

Peng Xuefeng, Fawcett S E, van Oostende N, et al. 2018. Nitrogen uptake and nitrification in the subarctic North Atlantic Ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 63(4): 1462–1487, doi: 10.1002/lno.10784

|

|

Peng Xuefeng, Fuchsman C A, Jayakumar A, et al. 2016. Revisiting nitrification in the Eastern Tropical South Pacific: a focus on controls. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121(3): 1667–1684, doi: 10.1002/2015jc011455

|

|

Petrou K, Kranz S A, Trimborn S, et al. 2016. Southern Ocean phytoplankton physiology in a changing climate. Journal of Plant Physiology, 203: 135–150, doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.05.004

|

|

Proctor C, Coupel P, Casciotti K, et al. 2023. Light, ammonium, pH, and phytoplankton competition as environmental factors controlling nitrification. Limnology and Oceanography, 68(7): 1490–1503, doi: 10.1002/lno.12359

|

|

Qin Wei, Amin S A, Martens-Habbena W, et al. 2014. Marine ammonia-oxidizing archaeal isolates display obligate mixotrophy and wide ecotypic variation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(34): 12504–12509, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324115111

|

|

Raes E J, Bodrossy L, van de Kamp J, et al. 2018. Oceanographic boundaries constrain microbial diversity gradients in the South Pacific Ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(35): EB266–EB275, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719335115

|

|

Raes E J, van de Kamp J, Bodrossy L, et al. 2020. N2 fixation and new insights into nitrification from the ice-edge to the equator in the South Pacific Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7: 389, doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00389

|

|

Rees A P, Woodward E M S, Joint I. 2006. Concentrations and uptake of nitrate and ammonium in the Atlantic Ocean between 60°N and 50°S. Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 53(14–16): 1649–1665, doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2006.05.008

|

|

Santoro A E, Buchwald C, Knapp A N, et al. 2021. Nitrification and Nitrous Oxide production in the offshore waters of the Eastern Tropical South Pacific. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 35(2): e2020GB006716, doi: 10.1029/2020gb006716

|

|

Santoro A E, Dupont C L, Richter R A, et al. 2015. Genomic and proteomic characterization of “Candidatus Nitrosopelagicus brevis”: an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from the open ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(4): 1173–1178, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416223112

|

|

Santoro A E, Richter R A, Dupont C L. 2019. Planktonic marine archaea. Annual Review of Marine Science, 11: 131–158, doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-121916-063141

|

|

Santoro A E, Saito M A, Goepfert T J, et al. 2017. Thaumarchaeal ecotype distributions across the equatorial Pacific Ocean and their potential roles in nitrification and sinking flux attenuation. Limnology and Oceanography, 62(5): 1984–2003, doi: 10.1002/lno.10547

|

|

Sarthou G, Bucciarelli E, Chever F, et al. 2011. Labile Fe(Ⅱ) concentrations in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean along a transect from the subtropical domain to the Weddell Sea Gyre. Biogeosciences, 8(9): 2461–2479, doi: 10.5194/bg-8-2461-2011

|

|

Shafiee R T, Snow J T, Zhang Qiong, et al. 2019. Iron requirements and uptake strategies of the globally abundant marine ammonia-oxidising archaeon, Nitrosopumilus maritimus SCM1. The ISME Journal, 13(9): 2295–2305, doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0434-8

|

|

Shiozaki T, Ijichi M, Fujiwara A, et al. 2019. Factors regulating nitrification in the Arctic Ocean: potential impact of sea ice reduction and ocean acidification. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 33(8): 1085–1099, doi: 10.1029/2018gb006068

|

|

Shiozaki T, Ijichi M, Isobe K, et al. 2016. Nitrification and its influence on biogeochemical cycles from the equatorial Pacific to the Arctic Ocean. The ISME Journal, 10(9): 2184–2197, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.18

|

|

Sigman D M, Casciotti K L, Andreani M, et al. 2001. A bacterial method for the nitrogen isotopic analysis of nitrate in seawater and freshwater. Analytical Chemistry, 73(17): 4145–4153, doi: 10.1021/ac010088e

|

|

Sintes E, De Corte D, Haberleitner E, et al. 2016. Geographic distribution of Archaeal Ammonia Oxidizing ecotypes in the Atlantic Ocean. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7: 77, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00077

|

|

Smith J M, Casciotti K L, Chavez F P, et al. 2014a. Differential contributions of archaeal ammonia oxidizer ecotypes to nitrification in coastal surface waters. The ISME Journal, 8(8): 1704–1714, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.11

|

|

Smith J M, Chavez F P, Francis C A. 2014b. Ammonium uptake by phytoplankton regulates nitrification in the sunlit ocean. PLoS One, 9(9): e108173, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108173

|

|

Smith J M, Damashek J, Chavez F P, et al. 2016. Factors influencing nitrification rates and the abundance and transcriptional activity of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in the dark northeast Pacific Ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 61(2): 596–609, doi: 10.1002/lno.10235

