| Citation: | Zhangliang Wei, Yating Zhang, Fangfang Yang, Lijuan Long. Increased light availability enhances tolerance against ocean acidification-related stress in the calcifying macroalga Halimeda opuntia[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2022, 41(12): 123-132. doi: 10.1007/s13131-022-2037-x |

The atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration has been rising rapidly over the past 250 years owing to the large-scale use of fossil fuels and deforestation, and it is predicted to exceed 1 000 ppmv by the end of 2100 if anthropogenic CO2 emissions are not effectively managed (Fabry et al., 2008; IPCC, 2013). Friedlingstein et al. (2019) estimated that the oceans have already absorbed CO2 nearly (2.5±0.6) Gt/a from 2009 to 2018. This has resulted in a ~0.1 unit decrease in pH at the oceans’ surface layers and is projected to reach a mean of pH 7.8 by the end of this century (IPCC, 2013). This CO2-induced ocean acidification (OA) has received much attention and may cause large-scale changes in many marine ecosystems owing to the increased bicarbonate (

The aragonite-depositing green algal genus Halimeda (Bryopsidales) is found widely in the tropical sea area (Wei et al., 2020b). This algal genus is composed of calcified green segments that play a major role as carbonate sediment producers (Payri, 1988; Sinutok et al., 2012; Wizemann et al., 2015). Halimeda species produce CaCO3 an estimated 0.15–0.40 Gt/(m2·a), which accounts for approximately 8.0% of the total calcium produced by coral reef ecosystems (Milliman, 1993; Hillis, 1997). Thus, Halimeda species are considered a carbon sink for the long-term storage of atmospheric CO2 emissions (Kinsey and Hopley, 1991; Rees et al., 2007). Peach et al. (2017) noted that photosynthesis, calcification rates (Gnet), and aragonite crystal formation varied among six Halimeda species, but they were not obviously affected under elevated pCO2 (1 300 ppmv) conditions. However, Wei et al. (2020a) found that elevated pCO2 (1 600 ppmv) has an adverse influence on growth, Gnet values, maximum quantum yields of photosystem II (Fv/Fm), and chlorophyll a (Chl a) accumulations in Halimeda cylindracea and Halimeda lacunalis. Although species-level variations in response to OA have been documented in Gnet values and photosynthetic performance in field and laboratory experiments, significant gaps still exist in our knowledge of the metabolic responses to OA by these calcifiers owing to the pCO2 concentrations used (e.g., 1 300 ppmv vs. 1 600 ppmv) and other potentially confounding factors, such as nutrient availability (Hofmann et al., 2014), seawater flow (Comeau et al., 2014a), temperature (Campbell et al., 2016), and irradiance (Zou and Gao, 2010; Vásquez-Elizondo and Enríquez, 2017; Wei et al., 2020a).

In the open ocean, light is another vital environmental factor for the growth and distribution of Halimeda species (Peach et al., 2017). Variations in light availability can affect algal photosynthesis, carbohydrate synthesis, and substance accumulation through the photo-energy absorbed by light-harvesting complexes (Porzio et al., 2011; Celis-Plá et al., 2017). Moderate increases in light intensity have positive influences on the physiological performance of fleshy and calcifying macroalgae (Teichberg et al., 2013; Bao et al., 2019). Teichberg et al. (2013) found that owing to differences in the incidence of underwater light, the growth, photosynthetic performance, and tissue composition (total organic carbon and nitrogen) of Halimeda opuntia at depths of 5 m were significantly greater than those at 15 m in Curacao, Netherlands Antilles. High sunlight levels in relatively shallow marine environments provide sufficient solar energy for calcifying macroalgae to uptake

Elevated ocean pCO2 has been shown to affect physiological processes in Halimeda, such as growth, calcification and skeletal minerology, with the later making them potentially more susceptible to herbivory (Hofmann et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2020a). Therefore, it is essential that these calcifying macroalgae make suitable modifications to address OA-related stress. Functional soluble organic osmolytes, such as proline, soluble carbohydrate (SC), soluble protein (SP), and free amino acids (FAAs), are secreted in abundance and protect the integrity of cellular structures, as well as other defense-related enzymes systems (Chen et al., 2017, 2018; Wei et al., 2020a). However, it is still not known whether these marine calcifying autotrophs will be able to tolerate future OA conditions, because the adverse effects of continued OA drive these calcifying species closer to their physiological tolerance limits (O’Donnell et al., 2010; Koch et al., 2013). Furthermore, some studies have indicated that a moderate increase in light availability may enhance the metabolic activities of Halimeda species in response to OA, indicating its potential role in mitigating adverse effects on these carbonate producers (Teichberg et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2020a).

The South China Sea is one of the most multifarious coral community habitats (Morton and Blackmore, 2001). The species of H. opuntia can be found widely distributed in coral reefs and lagoons, and it is most abundant at shallow depths (Wei et al., 2019, 2020b). At specific growth locations and over depth ranges, H. opuntia experiences varied sunlight irradiance conditions during the daytime (El-Manawy and Shafik, 2008; Peach et al., 2017). Although elevated light intensities have been shown to positively affect the physiological performance of Halimeda, the combined effects of OA and light intensity are unknown. Thus, to improve our knowledge of anti-stress responses in H. opuntia, a coupling experiment was conducted to examine growth, calcification, photosynthesis performance, soluble cell components, and metabolic enzyme-driven H. opuntia responses to CO2 enrichment under moderately increased light availability. The resulting detailed physiological descriptions of OA provide an important scientific basis for predicting Halimeda spatial distributions in different seawater depths and for population protection during global climate changes.

Samples of H. opuntia were collected by scuba diving in a back reef lagoon in the South China Sea (17.03°–17.07°N, 111.28°–111.32°E) at depths ranging from 12–15 m in July 2019. All the individuals were carefully detached from the sandy substrate. After collection, algal thalli were immediately incubated in aquaria in the ship having flow-through systems receiving ambient seawater and transported back to the marine research laboratory in Sanya, China.

For acclimation, the algae were reared in an aerated mesocosm tank (1 200 L) with a constant supply of fresh sandy-filtered seawater (~30 L/min) in the laboratory for 2 weeks. Ambient seawater conditions consisted of 27.0℃, 32 psu, pH 8.1, and 80 μmol photons/(m2·s) of photosynthetically active radiation with a 12:12 h day/night cycle in accordance with the method reported by Hofmann et al. (2014). After a 2-week acclimation period, thalli of H. opuntia displayed healthy green segments and no mortality was detected, indicating that subsequent experiments could be undertaken.

For the laboratory trial, healthy thalli of H. opuntia were randomly assigned to 2×3 factorial combination of two seawater pCO2 levels and three light intensities (Table S1) to determine the mixed effects on the physiological performance of H. opuntia after 4 weeks (November 10 to December 8, 2019). For each treatment, there were 10 individuals (120–130 g fresh weight (FW) in total) in a 30-L transparent tank, and three biological replications were prepared per treatment. Filtered seawater was changed twice a week. The OA (elevated pCO2) was achieved by bubbling pure CO2 mixed with ambient air automatically into seawater in each tank (CE100C, Wuhan Ruihua Instrument and Equipment Ltd., Wuhan, China). High pCO2 (HC) was set at 1 400 ppmv, which is the level predicted under extreme conditions by the end of this century (Caldeira and Wickett, 2005). The low CO2 concentration (LC) was 400 ppmv, which is the current local average pCO2 level. Light intensities were set at three levels, 30 (low, LL), 150 (middle, ML), and 240 (high, HL) μmol photons/(m2·s), that created using full-spectrum fluorescent aquarium lamps (Giesemann, Nettetal, Germany) and monitored by an optical quantum probe (ELDONET Terrestrial Spectro-radiometer, Frankfurt, Germany). These three light levels were set based on the saturation light (Ik) values of Halimeda species (Beach et al., 2003; Campbell et al., 2016). Although the light intensities selected in the present study were lower than at the sampling site (300–500 μmol photons/(m2·s)), previous research has revealed that Ik values in situ typically range from 30 μmol photons/(m2·s) to 250 μmol photons/(m2·s) (Beach et al., 2003; Hofmann et al., 2014; Campbell et al., 2016), which includes the light intensity ranges selected in the present study.

To ensure the consistency of seawater among treatments, seawater condition monitoring was conducted daily at 10:00 during the 4-week experimental period. Seawater temperature and salinity were monitored daily by a calibrated handle YSI meter (YSI Professional Plus, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). The pH (NBS scale) was determined using an S220 pH electrode (relative accuracy ±0.01 units, Thermo Scientific Orion, USA). Before each measurement, the pH electrode was calibrated using a standard buffer solution (pH 7 and 10). The seawater parameter (25.00 mL) for total alkalinity (TA) sampled from each aquarium was mixed with 8 μL of 50% saturated HgCl2 solution and then temporarily stored in brown glass bottles at 4℃ under dark conditions until used. The TA was determined using potentiometric titrations of three replicate seawater samples and alkalinity reference materials (CRM; Andrew Dickson Lab, Scripps Institute of Oceanography) by the Gran titration method (Metrohm 877 Titrino Plus, Titrando Metrohm Inc., Herisau, Switzerland) (Dickson et al., 2007). All the measurements were conducted at 25.0℃ and completed within 24 h of sampling. The levels of dissolved inorganic carbon components (CO2,

The FWs (g) of H. opuntia were measured at the beginning and the end of the experiment. The relative growth rate (RGR; %/d) was calculated using the following formula,

| $$ {\rm{RGR}}=({\rm{ln}}W_{t1}-{\rm{ln}}W_{t0})/(t1-t0)\times 100\%, $$ | (1) |

where Wt1 and Wt0 represent the fresh weights obtained at times t1 and t0 days, respectively, and t1 and t0 represent the two sampling days.

At the end of the experiment, the instantaneous Gnet was calculated using the TA anomaly technique in accordance with the description by Hofmann et al. (2014). Segments of H. opuntia (1.0 g FW) were sampled and incubated in 0.5-L transparent glass bottles containing filtered seawater under experimental conditions. The samples were constantly mixed with an electro-magnetic stirrer. The calculation of the Gnet (μmol/(g·h)) was based on the following equation in which every mole of formed CaCO3 reduces the TA by two equivalents,

| $$ G_{\rm{net}}=0.5p\times ({\rm{TA}}_0-{\rm{TA}}_{{n}})\times V/({\rm{FW}}\times t), $$ | (2) |

where p represents the density of seawater (1.025 kg/L), TA0 represents the initial TA of seawater, TAn represents the TA of seawater after n hours of incubation (8 h in this study), V is the volume of the incubation chamber (0.5 L in this study), and t represents the incubation time (8 h). The algal FW in this study was 1.0 g.

The photosynthetic performance of H. opuntia was measured at the end of the experiment using pulse amplitude modulated fluorometry by a DIVING-PAM II fluorometer with red light as the modulated light (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). On the sampling date, segments of all the Halimeda thalli in each treatment were selected and adapted in darkness for nearly 20 min before measurements were taken. The Fv/Fm value was obtained using a saturation pulse (5 000 μmol photons /(m2·s), 0.6 s). The relative electron transport (rETR) versus incident irradiance curves (rapid light curves, RLCs), which reflect linear electron transport activity, were determined under different photosynthetically active photon flux levels (approximately 0, 45, 65, 89, 124, 189, 285, 421, 631, unit: μmol photons /(m2·s)) at 1-min intervals. From the RLCs, the maximum relative electron transport rate (rETRmax) was calculated using a nonlinear regression analysis with the following equation described by Eilers and Peeters (1988),

| $$ {{{\rm{rETR}}_{{\rm{max}}}}}=1/[b+2 (ac)^{0.5}], $$ | (3) |

where a, b and c are constant parameters.

The photosynthetic pigments present in segments of H. opuntia from each aquarium (n=3) were determined. A 100.0 mg FW per sample was finely ground in 10 mL of 90% acetone and then stored for 24 h at 4℃ in darkness for extraction. Subsequently, all the extracted solutions from samples were centrifuged at 5 000 r/min for 10 min at 4℃ (Eppendorf centrifuge 5810 R, Hamburg, Germany). Each supernatant was transferred to a quartz cuvette and its absorbance was measured at 664 nm, 647 nm and 470 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV 530 Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Contents of Chl a and carotenoids (Car.) were calculated in accordance with the method reported by Wellburn (1994).

Total tissue organic carbon (TCorg) and total nitrogen (TN) contents were measured after the 4-week experimental period. Whole–thallus samples were cleaned of epiphytes, detritus, and sediment by washing with filtered seawater 3–5 times. To determine TCorg, dry tissue samples were acidified with 1 mol/L HCl until no air bubbles were observed. Subsequently, all the samples were dried at 60℃ until no change in dry mass weight was detectable, and then, they were finely ground to powder using an automatic grinding mill (FSTPRP-24, Jingxin, Shanghai, China). Both TCorg and TN were measured using a CHN Elemental Analyzer (Flash EA300, Thermo Scientific, Milan, Italy).

At the end of the experiment, 200.0 mg H. opuntia segments from each aquarium (n=3) were sampled and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. All the samples were ground in 5.0 mL of 20 mol/L veronal buffer (pH 8.3) for the external carbonic anhydrase activity (eCAA) and nitrate reductase activity (NRA) determinations. The eCAA of H. opuntia was measured using the electrometric technique reported by Haglund et al. (1992), while NRA was measured using the method reported by Corzo and Niell (1991).