|

|

Smith A J R, Nelson T, Ratnarajah L, et al. 2022. Identifying potential sources of iron-binding ligands in coastal Antarctic environments and the wider Southern Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9: 948772, doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.948772

|

|

Smith A J R, Ratnarajah L, Holmes T M, et al. 2021. Circumpolar deep water and shelf sediments support late summer microbial iron remineralization. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 35(11): e2020GB006921, doi: 10.1029/2020gb006921

|

|

Sow S L S, Brown M V, Clarke L J, et al. 2022. Biogeography of Southern Ocean prokaryotes: a comparison of the Indian and Pacific sectors. Environmental Microbiology, 24(5): 2449–2466, doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15906

|

|

Tagliabue A, Mtshali T, Aumont O, et al. 2012. A global compilation of dissolved iron measurements: focus on distributions and processes in the Southern Ocean. Biogeosciences, 9(6): 2333–2349, doi: 10.5194/bg-9-2333-2012

|

|

Talley L D, Pickard G L, EmeryW J, et al. 2011. Descriptive Physical Oceanography. Pittsburgh: Academic Press

|

|

Tolar B B, Powers L C, Miller W L, et al. 2016a. Ammonia oxidation in the ocean can be inhibited by nanomolar concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. Frontiers in Marine Science, 3: 237, doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00237

|

|

Tolar B B, Reji L, Smith J M, et al. 2020. Time series assessment of Thaumarchaeota ecotypes in Monterey Bay reveals the importance of water column position in predicting distribution-environment relationships. Limnology and Oceanography, 65(9): 2041–2055, doi: 10.1002/lno.11436

|

|

Tolar B B, Ross M J, Wallsgrove N J, et al. 2016b. Contribution of ammonia oxidation to chemoautotrophy in Antarctic coastal waters. The ISME Journal, 10(11): 2605–2619, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.61

|

|

Valdés V, Fernandez C, Molina V, et al. 2018. Nitrogen excretion by copepods and its effect on ammonia-oxidizing communities from a coastal upwelling zone. Limnology and Oceanography, 63(1): 278–294, doi: 10.1002/lno.10629

|

|

Vichi M, Pinardi N, Masina S. 2007. A generalized model of pelagic biogeochemistry. for the global ocean ecosystem. Part Ⅰ: theory. Journal of Marine Systems, 64(1–4): 89–109, doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2006.03.006

|

|

Wan Xianhui, Sheng Huaxia, Dai Minhan, et al. 2018. Ambient nitrate switches the ammonium consumption pathway in the euphotic ocean. Nature Communications, 9(1): 915, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03363-0

|

|

Wan Xianhui, Sheng Huaxia, Dai Minhan, et al. 2023. Epipelagic nitrous oxide production offsets carbon sequestration by the biological pump. Nature Geoscience, 16(1): 29–36, doi: 10.1038/s41561-022-01090-2

|

|

Ward B B. 2011a. Nitrification in the ocean. In: Ward B B, Daniel J A, Martin G K, eds. Nitrification. Washington: Academic Press, 323–345, doi: 10.1128/9781555817145.ch13

|

|

Ward B B. 2011b. Chapter thirteen—measurement and distribution of nitrification rates in the oceans. Methods in Enzymology, 486: 307–323, doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-381294-0.00013-4

|

|

Williams G D, Nicol S, Aoki S, et al. 2010. Surface oceanography of BROKE-West, along the Antarctic margin of the south-west Indian Ocean (30°E–80°E). Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 57(9–10): 738–757, doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.04.020

|

|

Xu Min Nina, Li Xiaolin, Shi Dalin, et al. 2019. Coupled effect of substrate and light on assimilation and oxidation of regenerated nitrogen in the euphotic ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 64(3): 1270–1283, doi: 10.1002/lno.11114

|

|

Yool A, Martin A P, Fernández C, et al. 2007. The significance of nitrification for oceanic new production. Nature, 447(7147): 999–1002, doi: 10.1038/nature05885

|

|

Zakem E J, Al-Haj A, Church M J, et al. 2018. Ecological control of nitrite in the upper ocean. Nature Communications, 9(1): 1206, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03553-w

|

|

Zakem E J, Bayer B, Qin Wei, et al. 2022. Controls on the relative abundances and rates of nitrifying microorganisms in the ocean. Biogeosciences, 19(23): 5401–5418, doi: 10.5194/bg-19-5401-2022

|

|

Zhang Yao, Qin Wei, Hou Lei, et al. 2020. Nitrifier adaptation to low energy flux controls inventory of reduced nitrogen in the dark ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(9): 4823–4830, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912367117

|

|

Zu Yongcan, Gao Libao, Guo Guijun, et al. 2022. Changes of circumpolar deep water between 2006 and 2020 in the south-west Indian Ocean, East Antarctica. Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 197: 105043, doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2022.105043

|