Approximately 200.0 mg FW H. opuntia segments were finely ground with a mortar and pestle in 10 mL distilled water. Afterwards, the extract was centrifuged at 5 000 r/min for 10 min (Eppendorf centrifuge 5810R, Hamburg, Germany) and then the supernatant was used to determine SC and SP contents using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer. The SC content was determined using the phenol-sulfuric acid method (Kochert, 1978a). The SP content was measured by Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye and standardized with bovine albumin (Kochert, 1978b).

To determine the FAA contents, 200.0 mg FW algae were sampled and finely ground in 4.5 mL of PBS buffer (pH 7.4). The homogenate was centrifuged at 5 000 r/min for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and preserved at 4.0℃. The FAA content was determined using an algal FAAs ELISA Kit (Mlbio, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

All results in this study are presented as a triplicate mean±standard deviation (SD). Origin 8.0 software was used to create the figures and data analyses were processed using Minitab 16.0 software. All the response variables measured during the experiment were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance with pCO2 and light intensities as the independent factors. Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference was used to identify significant differences between treatments and P values were significant at the 95% confidence level.

During the experimental period (Table S2), the average pH values within the HC (1 400 ppmv) and LC (400 ppmv) CO2-treatments were 7.72 and 8.15, respectively. The mean TA values in LC and HC were (2 336±40) μmol/kg and (2 350±28) μmol/kg, respectively, which were not significantly different (P>0.05). The elevated pCO2 significantly altered the carbon chemistry parameters in seawater (P<0.01). Compared with LC, the average CO2 and

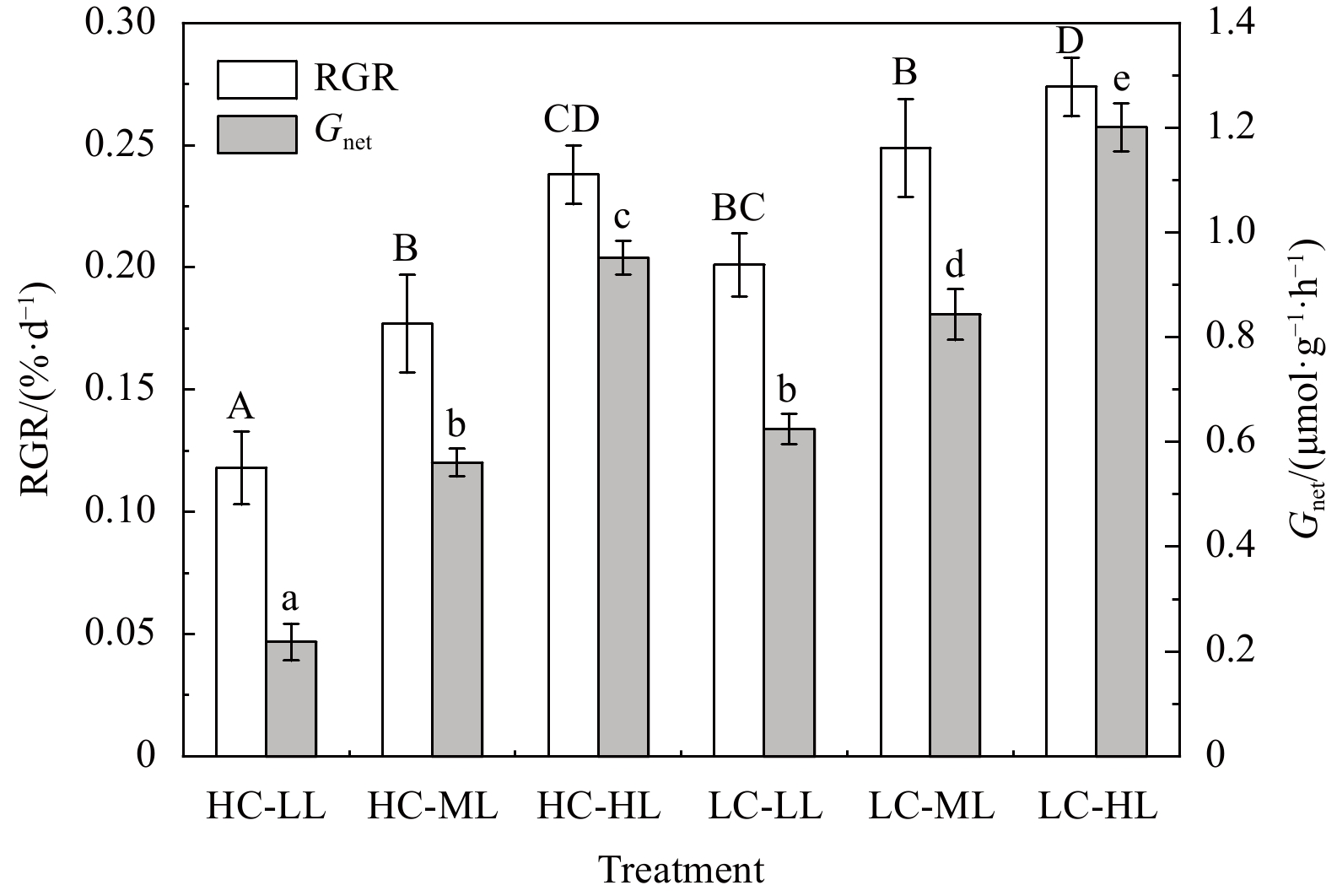

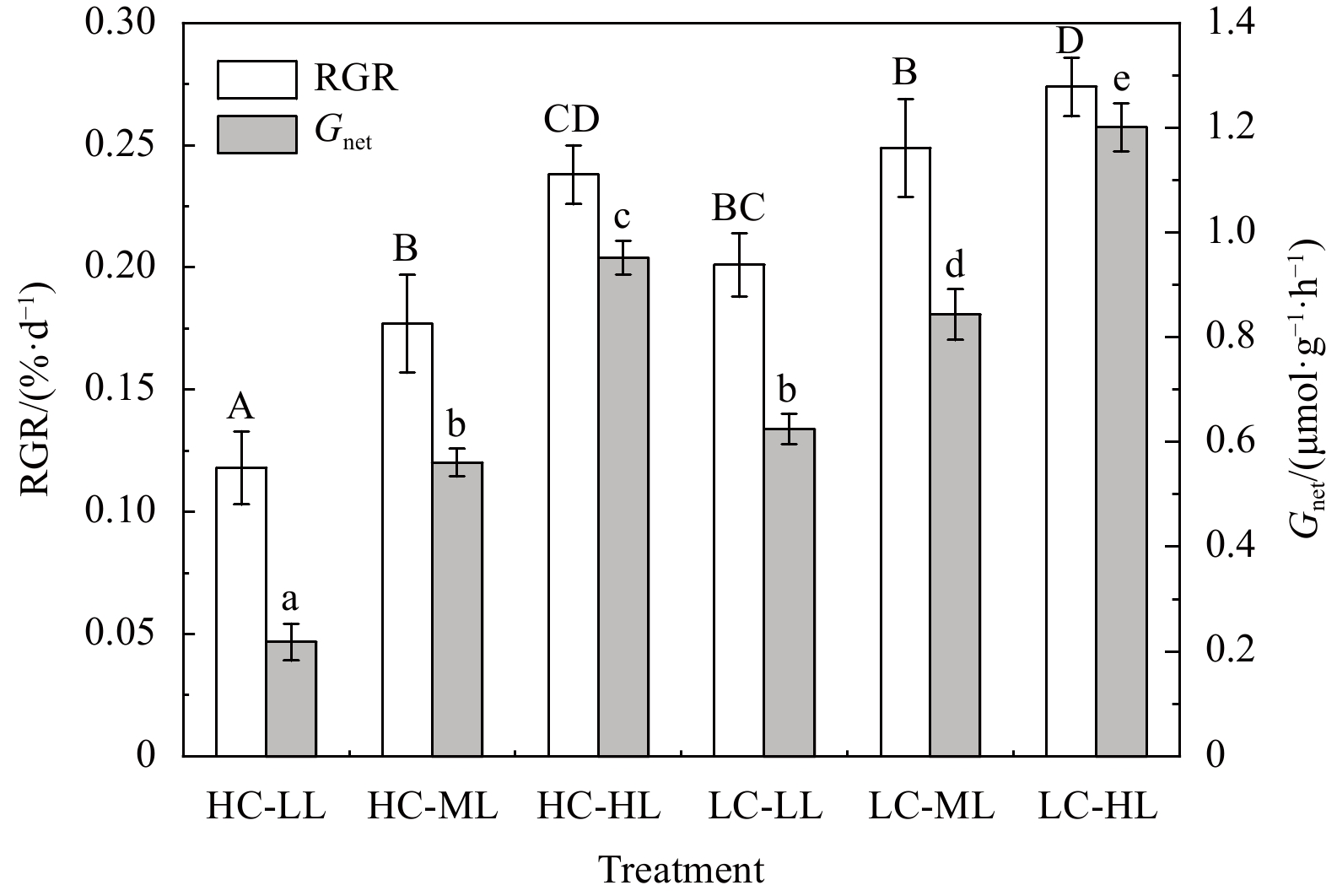

After 4 weeks of exposure, elevated pCO2 and light intensities had significant effects on the RGR and Gnet of H. opuntia (Fig. 1; Table S3). The increased light intensity stimulated growth rates at the two CO2-concentration levels. In contrast to under LL conditions, the RGR increased by 19.28%−33.32% and 26.64%−50.42% under ML and HL conditions, respectively (Fig.1). However, the RGR of H. opuntia under HC conditions significantly declined by 13.14%−41.29% compared with under LC conditions. The Gnet decreased by nearly three-fold under HC-LL conditions ((0.218±0.035) μmol/(g·h)) compared with under LC-LL conditions ((0.625±0.042) μmol/(g·h)). Calcification rates for H. opuntia increased along with light intensity, as shown in Fig. 1, regardless of the pCO2 level.

Rapid light curves indicated there were significant effects of HC on the rETR of H. opuntia under HL conditions, but not under ML or LL conditions (Fig. 2). Notably, H. opuntia displayed a significant correlation between Fv/Fm and Gnet (Fig. 3). The Fv/Fm values ranged from 0.665 to 0.704 and 0.696 to 0.711 after HC and LC treatments, respectively, regardless of the three light levels (Fig. 4a; Table S3). Conversely, the rETRmax was only significantly affected by light availability (P<0.01). The rETRmax was greater in HL (6.262−6.584 μmol e−/(m2·s)) than in ML (5.357−5.694 μmol e−/(m2·s)) and LL (5.157−5.674 μmol e−/(m2·s)) (Fig. 4a).

There was a significant interaction effect on the Chl a content in H. opuntia (Table 3S). Under HC conditions, the highest Chl a content was obtained in HL treatments ((139.1±15.9) μg/g FW), whereas under LC conditions, the highest Chl a content was measured in LL treatments ((168.6±6.6) μg/g FW) (Fig. 4b). The carotenoids (Car.) content was independently affected by HC and light intensities (P<0.01) (Table 3S). In HC treatments, the Car. contents ranged from (26.36±2.1) μg/mg FW to (36.15±3.6) μg/mg FW, which was 17.75%−40.01% higher than in LC treatments (18.65−26.11 μg/mg FW). Compared with under HL and ML conditions, the Car. contents under LL conditions increased by 32.61%−38.45% and 13.87%−41.34% with HC and LC treatments, respectively (Fig. 4b).

Both CO2 enrichment and increasing light availability resulted in tissue TCorg accumulation in H. opuntia over the 4-week experiment (Fig. 5; Table 3S). Under HC conditions, the TCorg content significantly increased by 13.78%−17.91% compared with under LC conditions (Fig. 5). The highest TCorg content [17.64% ±1.02% dry weight (DW)] occurred during the HC-HL treatments, and the lowest content (13.28% ±1.34% DW) occurred during the LC-LL treatment. The TN content exhibited a similar variation pattern, because the elevated pCO2 significantly stimulated nitrogen accumulation (P=0.041) (Table S3). However, light variation had no effect on the TN content in H. opuntia as shown in Table S3 (P=0.168).

The eCAA was significantly higher under HC conditions than under LC conditions (Fig. 6; Table S3). Under the former, the eCAA of H. opuntia was 0.455−0.518 IU/mg FW, increasing by 13.35%−22.31% compared with under the latter. Increased light availability also played a positive role in regulating eCAA (P<0.01) (Table S3). The NRA was affected by significant interactions between HC and the light intensities (Table S3). The NRA increased under HC conditions, producing values of 0.553−0.698 pg/mg FW, compared with values of 0.361−0.526 pg/mg FW under LC conditions (Fig. 6). Moderately increasing the light intensity positively enhanced the NRA levels by 7.78%−26.22% and 30.75%−45.71% under HC and LC conditions, respectively (Fig. 6).

The SC contents measured in H. opuntia at the end of the experiment were notably affected by interactions between HC and the light intensities (P<0.01) (Table S3). Under HC conditions, the SC content ranged from (0.432±0.021) μg/mg FW to (0.668±0.014) μg/mg FW, which was 12.21%−51.47% higher than under LC conditions (0.385−0.441 μg/mg FW). Compared with LL exposure, the SC content under ML to HL exposure (150−240 μmol photons/(m2·s)) increased by 23.38%−54.63% and 12.73%−14.55% under HC and LC conditions, respectively (Fig. 7a). Similar trends were documented for the SP content in H. opuntia. The SP content under HC conditions (0.347−0.547 μg/mg FW) was 11.58%−15.08% higher than under LC conditions (0.311−0.478 μg/mg FW) (Fig. 7b). In addition, there was a positive effect on light availability on SP accumulation, resulting in increases of 25.65%−57.64% and 21.86%−53.70% under HC and LC conditions, respectively (Fig. 7b, Table S3). The SC/SP ratios at HC levels were remarkably greater than at LC levels, and the lowest SC/SP ratio (0.923) occurred during the LC-HL treatment (Fig. 7d). The FAA content in H. opuntia was notably impacted by interactions, as shown in Table S3 (P<0.01), indicating that pCO2 had a strong light level-dependent effects. The HC conditions resulted in a significant increase in the FAA content, which was 33.41%−54.74% higher than in thalli grown under LC conditions. Compared with LL conditions, moderately increasing the light intensity (ML to HL) positively enhanced the FAA contents by 2.19%−11.22% and 12.11%−17.37% under HC and LC conditions, respectively (Fig. 7c).

The effects of CO2-induced OA have caused growing concerns regarding potential stresses on marine calcifying organisms, biological communities, and coral reef ecosystems (Moodley et al., 2000; Feely et al., 2004; Zeebe et al., 2008). As shown in previous studies (Hofmann et al., 2014; Campbell et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2020a), our data suggest that OA has deleterious impacts on growth rates, as well as calcification and photosynthetic processes, in the calcifying macroalga H. opuntia (Figs 1 and 2). However, this study further revealed that photosynthetic performance was positively increased by a higher light availability level, resulting in the accumulation of photosynthetic products (such as SC) and the presence of sufficient energy and carbon skeletons to meet nitrogen requirements (Chen et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2021). Contents of soluble cell components (such as SP and FAA) also increased notably under HC and ML to HL conditions. Moreover, the observed accumulations of TCorg and TN are likely associated with increased metabolic enzyme-driven activities under HC and ML to HL conditions. Thus, moderately increasing the light availability enhanced H. opuntia tolerance to OA. This conclusion is consistent with previous studies reported by Wei et al. (2019, 2020a), in which OA and increased light influenced the photosynthesis and calcification performances of two Halimeda species (H. cylindracea and H. lacunalis) in opposing directions, and the positive effects of moderate increases in light availability offset the adverse effects of the decline in pH caused by elevated pCO2.

Many previous reports on Halimeda species (Teichberg et al., 2013; Hofmann et al., 2014; Campbell et al., 2016; Peach et al., 2017) and other marine calcifiers (Hofmann et al., 2008; Manzello, 2010; O’Donnell et al., 2010) exposed to OA have focused on reduced growth and calcification. In this study, a lower Gnet for H. opuntia was demonstrated under HC conditions compared with LC conditions. Although biological process of growth and calcification drew down TA, the frequent seawater changes (twice a week) intended to counteract such fluctuations in TA, which resulted in TA in LC just a bit lower than in HC. With CO2 enrichment, the pH values and ΩArag drastically decreased (Table S2), which may reduce the formation rate of calcium carbonate in algal tissues (Orr et al., 2005; Andersson et al., 2009; Ries et al., 2009; 2010; Hofmann et al., 2014). A similar conclusion was reported by Comeau et al. (2014b), who demonstrated that the Gnet of Halimeda minima declined by 11.0% when the pCO2 level was double that of ambient conditions, and they suggested that decreased carbonate ion availability inhibits CaCO3 deposition. As observed in other Halimeda species exposed to OA (Vásquez-Elizondo and Enríquez, 2016; Campbell et al., 2016), the calcification data provided evidence that increased light compensated for the potential negative effects of HC conditions through the up-regulation of photosynthesis (Fig. 3). This may be because algal calcification is energetically dependent on photosynthesis and can provide a large fraction of the energy required by the biomineralization process (Chisholm, 2000, 2003; Meyer et al., 2016). Peach et al. (2017) hypothesized that increased photosynthesis compensates for the adverse effects of OA on algal calcification processes. Photosynthesis promotes algal calcification by removing CO2 or bicarbonate from the calcification site, which increases the local pH and, thus, facilitates CaCO3 precipitation (Borowitzka and Larkum, 1976; Campbell et al., 2016).

The HC treatment had adverse effects on thallus photosynthesis in H. opuntia, and the severity of these effects was significant under LL conditions (30 μmol photons/(m2·s)), resulting in declines in Fv/Fm and rETR (Figs 2 and 4a). Similar negative effects of elevated pCO2 on algal photosynthesis have been reported previously in other Halimeda species (Price et al., 2011; Sinutok et al., 2012; Campbell et al., 2016; Meyer et al., 2016). For instance, Price et al. (2011) reported carbonate dissolution and a photosynthetic capacity reduction in H. opuntia after 2 weeks of exposure to pCO2 at (900±90) ppmv, and proposed that this resulted from the depressed expression of CO2 concentrating mechanisms (CCMs). Thus, elevated pCO2 caused a decrease in CCM activity, forcing algal photosynthesis to rely on passive CO2 diffusion, and thereby critically limiting the efficiency of photosynthetic carbon assimilation (Prins et al., 1982; Elzenga and Prins, 1989; Miedema and Prins, 1991; Price et al., 2011). According to the results of present study, the excess dissolved CO2 compromised both photophysiology and ΩArag at the site of calcification in H. opuntia, indicating that OA has adverse effects on this calcifying species. Concurrently, H. opuntia resists OA stress by regulating pigment synthesis. A significant decline in the Chl a content under HC conditions (Fig. 4b) suggested pigment degradation and increased HL-associated stress (Sinutok et al., 2012). However, the Car. contents, especially under LL conditions, accumulated markedly, which supports a natural photoacclimation response of algae to shade adaptation (Boardman, 1977; Teichberg et al., 2013). Based on photosynthetic performance (Fig. 4a), although there was no statistically significant differences between HC-LL and HC-ML, or between HC-ML and HC-HL, a positive correlation between increasing light intensity and Fv/Fm was observed after a 4-week in HC treatments, which indicated that the effects of a moderate increase in light availability could offset the severe impacts of HC-induced low pH (Wei et al., 2020a).

The HC level in seawater modulated TCorg and TN accumulations in algal tissues (Fig. 5), which may result from metabolic enzymatic-driven activities, especially eCAA and NRA (Hofmann et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2021). In the present study, CO2 enrichment, as well as increased light intensities positively enhanced the eCAA of H. opuntia, which contributed to CO2 and

Soluble organic molecules may play roles in buffering metabolic depression to cope with OA-related challenges (Xiong et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017, 2018; Wei et al., 2020a). Light-mediated changes in cellular biochemical composition are associated with the acclimation of algal growth and photosynthesis (Hemm et al., 2004; Zou and Gao, 2013). Under HC conditions, the SC and SP contents were remarkably greater than those of H. opuntia tissues under LC conditions (Fig. 7). Notably, higher light intensities and eCAA may promote photosynthetic processes, which in turn increases photosynthetic product and SC accumulations to improve flexibility and plasticity in response to OA. These modifications may contribute to membrane integrity and ensure the function of cellular activities, and they may provide the physiological basis for resistance to adverse external environments by algal cells (Sun et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2020a). Such shifts in metabolic performance may result from the enhancement of internal and external eCAA levels that facilitate the conversion of CO2 and

In summary, deteriorating marine conditions caused by human activities threaten the diversity levels, distributions and biomasses of coral reef ecosystems, including calcifying macroalgae. The results of the current study indicated that OA has adverse effects on growth, calcification, photosynthesis, and other physiological performances of H. opuntia. However, our results also indicated that increased light availability enhanced anti-stress capabilities through the accumulation of soluble organic molecules, especially SC, SP, and FAA that help alleviate OA stress. Moreover, the up-regulation of eCAA and NRA was significantly promoted by increased CO2 levels and/or light availability, which favored inorganic carbon and nitrogen uptake and assimilation (Losada and Guerrero, 1979; Syrett, 1981). These results increase our understanding of whether marine autotrophic calcifiers have the physiological plasticity (species-specific tolerance) to compensate for the effects of OA and whether they will continue to build carbon skeletons under future CO2 conditions.

Acknowledgements: We thank the staff of Tropical Marine Biological Research Station in Hainan, Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing logistical support. Thanks are also due to editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.|

Andersson A J, Kuffner I B, Mackenzie F T, et al. 2009. Net loss of CaCO3 from coral reef communities due to human induced seawater acidification. Biogeosciences Discussions, 6(1): 2163–2182

|

|

Bao Menglin, Wang Jianhao, Xu Tianpeng, et al. 2019. Rising CO2 levels alter the responses of the red macroalga Pyropia yezoensis under light stress. Aquaculture, 501: 325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.11.011

|

|

Beach K, Walters L, Vroom P, et al. 2003. Variability in the ecophysiology of Halimeda spp. (Chlorophyta, Bryopsidales) on Conch Reef, Florida Keys, USA. Journal of Phycology, 39(4): 633–643. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.02147.x

|

|

Boardman N K. 1977. Comparative photosynthesis of sun and shade plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology, 28: 355–377. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.28.060177.002035

|

|

Borowitzka M A, Larkum A W D. 1976. Calcification in the green alga Halimeda: III. The sources of inorganic carbon for photosynthesis and calcification and a model of the mechanism of calcification. Journal of Experimental Botany, 27(5): 879–893. doi: 10.1093/jxb/27.5.879

|

|

Caldeira K, Wickett M E. 2005. Ocean model predictions of chemistry changes from carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere and ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research, 110(C9): C09S04. doi: 10.1029/2004JC002671

|

|

Campbell J E, Fisch J, Langdon C, et al. 2016. Increased temperature mitigates the effects of ocean acidification in calcified green algae (Halimeda spp. ). Coral Reefs, 35(1): 357–368. doi: 10.1007/s00338-015-1377-9

|

|

Celis-Plá P S M, Martínez B, Korbee N, et al. 2017. Photoprotective responses in a brown macroalgae Cystoseira tamariscifolia to increases in CO2 and temperature. Marine Environmental Research, 130: 157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2017.07.015

|

|

Chen Binbin, Zou Dinghui, Du Hong, et al. 2018. Carbon and nitrogen accumulation in the economic seaweed Gracilaria lemaneiformis affected by ocean acidification and increasing temperature. Aquaculture, 482: 176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2017.09.042

|

|

Chen Binbin, Zou Dinghui, Ma Jiahai. 2016. Interactive effects of elevated CO2 and nitrogen- phosphorus supply on the physiological properties of Pyropia haitanensis (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Journal of Applied Phycology, 28(2): 1235–1243. doi: 10.1007/s10811-015-0628-z

|

|

Chen Binbin, Zou Dinghui, Yang Yufeng. 2017. Increased iron availability resulting from increased CO2 enhances carbon and nitrogen metabolism in the economical marine red macroalga Pyropia haitanensis (Rhodophyta). Chemosphere, 173: 444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.01.073

|

|

Chisholm J R M. 2000. Calcification by crustose coralline algae on the Northern Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Limnology and Oceanography, 45(7): 1476–1484. doi: 10.4319/lo.2000.45.7.1476

|

|

Chisholm J R M. 2003. Primary productivity of reef-building crustose coralline algae. Limnology and Oceanography, 48(4): 1376–1387. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.4.1376

|

|

Comeau S, Edmunds P J, Lantz C A, et al. 2014a. Water flow modulates the response of coral reef communities to ocean acidification. Scientific Reports, 4: 6681

|

|

Comeau S, Edmunds P J, Spindel N B, et al. 2014b. Fast coral reef calcifiers are more sensitive to ocean acidification in short-term laboratory incubations. Limnology and Oceanography, 59(3): 1081–1091. doi: 10.4319/lo.2014.59.3.1081

|

|

Cornwall C E, Hepburn C D, McGraw C M, et al. 2013. Diurnal fluctuations in seawater pH influence the response of a calcifying macroalga to ocean acidification. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1772): 20132201. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2201

|

|

Corzo A, Niell F X. 1991. Determination of nitrate reductase activity in Ulva rigida C. Agardh by the in situ method. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 146(2): 181–191. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(91)90024-Q

|

|

De Beer D, Larkum A W D. 2001. Photosynthesis and calcification in the calcifying algae Halimeda discoidea studied with microsensors. Plant, Cell & Environment, 24(11): 1209–1217

|

|

Dickson A G, Sabine C L, Christian J R. 2007. Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements. Sidney: North Pacific Marine Science Organization, 67–81

|

|

Doney S C, Fabry V J, Feely R A, et al. 2009. Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Annual Review of Marine Science, 1: 169–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163834

|

|

Doo S S, Edmunds P J, Carpenter R C. 2019. Ocean acidification effects on in situ coral reef metabolism. Scientific Reports, 9(1): 12067. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48407-7

|

|

Dupont S, Havenhand J, Thorndyke W, et al. 2008. Near-future level of CO2-driven ocean acidification radically affects larval survival and development in the brittlestar Ophiothrix fragilis. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 373: 285–294. doi: 10.3354/meps07800

|

|

Eilers P H C, Peeters J C H. 1988. A model for the relationship between light intensity and the rate of photosynthesis in phytoplankton. Ecological Modelling, 42(3–4): 199–215

|

|

El-Manawy I M, Shafik M A. 2008. Morphological characterization of Halimeda (Lamouroux) from different biotopes on the Red Sea coral reefs of Egypt. American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, 3(4): 532–538

|

|

Elzenga J T M, Prins H B A. 1989. Light-induced polar pH changes in leaves of Elodea canadensis. I. Effects of carbon concentration and light intensity. Plant Physiology, 91(1): 62–67. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.1.62

|

|

Fabry V J, Seibel B A, Feely R A, et al. 2008. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine fauna and ecosystem processes. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 65(3): 414–432. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsn048

|

|

Feely R A, Sabine C L, Lee K, et al. 2004. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCO3 system in the oceans. Science, 305(5682): 362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1097329

|

|

Fougère F, Le Rudulier D, Streeter J G. 1991. Effects of salt stress on amino acid, organic acid, and carbohydrate composition of roots, bacteroids, and cytosol of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L. ). Plant Physiology, 96(4): 1228–1236. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.4.1228

|

|

Friedlingstein P, Jones M W, O’Sullivan M, et al. 2019. Global carbon budget 2019. Earth System Science Data, 11(4): 1783–1838. doi: 10.5194/essd-11-1783-2019

|

|

Haglund K, Björk M, Ramazanov Z, et al. 1992. Role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis and inorganic-carbon assimilation in the red alga Gracilaria tenuistipitata. Planta, 187(2): 275–281

|

|

Hall-Spencer J M, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Martin S, et al. 2008. Volcanic carbon dioxide vents show ecosystem effects of ocean acidification. Nature, 454(7200): 96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature07051

|

|

Hemm M R, Rider S D, Ogas J, et al. 2004. Light induces phenylpropanoid metabolism in Arabidopsis roots. The Plant Journal, 38(5): 765–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02089.x

|

|

Hillis L. 1997. Coralgal reefs from a calcareous green alga perspective, and a first carbonate budget. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium. Panama: Balboa, 761–766

|

|

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Mumby P J, Hooten A J, et al. 2007. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science, 318(5857): 1737–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.1152509

|

|

Hofmann L C, Heiden J, Bischof K, et al. 2014. Nutrient availability affects the response of the calcifying chlorophyte Halimeda opuntia (L. ) J. V. Lamouroux to low pH. Planta, 239(1): 231–242. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1982-1

|

|

Hofmann G E, O’Donnell M J, Todgham A E. 2008. Using functional genomics to explore the effects of ocean acidification on calcifying marine organisms. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 373: 219–225. doi: 10.3354/meps07775

|

|

IPCC. 2013. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. In: Stocker T F, Qin D H, Plattner G K, et al., eds. Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1535

|

|

Kinsey D W, Hopley D. 1991. The significance of coral reefs as global carbon sinks–response to Greenhouse. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 89(4): 363–377.

|

|

Koch M, Bowes G, Ross C, et al. 2013. Climate change and ocean acidification effects on seagrasses and marine macroalgae. Global Change Biology, 19(1): 103–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02791.x

|

|

Kochert G. 1978a. Carbohydrate determination by phenol sulphuric acid method. In: Hellebust J A, Craigie J S, eds. Handbook of Phycological Methods: Physiological and Biochemical Methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 95–97

|

|

Kochert G. 1978b. Protein determination by dye binding. In: Hellebust J A, Craigie J S, eds. Handbook of Phycological Methods: Physiological and Biochemical Methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 91–93

|

|

Losada M, Guerrero M G. 1979. The photosynthetic reduction of nitrate and its regulation. In: Barber J, ed. Photosynthesis in Relation to Model Systems. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 365–408

|

|

Manzello D P. 2010. Coral growth with thermal stress and ocean acidification: lessons from the eastern tropical Pacific. Coral Reefs, 29(3): 749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0623-4

|

|

Meyer F W, Schubert N, Diele K, et al. 2016. Effect of inorganic and organic carbon enrichments (DIC and DOC) on the photosynthesis and calcification rates of two calcifying green algae from a Caribbean reef lagoon. PLoS ONE, 11(8): e0160268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160268

|

|

Miedema H, Prins H B A. 1991. pH-dependent proton permeability of the plasma membrane is a regulating mechanism of polar transport through the submerged leaves of Potamogeton lucens. Canadian Journal of Botany, 69(5): 1116–1122. doi: 10.1139/b91-143

|

|

Milliman J D. 1993. Production and accumulation of calcium carbonate in the ocean: budget of a nonsteady state. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 7(4): 927–957. doi: 10.1029/93GB02524

|

|

Moodley L, Boschker H T S, Middelburg J J, et al. 2000. Ecological significance of benthic foraminifera: 13C labelling experiments. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 202: 289–295. doi: 10.3354/meps202289

|

|

Morton B, Blackmore G. 2001. South China Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 42(12): 1236–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00240-5

|

|

Moya A, Huisman L, Ball E E, et al. 2012. Whole transcriptome analysis of the coral Acropora millepora reveals complex responses to CO2-driven acidification during the initiation of calcification. Molecular Ecology, 21(10): 2440–2454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05554.x

|

|

O’Donnell M J, Todgham A E, Sewell M A, et al. 2010. Ocean acidification alters skeletogenesis and gene expression in larval sea urchins. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 398: 157–171. doi: 10.3354/meps08346

|

|

Orr J C, Fabry V J, Aumont O, et al. 2005. Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature, 437(7059): 681–686. doi: 10.1038/nature04095

|

|

Payri C E. 1988. Halimeda contribution to organic and inorganic production in a Tahitian reef system. Coral Reefs, 6(3–4): 251–262

|

|

Peach K E, Koch M S, Blackwelder P L, et al. 2017. Calcification and photophysiology responses to elevated pCO2 in six Halimeda species from contrasting irradiance environments on Little Cayman Island reefs. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 486: 114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2016.09.008

|

|

Pierrot D, Lewis E, Wallace D W R. 2006. MS Excel program developed for CO2 system calculations: ORNL/CDIAC-105a. Oak Ridge, Tennessee: Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U. S. Department of Energy

|

|

Porzio L, Buia M C, Hall-Spencer J M. 2011. Effects of ocean acidification on macroalgal communities. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 400(1–2): 278–287

|

|

Price N N, Hamilton S L, Tootell J S, et al. 2011. Species-specific consequences of ocean acidification for the calcareous tropical green algae Halimeda. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 440: 67–78. doi: 10.3354/meps09309

|

|

Prins H B A, Snel J F H, Zanstra P E, et al. 1982. The mechanism of bicarbonate assimilation by the polar leaves of Potamogeton and Elodea. CO2 concentrations at the leaf surface. Plant, Cell & Environment, 5(3): 207–214

|

|

Rees S A, Opdyke B N, Wilson P A, et al. 2007. Significance of Halimeda bioherms to the global carbonate budget based on a geological sediment budget for the Northern Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Coral Reefs, 26: 177–188. doi: 10.1007/s00338-006-0166-x

|

|

Ries J B, Cohen A L, McCorkle D C. 2009. Marine calcifiers exhibit mixed responses to CO2-induced ocean acidification. Geology, 37(12): 1131–1134. doi: 10.1130/G30210A.1

|

|

Ries J B, Cohen A L, McCorkle D C. 2010. A nonlinear calcification response to CO2-induced ocean acidification by the coral Oculina arbuscula. Coral Reefs, 29(3): 661–674. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0632-3

|

|

Rizhsky L, Liang Hongjian, Shuman J, et al. 2004. When defense pathways collide. The response of Arabidopsis to a combination of drought and heat stress. Plant Physiology, 134(4): 1683–1696. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.033431

|

|

Sinutok S, Hill R, Doblin M A, et al. 2012. Microenvironmental changes support evidence of photosynthesis and calcification inhibition in Halimeda under ocean acidification and warming. Coral Reefs, 31(4): 1201–1213. doi: 10.1007/s00338-012-0952-6

|

|

Sun Yanguo, Wang Bo, Jin Shanghui, et al. 2013. Ectopic expression of Arabidopsis glycosyltransferase UGT85A5 enhances salt stress tolerance in tobacco. PLoS ONE, 8(3): e59924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059924

|

|

Sun Changqing, Yang Yanjun, Guo, Zhili, et al. 2015. Effects of fertilization and density on soluble sugar and protein and nitrate reductase of hybrid foxtail millet. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science, 21(5): 1169–1177

|

|

Syrett P J. 1981. Nitrogen metabolism of microalgae. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 210: 182–210

|

|

Teichberg M, Fricke A, Bischof K. 2013. Increased physiological performance of the calcifying green macroalga Halimeda opuntia in response to experimental nutrient enrichment on a Caribbean coral reef. Aquatic Botany, 104: 25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2012.09.010

|

|

Van Oijen T, Van Leeuwe M A, Gieskes W W C, et al. 2004. Effects of iron limitation on photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in the Antarctic diatom Chaetoceros brevis (Bacillariophyceae). European Journal of Phycology, 39(2): 161–171. doi: 10.1080/0967026042000202127

|

|

Vásquez-Elizondo R M, Enríquez S. 2016. Coralline algal physiology is more adversely affected by elevated temperature than reduced pH. Scientific Reports, 6: 19030. doi: 10.1038/srep19030

|

|

Vásquez-Elizondo R M, Enríquez S. 2017. Light absorption in coralline algae (Rhodophyta): a morphological and functional approach to understanding species distribution in a coral reef lagoon. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4: 297. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00297

|

|

Verma D P S. 1999. Osmotic stress tolerance in plants: role of praline and sulfur metabolisms. In: Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, eds. Molecular Responses to Cold, Drought, Heat, and Salt Stress in Higher Plants. Austin: R. G. Landes Company, 153–168

|

|

Vidal-Dupiol J, Zoccola D, Tambutté E, et al. 2013. Genes related to ion-transport and energy production are upregulated in response to CO2-driven pH decrease in corals: new insights from transcriptome analysis. PLoS ONE, 8(3): e58652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058652

|

|

Wei Zhangliang, Long Chao, Yang Fangfang, et al. 2020a. Increased irradiance availability mitigates the physiological performance of species of the calcifying green macroalga Halimeda in response to ocean acidification. Algal Research, 48: 101906. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2020.101906

|

|

Wei Zhangliang, Long Chao, Yang Fangfang, et al. 2020b. Effects of plant growth regulators on physiological performances of three calcifying green macroalgae Halimeda species (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta). Aquatic Botany, 161: 103186. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2019.103186

|

|

Wei Zhangliang, Mo Jiahao, Hu Qunju, et al. 2019. The physiological performance of the calcifying green macroalga Halimeda opuntia in response to ocean acidification with irradiance variability. Marine Science Bulletin, 38(5): 574–584

|

|

Wei Zhangliang, Zhang Yating, Yang Fangfang, et al. 2021. Increased light availability modulates carbon and nitrogen accumulation in the macroalga Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis (Rhodophyta) in response to ocean acidification. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 187: 104492. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104492

|

|

Wellburn A R. 1994. The Spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of Plant Physiology, 144(3): 307–313. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(11)81192-2

|

|

Wizemann A, Meyer F W, Hofmann L C, et al. 2015. Ocean acidification alters the calcareous microstructure of the green macro-alga Halimeda opuntia. Coral Reefs, 34(3): 941–954. doi: 10.1007/s00338-015-1288-9

|

|

Xiong Liming, Schumaker K S, Zhu Jiankang. 2002. Cell signaling during cold, drought, and salt stress. The Plant Cell, 14(S1): S165–S183

|

|

Yang Qing, Liu Qiyong, Bai Yan, et al. 2009. Responses of cholorophyll and soluble protein in different leaf layers of winter wheat to N and P nutrients. Journal of Triticeae Crops, 29(1): 128–133

|

|

Zeebe R E, Zachos J C, Caldeira K, et al. 2008. Oceans. Carbon emissions and acidification. Science, 321(5885): 51–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1159124

|

|

Zou Dinghui, Gao Kunshan. 2010. Photosynthetic acclimation to different light levels in the brown marine macroalga, Hizikia fusiformis (Sargassaceae, Phaeophyta). Journal of Applied Phycology, 22(4): 395–404. doi: 10.1007/s10811-009-9471-4

|

|

Zou Dinghui, Gao Kunshan. 2013. Thermal acclimation of respiration and photosynthesis in the marine macroalga Gracilaria lemaneiformis (Gracilariales, Rhodophyta). Journal of Phycology, 49(1): 61–68. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12009

|

| 1. | Chao Long, Yating Zhang, Zhangliang Wei, et al. High nutrient availability modulates photosynthetic performance and biochemical components of the economically important marine macroalga Kappaphycus alvarezii (Rhodophyta) in response to ocean acidification. Marine Environmental Research, 2024, 194: 106339. doi:10.1016/j.marenvres.2023.106339 | |

| 2. | Yating Zhang, Zhiliang Xiao, Zhangliang Wei, et al. Increased light intensity enhances photosynthesis and biochemical components of red macroalga of commercial importance, Kappaphycus alvarezii, in response to ocean acidification. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108465 |